Case Study: Salmonella Gastroenteritis in a 4-Month Old Infant

Alec A. Rudentein, MS3 Rowan SOM; Raveena K. Midha, MS3 Rowan SOM; Puthenmadam Radhakrishnan MD, MPH, FAAP

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella gastroenteritis is an infection that can result in serious and life-threatening complications in the pediatric population. Infants below the age of 12 months are especially at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Our case is a 4-month-old male who presents with gastroenteritis in the ED and evaluated for sepsis. Stool cultures were taken and resulted in a positive salmonella gastroenteritis diagnosis. Gastroenteritis is a common presentation in infants and is often not infectious in etiology.We present this case because it is imperative to acknowledge that salmonella infection is a potential and serious cause of gastroenteritis in infants. A search of literature resulted in many mentions of statistics and epidemiology; there are very scant case reports on Salmonella infections in infants.

CASE DESCRIPTION

This is a case of a 4-month-old male with no significant past medical history, born at full term who presented to the emergency department with reports of a fever and loose stools. Patient’s mother reported that onset of symptoms was 6 hours prior to presentation and temperature at home was 102.2 F.The patient had no sick contacts; no recent travel, no pets at home and all immunizations were up to date. Initial VS were significant for a rectal temperature of 105.9 and a HR of 200 BPM. Physical exam showed yellowish stools with streaks of blood, all other findings were unremarkable. Laboratory findings were significant for an elevated absolute neutrophil count (7.38×10^3/mcl), an elevated absolute lymphocyte count (0.72 x 10^3/mcl), and an elevated CRP (2.0 mg/dL). Urinalysis was normal and the patient was negative for influenza, COVID-19, and RSV. XR of chest/ abdomen showed no acute abnormalities. Patient was admitted to the pediatric in-patient floor for further evaluation and a stool culture was ordered.

On the pediatric floor, the patient was given acetaminophen and IV fluid for hydration. A sepsis evaluation including lumbar puncture with CSF cultures and blood cultures were performed on hospital day 2. Stool culture obtained were positive for Salmonella species. After a discussion with pediatric ID, it was decided that the patient would be placed on IV ceftriaxone. The patient’s diarrhea began decreasing on hospital day 5 and stools remained non-bloody for more than 24 hours. Blood culture and CSF cultures showed no growth after 2 days. Patient’s intake increased to 4 oz of fullstrength formula every 4 hrs. After the patient was afebrile for approximately 36 hours, he was discharged on hospital day 6 and placed on azithromycin PO for a duration of 5 days.

Salmonella is a motile, gram-negative facultative anaerobic bacilli as part of the Enterobacteriaceae family.There are numerous Salmonella serotypes and species; however, this case focuses on non-typhoidal Salmonella species and their particular deleterious effects in infants. Most non-typhoidal Salmonella infections are acquired through food-borne contaminants. Frequent transmission of non-typhoid Salmonella infections occurs due to the consumption of contaminated animal-based food, such as eggs, meat, dairy products, contaminated water, or poor hygiene [3]. The infections can be self-limiting or progress to more advanced states. In addition, formula is also a potential nidus for Salmonella infection. The improper storage of formula is the most likely cause of formula-caused Salmonella infection [3]. Furthermore, Salmonella , unlike many other enteric pathogens, have an asymptomatic carrier state which can help spread the disease. A common way for the pathogen to spread to newborns and children is through maternal asymptomatic carriers [1,3].

In the case presented, it was thought that the patient was exposed to Salmonella via mishandling of poultry or an asymptomatic carrier.As there was no local outbreak of Salmonella from the formula, the Department of Health decided not to pursue the formula avenue. Likewise, the patient had no recent travel, no sick contacts and no pets at home.The patient’s mother cooks meals for the family so it can be speculated that the pathogen spread from the food to the mother to the patient.

Salmonella causes its effects locally within the gastrointestinal site as well as distantly through its ability to invade the intestinal mucosa and replicate within the lamina propria. From there, it can invade the mesenteric lymph nodes and spread to the rest of the body. Salmonella gastroenteritis is commonly associated with diarrhea, first starting with watery diarrhea and possibly progressing to bloody or mucus-containing diarrhea due to its invasive properties [1,3]. In immunocompetent adults, Salmonella gastroenteritis is eliminated through the body’s immune response, the naturally occurring enteric flora, gastric acid, and motility, as well as the intestinal mucus. Each aspect works to remove the pathogen as well as form protective barriers to prevent the organism from acclimating to the host’s internal environment. Infants and children lack or have an immature defense system and are thus at increased risk of developing more serious complications of Salmonella infections [1,4].

Noting Salmonella as the cause of gastroenteritis is imperative due to the systemic effects the organism can have. “Bacteremia may occur in 30-50% of neonates infected with Salmonella , including those with no evidence of gastroenteritis. Focal infections of almost every organ system (for example bone, joint, lung) are reported with Salmonella gastroenteritis, but meningitis is the most feared of these complications and emphasizes the vigilance required to evaluate infants who are infected with Salmonella ” [1].The peak incidence of Salmonella bacteremia and meningitis occur in infants less than 2 months of age [2]. According to the CDC, infants, especially those who are not breastfed or have a weakened immune system, are more likely to get an invasive Salmonella infection and should be treated with antibiotics [3,4].

It is recommended that the use of antibiotics be limited in immunocompetent individuals aged 12 months to 50 years old with acute salmonella gastroenteritis because of the self-limiting course of disease. It is established that patient’s less than 3 months of age are given antibiotics due to a risk of complications such as sepsis and meningitis [9]. However, there is little evidence to support that antibiotics should be given from 3 months to 12 months of age. According to a review of literature in 2017, the current recommended guidelines for a patient between 3 months-12 months of age is no treatment required if the patient appears well and non-toxic. If the patient is unwell or toxic appearing, then blood culture, with or without CSF culture, should be obtained and parenteral antibiotics should be started. If the blood culture shows no growth at 48 hours and the patient appears well, then the patient can be switched to oral antibiotics [6]. Antibiotic therapy duration for immunocompetent children is recommended at 3-14 days [5]. According to these guidelines, it was necessary to place our patient on antibiotic therapy due to multiple bouts of bloody diarrhea and persistently high fever, dehydration and general ill appearance.

The mainstay treatment of Salmonella gastroenteritis for adults and adolescents is an oral dose of fluoroquinolones because of their antimicrobial activity against gram-negative enteric pathogens. Some data has shown that fluoroquinolones could potentially be safe during short courses of antibiotics for children. However, previous data on animal models suggests that fluoroquinolones can cause joint toxicity and cartilage damage. As a result, they are not typically prescribed in children [8]. Alternatives to fluoroquinolones are other oral antibiotics such as TMP-SMX, cefixime and azithromycin. Due to this patient’s poor oral intake and peripheral IV access, IV ceftriaxone was a reasonable choice of antimicrobial therapy. Ceftriaxone has been shown to be as effective as oral ciprofloxacin in children with acute invasive diarrheas [ 7]. In addition, ceftriaxone eliminates the risk of joint toxicity in vulnerable pediatric patients such as this 4-month-old male. In this case, the duration of parenteral antibiotic therapy was 3 days. Following discharge, the patient was prescribed azithromycin for 5 additional days for a total of 7 days which falls in the recommended guidelines discussed above.

Gastroenteritis in infants, particularly children under 12 months of age, is a common condition with a range of causes. In many cases, the illness is self-limited and no antibiotics or treatments are needed. However, it is important to note that Salmonella is also a common cause of gastroenteritis and should always be included in the differential diagnosis. In the case presented, the patient was brought to the ED for a sepsis workup and it was most likely due to the presentation of bloody stools that the stool culture was ordered. However, Salmonella’s presentation can vary from watery stools to asymptomatic infections.Though the clinical presentations differ, Salmonella’s potential systematic effects can prove to be fatal. Therefore, Salmonella gastroenteritis should be considered in the differential diagnosis due to its ability to invade the lymphatic system and spread to cause more systemic infections.

- Kinney JS, Eiden JJ. Enteric infectious disease in neonates. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and a practical approach to evaluation and therapy. Clin Perinatol. 1994 Jun;21(2):317- 33. doi: 10.1016/S0095-5108(18)30348-8. PMID: 8070229; PMCID: PMC7133246.

- Nelson SJ, Granoff D. Salmonella gastroenteritis in the first three months of life. A review of management and complications. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1982 Dec;21(12):709-12. doi: 10.1177/000992288202101201. PMID: 7140121.

- Bula-Rudas FJ, Rathore MH, Maraqa NF. Salmonella Infections in Childhood. Adv Pediatr. 2015 Aug;62(1):29-58. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2015.04.005. PMID: 26205108.

- “Questions and Answers.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5 Dec. 2019, www.cdc.gov/salmonella/general/index.html.

- Sirinavin, S, and P Garner. “Antibiotics for Treating Salmonella Gut Infections.” Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2 (2000): CD001167–CD001167. Print.

- Wen, Sophie CH, Emma Best, and Clare Nourse. “Non- Typhoidal Salmonella Infections in Children: Review of Literature and Recommendations for Management: Non- Typhoidal Salmonella Infections.” Journal of paediatrics and child health 53.10 (2017): 936–941.Web.

- LEIBOVITZ, EUGENE et al. “Oral Ciprofloxacin Vs. Intramuscular Ceftriaxone as Empiric Treatment of Acute Invasive Diarrhea in Children.” The Pediatric infectious disease journal 19.11 (2000): 1060–1067.Web.

- GRADY, RICHARD. “Safety Profile of Quinolone Antibiotics in the Pediatric Population.” The Pediatric infectious disease journal 22.12 (2003): 1128–1132.Web.

- ST. GEME, JOSEPH W et al. “Consensus: Management of Salmonella Infection in the FirstYear of Life.”The Pediatric infectious disease journal 7.9 (1988): 615–621.Web.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella infection with multifocal seeding in an immunocompetent host: an emerging disease in the developed world

Rebecca louise hall, rebecca partridge, navin venkatraman, martin wiselka.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to Rebecca Louise Hall, [email protected]

Series information

Case Report

Collection date 2013.

We report an immunocompetent 24-year-old man who presented with a severe, invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS) infection. He presented with lumbar back pain associated with fever and rigours, which had been preceded by diarrhoea. Blood cultures grew Salmonella enteritidis . An MRI scan of his pelvis and spine showed that he had a small gluteal abscess and sacroiliitis. His condition subsequently deteriorated due to the development of a secondary pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was managed conservatively with 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone, followed by 6 weeks of oral ciprofloxacin. Detailed investigations did not reveal any predisposing factors or evidence of an underlying immunodeficiency. Follow-up showed complete resolution of symptoms with no long-term sequelae.

This case is important for a number of reasons. Globally, invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS) infection is increasing and has emerged as one of the leading causes of morbidity and deaths in sub-Saharan Africa. 1 We describe a case of iNTS infection with multi-organ involvement, which is extremely rare in the developed world. Furthermore, most patients have an underlying immunodeficiency or predisposing condition. 2 This was not the case in our patient, thus making it a very unique presentation. To our knowledge, invasive Salmonella enteritidis infection in an immunocompetent host, resulting in a gluteal abscess and sacroiliitis complicated by pneumonia, has not been reported previously.

Case presentation

A previously fit and healthy 24-year-old Caucasian man presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of severe lumbar back pain radiating into the right buttock and lower limb, rendering him unable to walk. He also complained of fever and rigours, associated with a generalised headache and vomiting. The patient had been suffering with 7 days of bloody diarrhoea, which had ceased 2 days prior to admission. There was no significant medical history or relevant risk factors for infection, such as travel and pets. He was not on any regular medication and did not report any allergies. He did not smoke or drink any alcohol. There was no significant family history.

His initial observations were as follows: pulse 92 beats/min, blood pressure 101/50 mm Hg, temperature 39.2°C, saturations 96% on air and respiratory rate 22/min. He was fully conscious with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15 and a blood sugar of 6.9 mmol/l. Initial examination elicited severe pain in the right buttock on palpation. There were no rashes or signs of meningism. The remainder of his examination, including neurological examination, was unremarkable.

He was transferred to the acute medical unit and was initially managed with intravenous fluids. He underwent investigations for a presumptive diagnosis of discitis with blood cultures and an MRI spine. The following day, he was started on intravenous co-amoxiclav as a Gram-negative organism had been identified in his blood culture. An ultrasound showed an ill-defined region within the right gluteus maximus; an MRI of the pelvis was suggested for further characterisation.

He was subsequently transferred to a medical ward, where he was noted to be significantly hypoxic and persistently febrile by the nursing staff. He was started on oxygen and the doctors were informed. At this stage, it became apparent that he was growing S enteritidis in his blood cultures and his antibiotic was therefore changed to ceftriaxone. Unfortunately, his clinical condition deteriorated rapidly over the following hours and he became profoundly septic, hypoxic and had a significant metabolic acidosis. He was peripherally shut down and mildly icteric. His observations showed cardiorespiratory compromise ( table 1 ) and auscultation of the chest revealed fine bibasal crackles. A chest x-ray showed left lower lobe consolidation. Other observations are shown in table 1 .

Observations for the patient on the day of admission compared with day 4

Dissemination of this pathogen, which is usually localised to the gut, brought into question whether he was immunocompromised. At this point, the patient was transferred to the infectious disease unit.

Investigations

Routine blood tests showed the following results:

The remainder of his blood, including urea, creatine and electrolytes, was all normal.

Investigations for immunodeficiency

HIV antibody/antigen test: negative×2.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis: normal.

Lymphocyte profile showed normal numbers of T cells, natural killer cells and polyclonal B cells in his peripheral blood and a normal neutrophil oxidative burst, which excluded chronic granulomatous disease.

There was no evidence of type I cytokine deficiency—normal interferon-γ and interleukin 12 (IL-12) pathways.

Microbiology

Blood cultures×2: grew S enteritidis phage type 56.

Sensitivity to: ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime/ceftriaxone, azithromycin.

E test: ciprofloxacin 0.016 mg/l, azithromycin 2 mg/l.

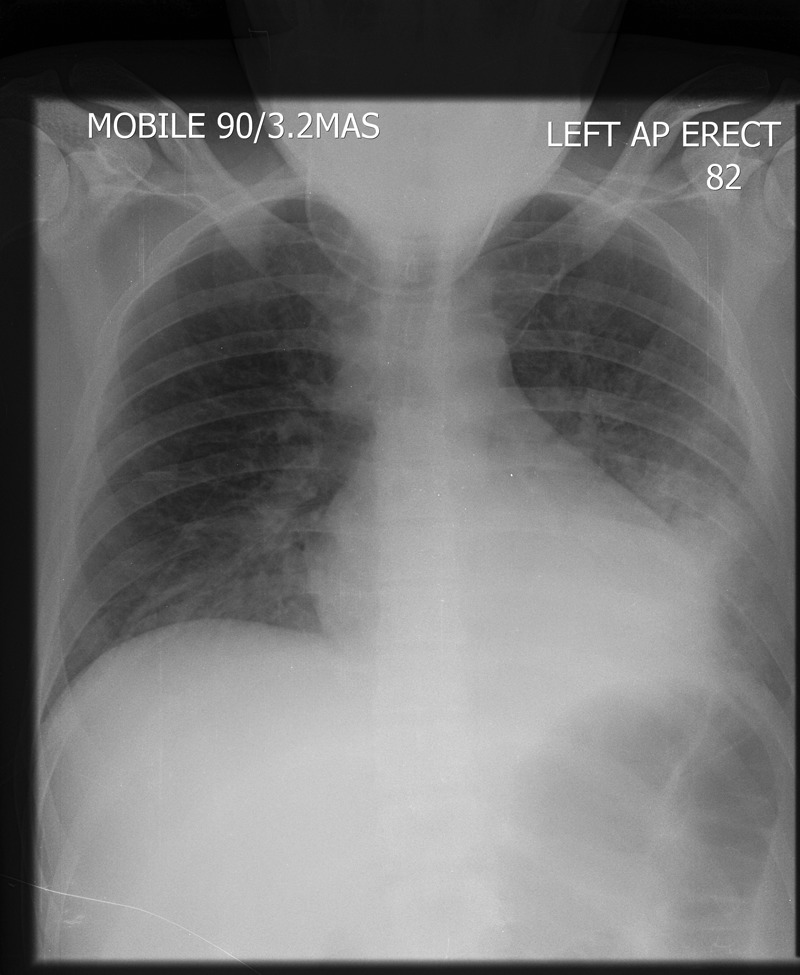

Admission: normal chest x-ray ( figure 1 ) and normal MRI spine.

Admission chest x-ray showing clear lung fields.

Ultrasound pelvis: A 2.8 cm×2 cm ill-defined region within the right gluteus maximus muscle.

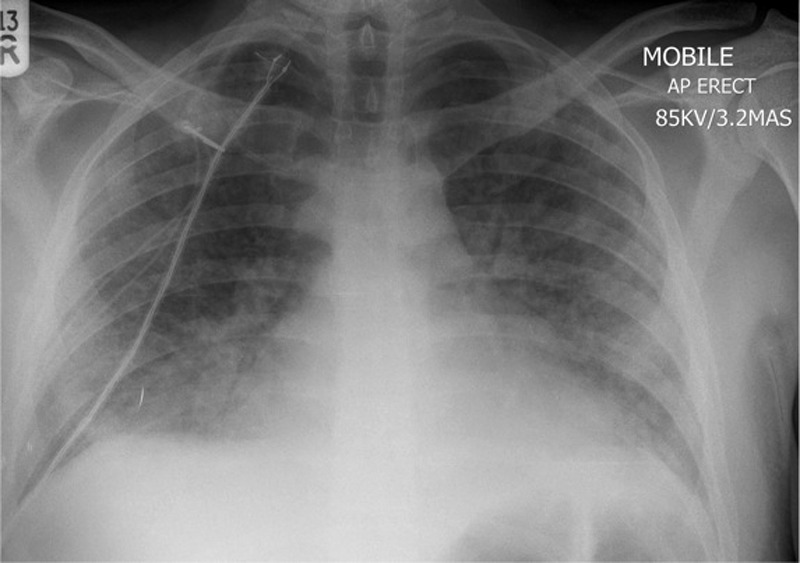

Day 3: chest x-ray showed left lower lobe consolidation ( figure 2 ).

A portable chest x-ray (day 3) showing a new left lower lobe consolidation.

Day 6: a repeated chest x-ray showing progressive bilateral interstitial changes ( figure 3 ).

A portable chest x-ray (day 6) showing bilateral interstitial shadowing consistent with worsening of infection or an acute respiratory distress syndrome picture.

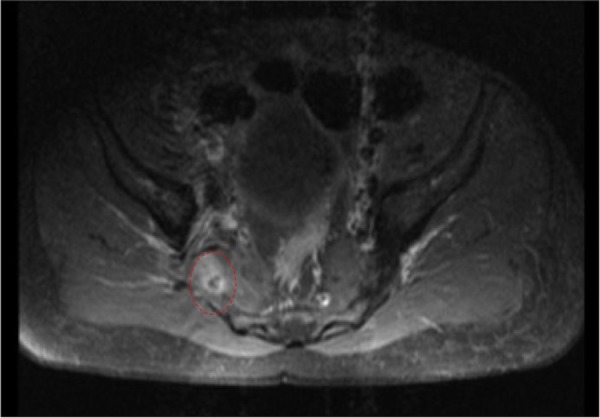

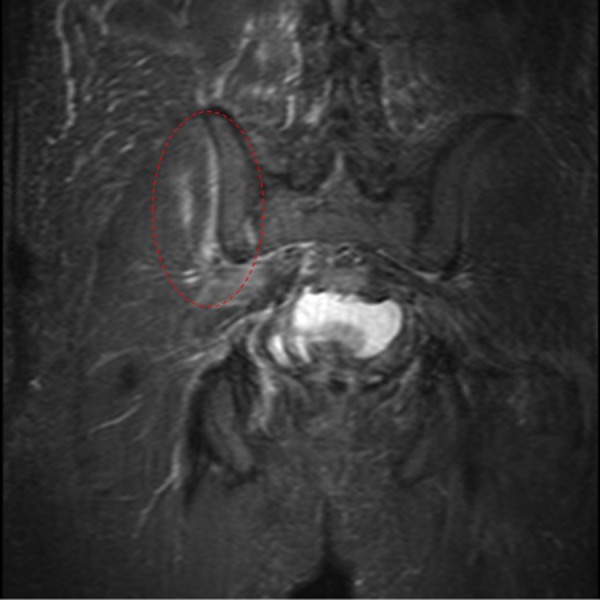

Day 6: an MRI of the pelvis with contrast showed a small gluteal abscess inferior to the right sacroiliac joint (SIJ) ( figure 4 ). A right SIJ effusion with surrounding bone marrow oedema was also demonstrated ( figure 5 ).

MRI of the pelvis showing a small right gluteal abscess with surrounding oedema.

MRI of the pelvis showing the right sacroiliac joint effusion with surrounding bone marrow oedema.

A repeated chest x-ray was performed on day 12 of his admission and demonstrated clear lung fields.

Differential diagnosis

Gastroenteritis

Septic arthritis

Osteomyelitis

Initially, the patient was treated with co-amoxiclav, which was started on day 2. On day 3, blood cultures grew S. enteritidis . He was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for 14 days. His acute respiratory deterioration was managed with high-flow oxygen and close supervision of the critical care outreach team. He was initially quite difficult to wean off the oxygen, and a repeated chest x-ray showed progressive interstitial changes bilaterally, which could have been representative of worsening infection or acute respiratory distress syndrome. The orthopaedic team reviewed his case and decided that surgical drainage would be difficult given the location, so systemic antibiotic therapy was continued. By day 8, the patient appeared to be improving clinically with decreasing oxygen requirements and his temperature was settling. After completing 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone, he continued taking oral ciprofloxacin for another 6 weeks to ensure absolute eradication of the organism.

Outcome and follow-up

On discharge, 15 days after admission, he still had pain in his buttocks with reduced mobility requiring crutches and physiotherapy. He had no fever, and oxygen saturations were 100% on air. He was discharged on oral antibiotics and continued a 4-week follow-up appointment in the infectious disease clinic. When seen in the clinic, he had fully recovered and was back at work. His inflammatory markers had all returned to normal. Extensive investigations by the immunologists for evidence of inherited immunodeficiencies did not reveal any abnormalities. At this point, he was discharged from our care with no long-term sequelae.

The patient believed that he contracted the infection from a chicken burger he had consumed in a fast food restaurant, prior to his illness. The infection was notified to the Health Protection Agency (HPA).

Salmonellae are Gram-negative bacilli that cause a number of clinical manifestations in humans. Non-typhoidal salmonellae (NTS), including S. enteritidis , Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella newport , are a very common cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. S. enteritidis is most often a foodborne infection associated with poorly prepared or raw eggs and poultry. It can also be contracted from pet animals and contaminated pet food. 3 The iNTS infection has emerged as an important cause of bacteraemia and significant mortality worldwide. It is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the most common isolates from febrile patients, both in adults and children. 4 In high-income countries, NTS usually cause a self-limiting diarrhoeal illness, with a small proportion developing bacteraemia and extra-intestinal focal infections.

The International Bacteraemia Surveillance Collaborative recently reported the first population-based incidence of iNTS infection in the developed world. 5 They documented cases between 2000 and 2007 in Finland, Australia, Denmark and Canada. They reported a crude annual incidence of 0.81/100 000. Interestingly, they also showed a gradual increase in the incidence of iNTS infection over the period of the study. At present, there are no similar data available for the UK, even though the HPA publishes figures for the overall incidence of NTS infections. In 2010,HPA reported 2444 cases of S. enteritidis infection in UK and Wales, which has shown a downward trend in incidence over the past decade. 6

A recent review from Cambridge, UK documented over 1000 cases of salmonella infections presenting to their hospital over a 10-year period. 7 However, they only reported 21 cases of iNTS infection, and 14 of these cases had an underlying immunosuppression or presented at extremes of age (10 years>age>80 years).

Using PubMed, we reviewed over 50 case reports of invasive S enteritidis infection with focal seeding resulting in infections at multiple locations. It has been reported to cause musculoskeletal, central nervous system, pulmonary, cardiovascular and urinary infections. 8–10 Nearly all the cases presented in patients at the extremes of age or had underlying predisposing factors. Factors included sickle cell disease, immunosuppression, malignancies, immunomodulating therapy and systemic lupus erythematosus. 11–13 One case documented septicaemia associated with IL-12 receptor deficiency; testing in our patient showed an appropriate response to IL-12. 14 A Spanish study detailed 35 invasive salmonella infections presenting to their hospital over a 10-year period. 8 They reported infections involving numerous sites, including four cases of pulmonary infection and three cases of bone infection. All of these seven cases had predisposing factors apart from one 16-year-old girl who had an evidence of sacroiliitis and cultured S enteritidis from her urine. Two of the pulmonary cases died and had underlying malignancy. Knight et al 15 reported two cases of pulmonary NTS infections; however, both patients had undiagnosed type II diabetes mellitus. Schmidt et al 16 reported a case of Salmonella choleraesuis sacroiliitis in a 17-year-old school boy. Aligeti et al 17 reported a case of S typhimurium gluteal abscess in the absence of risk factors for salmonellosis.

Our patient was a previously healthy 24-year-old man who presented with S enteritidis bacteraemia, complicated by a gluteal abscess and associated sacroiliitis. His condition deteriorated significantly on day 3 of his admission due to a left lower lobe pneumonia causing respiratory failure. It is impossible to be certain whether this was due to seeding of his salmonella bacteraemia or a healthcare-associated pneumonia (HAP). However, it was very early on in the course of his illness and he was on appropriate intravenous antibiotics to cover HAP. Unfortunately, we did not obtain any positive cultures from respiratory samples to definitely prove this. To our knowledge, there are no similar published cases on immunocompetent hosts in the English literature.

The fluoroquinolones and the third-generation cephalosporins are appropriate antibiotic choices for the management of iNTS infections. 18 Extraintestinal infection often requires surgical debridement; however, the orthopaedic surgeons deemed that his abscess was too small to warrant drainage. We, therefore, opted for prolonged antibiotics to successfully treat his infection. The optimal length of treatment is dependent on the patient's immune status and the site of infection. A minimum of 3 weeks’ therapy is recommended, and our patient was treated with a total of an 8-week course of antibiotics. The emergence of resistance to these antibiotics has been reported in NTS infection. 19 20 Our patient was fully susceptible to the fluoroquinolones ( minimum inhibitory concentration, 0.016 mg/l) and third-generation cephalosporins.

Barrier nursing and hand washing are important to prevent onward transmission, and NTS bacteraemia is a notifiable disease. In addition to antimicrobial therapy, the detection of an iNTS infection should prompt a thorough search for immunodeficiency or predisposing factors including HIV testing, sickle cell screen, T-lymphocyte and cytokine profile testing. In our patient, there was no evidence of any predisposing factors. At follow-up, he was completely asymptomatic and had no evidence of long-term sequelae.

In summary, we present a unique case of iNTS infection with multi-focal seeding in an immunocompetent host. This condition, which has emerged as one of the most important diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, is likely to assume increasing importance in the developed world.

Learning points.

How unusual is it for Salmonella enteritidis septicaemia to present in a young, seemingly immunocompetent patient?

The location of other foci of infection in this presentation, that is, the lung, sacroiliac joint and the pelvis.

The investigation and management of an acutely unwell patient from admission to transfer to other wards.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 2012;379:2489–99 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Dhanoa A, Fatt Q. Non-typhoidal salmonella bacteraemia: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and its’ association with severe immunosuppression. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2009;8:15. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Hohmann EL.2012. Microbiology and epidemiology of salmonellosis. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/microbiology-and-epidemiology-of-salmonellosis?source=search_result&search=nontyphoidal+salmonella&selectedTitle=3~15 (accessed 14 Aug 2012)

- 4. Morpeth SC, Ramadhani HO, Crump JA. Invasive non-typhi salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:606–11 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Laupland KB, Schonheyder HC, Kennedy KJ, et al. Salmonella enterica bacteraemia: a multi-national population-based cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:95. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Health Protection Agency Salmonella by serotype: epidemiological data on all human isolates reported to the heath protection agency centre for infections England and wales 2000–2010. 2011. http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/Salmonella/EpidemiologicalData/salmDataHuman/ (accessed 20 July 2012)

- 7. Matheson N, Kingsley RA, Sturgess K, et al. Ten years experience of salmonella infections in Cambridge, UK. J Infect 2010;60:21–5 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Munigangaiah S, Khan H, Fleming P, et al. Septic arthritis of the adult ankle joint secondary to salmonella enteritidis: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011;50:593–4 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Rodriguez M, de Diego I, Martinez N, et al. Nontyphoidal salmonella causing focal infections in patients admitted at a Spanish general hospital during an 11-year period (1991–2001). Int J Med Microbiol 2006;296:211–22 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Samonis G, Maraki S, Kouroussis C, et al. Salmonella enterica pneumonia in a patient with lung cancer. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:5820–2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. El-Herte RI, Haidar RK, Uthman IW, et al. Salmonella enteritidis bacteremia with septic arthritis of the sacroiliac joint in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban 2011;59:235–7 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Stein M, Houston S, Pozniak A, et al. HIV infection and salmonella septic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1993;11:187–9 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Henderson RC, Rosenstein BD. Salmonella septic and aseptic arthritis in sickle-cell disease. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;248:261–4 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Carvalho BT, Iazzetti AV, Ferrarini MA, et al. Salmonella septicemia associated with interleukin 12 receptor beta1 (IL-12Rbeta1) deficiency. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2003;79:273–6 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Knight JC, Knight M, Smith MJ. Two cases of pulmonary complications associated with a recently recognised salmonella enteritidis phage type, 21b, affecting immunocompetent adults. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000;19:725–6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Schmidt DB, Meier R, Ochsner PE, et al. Acute bacterial sacroiliitis caused by salmonella choleraesuis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1988;113:1474–7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Aligeti VR, Brewer SC, Khouzam RN, et al. . Primary gluteal abscess due to salmonella typhimurium: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2007;333:128–30 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Hohmann EL.2012. Nontyphoidal salmonella bacteremia. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/nontyphoidal-salmonella-bacteremia?source=search_result&search=nontyphoidal+salmonella&selectedTitle=1~15 (accessed 14 Aug 2012)

- 19. Stevenson JE, Gay K, Barrett TJ, et al. Increase in nalidixic acid resistance among non-typhi salmonella enterica isolates in the United States from 1996 to 2003. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:195–7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Lee HY, Su LH, Tsai MH, et al. High rate of reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone among nontyphoid salmonella clinical isolates in Asia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:2696–9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (277.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices.

Date last reviewed: 5/28/2008

American Society for Microbiology

- Case Studies

- Salmonella gastroenteritis Lab Testing and Treatment

Case Studies Salmonella gastroenteritis Lab Testing and Treatment

March 27, 2019

Download the Case Study

Presentation

Lab testing, cause of symptoms, contact information.

Nicole Jackson, [email protected]

Last Chance to Register for the 2024 ASM NGS Conference

Discover asm membership, get published in an asm journal.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 05 April 2022

Case report: post-salmonellosis abscess positive for Salmonella Oranienburg

- Brenda M. Castlemain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4739-8939 1 &

- Brian D. Castlemain 2

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 22 , Article number: 337 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

1813 Accesses

Metrics details

Salmonella gastroenteritis is a self-limited infection in immunocompetent adults. Salmonella Oranienburg is a serovar that has recently caused outbreaks of gastroenteritis traced to contact with a pet turtle. Extraintestinal focal infections (EFIs) with invasive Salmonella have been reported uncommonly, examples of which include mycotic aneurysm and spinal osteomyelitis.

Case presentation

The patient is an otherwise healthy 39-year-old male with sleep apnea presenting with pain and swelling in the left anterior chest wall several months after an episode of Salmonella gastroenteritis and bacteremia which was treated successfully with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. He was found to have a costochondral joint abscess with operative cultures positive for S. Oranienburg , a serovar reported to have been associated with pet turtles and onions in recent CDC and FDA news releases. Of note, the joint abscess began development 2–3 months after his episode of Salmonella bacteremia. At the time of surgical treatment, nearly 6 months had passed since the initial episode of gastroenteritis and bacteremia.

Conclusions

Delayed development of a sternocostal joint abscess after Salmonella bacteremia in an otherwise healthy adult male is an unusual presentation. The patient had two different exposures: a fast food chicken lunch and a pet turtle at home. Extraintestinal focal infections with invasive Salmonella are very uncommonly reported in healthy adult patients treated in developed countries. To our knowledge, we report this sequala for the first time.

Peer Review reports

Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) infection generally results in a self-limited diarrheal disease in immunocompetent patients. Invasive disease (iNTS) is uncommon in developed countries but is highly reported in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. It is estimated that about 3.4 million cases of iNTS occur annually with around 681,316 deaths, 2/3 of which are children under the age of 5 [ 1 ]. Salmonella bacteremia is rare in immunocompetent patients, with an estimated 5% of patients developing this complication [ 2 , 3 ]. Extraintestinal Salmonella infection is even more uncommon, though several cases have been reported- the majority in children or immunocompromised adults [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. The development of a retroperitoneal abscess in a pediatric patient has been reported and speculated to have been the result of Salmonella penetration of the intestinal wall and lymphatic travel to the retroperitoneal nodes [ 5 ]. Here we describe a Salmonella infected sternocostal joint abscess that began development 2–3 months after Salmonella gastroenteritis treated successfully with intravenous antibiotics in an otherwise healthy patient.

The patient is a 39-year-old male with medical history of obstructive sleep apnea who presented in February of 2021 with progressive left anterior chest wall pain and a fluctuant mass in that region. The patient, who had a pet turtle at home, developed crampy abdominal pain and diarrhea about 12 h after eating a fast-food chicken meal in September 2020. Within a week of that episode, he was admitted at a local hospital with fever and chills and admitted to be treated for Salmonella Oranienburg sepsis. Sensitivities were found to be to ampicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. He was treated with a 5-day course of IV levofloxacin and metronidazole, then a 10-day course of twice-daily ciprofloxacin. He recovered, but in November of 2020, he noticed progressive discomfort in the left anterior chest wall with point tenderness in the region of the fourth sternocostal joint. Anti-inflammatory medications reportedly kept the pain manageable, but he noted a gradually increasing firm but fluctuant lump in that area.

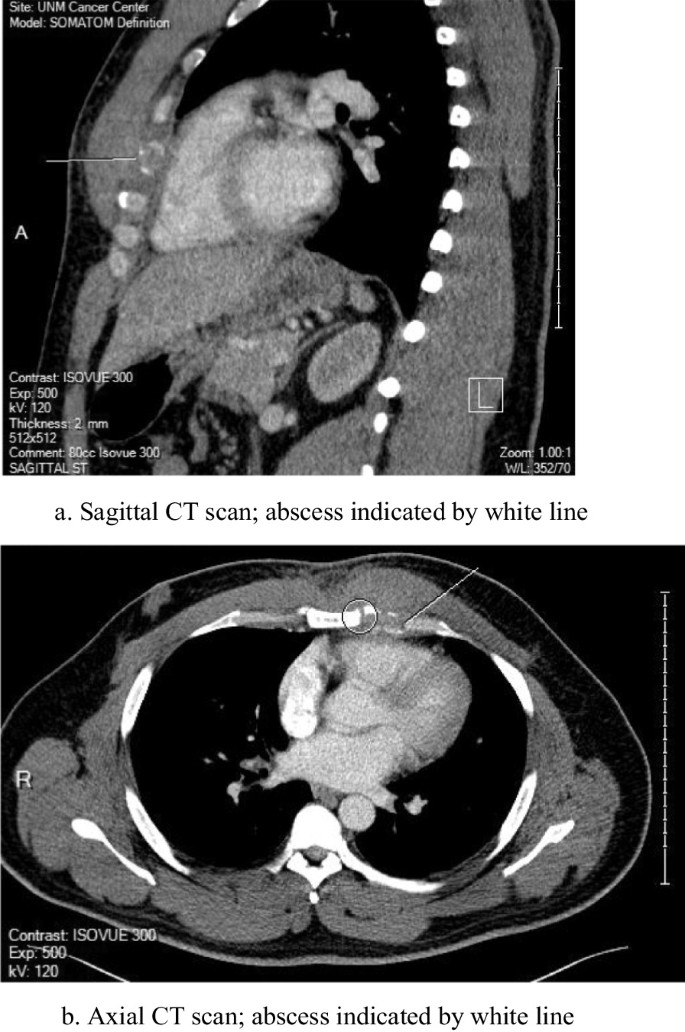

A CT scan of the chest was performed (Fig. 1 a and b) and the patient was referred to the cardiothoracic surgery service for evaluation. Needle aspirate of the area failed to reveal a bacterial source or other histological abnormality, and the patient was taken to the operating room for exploration. At operation, a small discrete purulent collection was noted deep to the fourth sternocostal joint and wide debridement was undertaken with wound vac placement. Operative cultures revealed S. Oranienburg . Sensitivities for this isolate included ampicillin, ceftriaxone and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. These isolates were not genetically compared to the blood sample taken from the bacteremia episode. The patient received IV ceftriaxone through a peripheral line for 6 weeks following his surgery. The wound closed within a month, and the patient made a full recovery several months after his surgery. Of note, the patient did not have positive stool cultures at any point during his illness.

a Sagittal CT scan; abscess indicated by white line. b Axial CT scan; abscess indicated by white line

Despite advances in individual and community-based sanitation, salmonellosis remains an endemic problem in most industrialized countries. The CDC estimates Salmonella cases at 1.35 million a year in the United States. Among those cases, there are 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths [ 9 ]. Food is the source of infection in the majority of those cases. Eggs and poultry seem to be the more common food vectors, but most contaminated food items can become transmission agents.

The CDC has investigated multiple Salmonella outbreaks in the United States in which contact with a turtle was a common exposure [ 9 ]. In fact, small pet turtles are reported by the CDC as the source of a Salmonella outbreak every year for the past 5 years. [ 10 ] The 2019 pet turtle outbreak identified Salmonella Oranienburg as the culprit serovar [ 10 , 11 ]. A recent outbreak concluding in October of 2021 was traced to onions from a single farm in Mexico and Salmonella Oranienburg was identified as the source of outbreak [ 12 , 13 ]. Other sources of recent outbreak include salami sticks, Italian-styled meats, seafood and pre-packaged salads.

Salmonella infection most commonly presents as a gastroenteritis, but subacute and remote sequelae have a vast array of presentations. Immunocompromised individuals may be at increased risk for serious initial infection and long-term sequelae. Also at risk are patients in developing countries where sanitation measures and healthcare access are limited, posing barriers to effective antibiotic treatment. Extraintestinal focal infections (EFI) of NTS have been reported uncommonly with unclear risk factors. Several examples of EFIs include mycotic aneurysm, pleuropulmonary infection and spinal osteomyelitis [ 2 ]. A Salmonella Enteritidis infected sternal abscess was reported in a healthy 6-year-old, but this patient had no gastrointestinal symptoms before or during their disease course [ 14 ].

The case reported here is notable for several reasons. To begin, the patient is a young and healthy individual with no known history of gastrointestinal disease. His invasive infection with Salmonella was treated with a full course of antibiotics and the patient had negative blood cultures upon discharge. His chest wall discomfort did not begin until 2–3 months after completion of his antibiotic therapy. By the time he underwent surgical debridement, nearly 6 months had passed since his initial presentation with Salmonella bacteremia. We speculate that a small focus of bacteria seeded the costochondral joint space during initial infection and grew slowly in the low-oxygen environment. However, the time course is befuddling, and to our knowledge, a novel presentation. Although the pet turtle exposure is likely coincidental, we acknowledge here the relationship between Salmonella Oranienburg and small shelled reptiles. The pet turtle was not tested for Salmonella and could be a source of reinfection.

The patient in our study consumed a fast-food chicken meal 1 week prior to the onset of his gastrointestinal symptoms. Although this exposure was most likely the vector, other sources of infection must be considered . Salmonella was found to be present in 80% of water samples taken from the rivers of Culiacan Valley in Northwestern Mexico, with Salmonella Oranienburg being the most frequently isolated serotype [ 15 ]. The patient in our study resides in Alamogordo, New Mexico, home to the Tularosa basin of the Rio Grande river. While E Coli has been identified as the most prominent bacterium in Rio Grande waters, Salmonella contamination forces, such as agriculture and human waste, can be at play in any large body of water [ 16 ]. It is certainly a possibility that the patient in our case encountered a waterborne source of contamination. Other contaminated food items could have caused the infection. Although less likely, physical contact with the pet turtle without proper hand washing could also have introduced the bacterium.

In searching the literature, we encountered very few cases describing extraintestinal focal infections with Salmonella occurring in a developed hospital setting in a young, healthy adult individual without comorbid health conditions. A case out of Australia described a young, healthy individual with hemorrhagic cystitis caused by S. Oranienburg, with exposure likely resulting from Salmonella gastroenteritis from an extended trip to South America. Of note, the spread from the gastrointestinal to genitourinary system, particularly in the case of profuse diarrhea, is not uncommon [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Similarly, another case reports the development of an S . Oranienburg positive renal abscess an immunocompetent child in Taiwan. Again, this child was reported to have gastrointestinal symptoms 1 week prior to increasingly severe flank pain and fever, indicating that Salmonella gastroenteritis resulting in ascending genitourinary tract was likely the source of infection [ 20 ]. Our case describes a route of spread that cannot be traced with such ease. In addition, the prolonged period between initial infection with Salmonella and the appearance of a costochondral mass suggests that the two episodes could possibly be unrelated.

This study is limited by our need to speculate—we are unsure of the pathogenesis of the abscess described and can only formulate a hypothesis. The study is also limited by the extended period of time between the initial presentation with gastroenteritis and the described presentation with chest wall discomfort. We are not privy to any extraneous risk factors the patient may have encountered. For example, the patient may have been scratched by his pet turtle unknowingly, thus inoculating the skin with bacteria. The patient reported minimal contact with the turtle, but we cannot be certain. With recent news releases detailing outbreaks of Salmonella Oranienburg, we believe our case report is timely and relevant.

Our patient is a healthy 39-year-old male without significant medical illness or ongoing conditions that would have contributed to his infection. His family did have a pet turtle with which he had minimal contact. The inciting event which exposed him to the bacteria seems to have been eating chicken at a fast-food restaurant from which he developed gastroenteritis-like symptoms shortly thereafter. Of note, an interesting sequela of our patient’s infection was his development of a sternocostal joint abscess 2 or 3 months after his initial bout of infection. To our knowledge, we report this particular sequela here for the very first time. He was apparently asymptomatic from the time of his initial infection to the time period where he developed the somewhat fluctuant mass up his chest wall. The infection was treated with open debridement and IV antibiotics. The patient made a full recovery and is infection-free and doing well over a year from his initial infection.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

Extraintestinal focal infections

Intravenous

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

Food and drug administration

Non-typhoidal Salmonella

Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella

Computed tomography

Balasubramanian R, Im J, Lee JS, Jeon HJ, Mogeni OD, Kim JH, Rakotozandrindrainy R, Baker S, Marks F. The global burden and epidemiology of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(6):1421–6.

Article Google Scholar

Chen PL, Chang CJ, Wu CJ. Extraintestinal focal Infectious in adults with nontyphoid Salmonella bacteremia: predisposing factors and clinical outcome. J Intern Med. 2007;261(1):91–100.

Subburaju N, Sankar J, Putlibai S. Non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteremia. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85(9):800–2.

Altaf A, Tunio N, Tunio S, Zafar MR, Bajwa N. Salmonella urinary tract infection and bacteremia following non-typhoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis: an unusual presentation. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12194.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Katsuno S, Ando H, Seo T, Shinohara T, Ochiai K, Ohta M. A case of retroperitoneal abscess caused by Salmonella Oranienburg. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(11):1693–5.

Thomas GC. Salmonella . Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (ed 16). Philadelphia, PA, Saunders, 2000, pp 842–845.

Banky JP, Ostergaard L, Spelman D. Chronic relapsing Salmonella osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent patient: case report and literature review. J Infect. 2002;44:44–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Picillo U, Italian G, Marcialis MR, et al. Bilateral femoral osteomyelitis with knee arthritis due to Salmonella enteritidis in a Patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:53–6.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Salmonella . Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated date August 21, 2021. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/Salmonella/index.html .

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Salmonella Infections linked to Pet Turtles. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated date January 9, 2020. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/Salmonella/oranienburg-10-19/index.html .

Food and Drug Administration. Pet Turtles: Cute but Commonly Contaminated with Salmonella . Food and Drug Administration. Updated February 2, 2021. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/pet-turtles-cute-commonly-contaminatedSalmonella#:~:text=These%20four%20outbreaks%20were%20traced,they%20had%20to%20be%20hospitalized .

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Salmonella Outbreak Linked to Onions. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 16, 2021. Accessed December 3, 2021.

Investigation Notice. September 24, 2021. Accessed September 28, 2021. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/Salmonella/oranienburg-09-21/details.html .

Minohara Y, Kato T, Chiba M. A rare case of Salmonella soft-tissue abscess. J Infect Chemother. 2002;8(2):185–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101560200033 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jiménez M, Martinez-Urtaza J, Rodriguez-Alvarez MX, Leon-Felix J, Chaidez C. Prevalence and genetic diversity of Salmonella spp. in a river in a tropical environment in Mexico. J Water Health. 2014;12(4):874–84.

Mendoza J, Botsford J, Hernandez J, et al. Microbial contamination and chemical toxicity of the Rio Grande. BMC Microbiol. 2004;4:17.

Teh J, Quinlan M, Bolton D. Salmonella Oranienburg hemorrhagic cystitis in an immunocompetent young male. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4(8)

Gremillion MDH, Geckler MR, Ellenbogen C. Salmonella abscess: a potential nosocomial hazard. Arch Surg. 1977;112(7):843–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1977.01370070057007 .

Lin C, Patel S. Salmonella prostatic abscess in an immunocompetent patient. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9122.

Poh CWM, Seah XFV, Chong CY, et al. Salmonella renal abscess in an immunocompetent child: case report and literature review. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333.

Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This study was conducted without funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of New Mexico, 2211 Lomas Blvd NE, Albuquerque, NM, 87106, USA

Brenda M. Castlemain

New Mexico Heart Institute, University of New Mexico, 2211 Lomas Blvd NE, Albuquerque, NM, 87106, USA

Brian D. Castlemain

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BMC wrote the introduction, discussion, conclusion. BDC wrote the case. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brenda M. Castlemain .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This case report is in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of New Mexico.

Consent for publication

Written consent for publication was obtained from the described patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Castlemain, B.M., Castlemain, B.D. Case report: post-salmonellosis abscess positive for Salmonella Oranienburg. BMC Infect Dis 22 , 337 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07217-5

Download citation

Received : 05 October 2021

Accepted : 25 February 2022

Published : 05 April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07217-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Salmonella Oranienburg

- Extraintestinal

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Salmonella enteritidis Phlegmon in an Elderly Female: A Case Report

Zurabi zaalishvili, tamar didbaridze, nino gogokhia, besik asanidze, lali akhmeteli, liana saginashvili, giorgi maziashvili.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Giorgi Maziashvili [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2022 Jul 31; Collection date 2022 Aug.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Salmonella enteritidis is an individual serotype of S. enterica which can cause gastroenteritis in humans. In the case of a mild primary infection, bacteremia and phlegmon, as well as other types of extraintestinal Salmonella infection, may go undiagnosed.

A 64-year-old female presents with a one-week history of fatigue, fever, and low back pain. She recently noticed a progressively growing mass in her lower back, along with swelling and redness of the surrounding skin. The patient is a nursing home resident who has been immobilized since a fall one month before the presentation. The bacterial culture of discharge from the infected area was found to be positive for S. enteritidis , and the diagnosis of the torso phlegmon was made. The patient underwent surgical removal of the phlegmon and clinically improved after post-operative treatment.

After evaluating geographic location, time of the year, and host factors such as relative immobility, extremes of age, and immunosuppressive conditions, S. enteritidis should be considered in a differential diagnosis of torso phlegmon.

Keywords: atypical infection, bacteremia, abscess, salmonella, phlegmon

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic rod. It spreads via the fecal-oral route and can be passed on through contaminated food and drink, direct animal contact, and, in rare cases, from person to person [ 1 ]. More than 2600 S. enterica serovars have been identified since the emergence of the disease in the 19th century, with many of these serovars capable of causing diseases in both humans and animals [ 2 ]. Enteric fever is caused by the human limited serovar Typhi and the closely related serovar Paratyphi-A, whereas non-typhoidal salmonellosis is caused by the generalist serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis [ 3 ]. Mousselli et al. described epidural phlegmon and iliopsoas abscess cases where S. enterica was identified as the causative organism [ 4 ]. However, there are no documented reports of S. enteritidis causing phlegmon. Here, we report a case of a 64-year-old female who developed S. enteritidis phlegmon on the torso.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old woman was hospitalized at the Tbilisi State Medical University (TSMU) The First University Clinic due to fatigue, fever, and low back pain on May 14, 2022. Her symptoms started one week ago. She noted a progressively increasing mass in her lower back with concomitant swelling and redness of the surrounding skin. She is a nursing home resident and has been bedbound since a fall one month before the presentation. Her past medical history is negative for recent gastrointestinal infections, diabetes, or immunocompromised states. However, it is significant for osteoarthritis treated with as-needed ibuprofen and hypertension diagnosed seven years ago and treated with captopril 25 mg since then.

On admission, her vital signs were significant for a temperature of 38.0 ℃ (100.4 ℉). The physical examination revealed a fluctuating mass (20 cm × 15 cm) with surrounding erythema and edema in the left lower back along the scapular line. A presumptive diagnosis of torso phlegmon was made and the following studies were ordered: complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), coagulation panel, C-reactive protein (CRP), chest X-ray (CXR), spinal MRI - T2 (FRFSE), T1 (FSE), STIR, viral hepatitis panel, HIV antibody test, VDRL, blood culture, and bacterial culture of pus from the mass.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of images or data included in this article.

Laboratory tests revealed abnormalities in the CBC and CRP, as shown in Table 1 . White blood cells (26.07 × 10 9 /L), neutrophils (86%), and CRP (159.6 mg/L) were all elevated. The hemoglobin level (10.3 g/dL), the percentage of lymphocytes (11.6%), and the hematocrit (32.5%) were all lower than normal.

Table 1. Abnormal laboratory values.

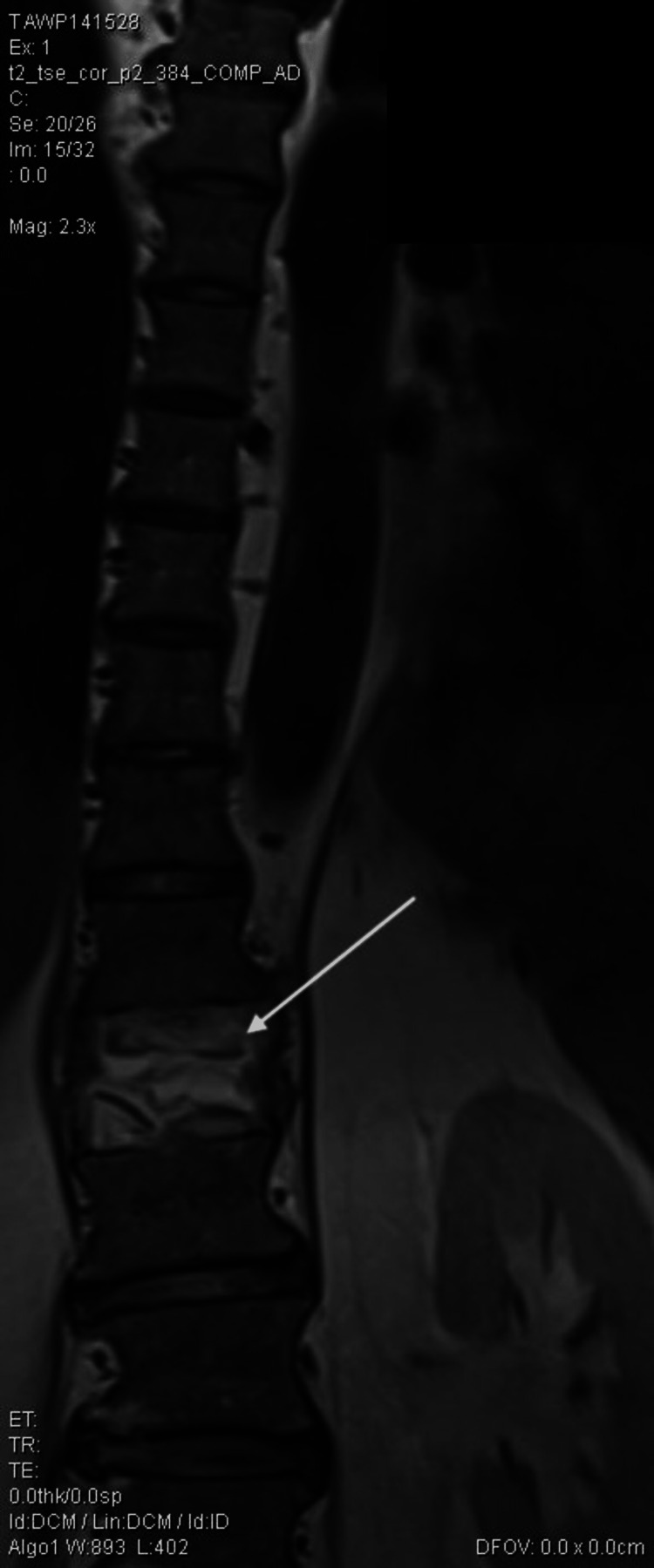

Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were nonspecific except for the previous T12 compression fracture, as seen in Figures 1 - 2 . The bacteriology laboratory of the clinic identified Salmonella spp. (10 8 CFU/ml) using the Analytical Profile Index (API) manual identification system (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France). Identification of the pathogen from the pus confirmed the diagnosis of torso phlegmon. The isolate was then sent to the reference laboratory for a serology study, which identified Salmonella enteritidis. The blood culture was negative. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) standard version 12 was used to assess antibiotic susceptibility against the following antibiotics: ceftriaxone, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, amikacin, imipenem, meropenem. As seen in Table 2 , the identified pathogen was sensitive to every tested antibiotic.

Table 2. Antibiotic susceptibility testing using the disc diffusion method (EUCAST Guidelines).

EUCAST: European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine in sagittal view. The white arrow indicates compression fracture.

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine in coronal view. The white arrow indicates compression fracture.

Other studies mentioned above did not reveal any significant findings. A general surgeon and a neurosurgeon were consulted. On May 15, 2022, the patient underwent surgical removal of phlegmon under general anesthesia. The procedure was performed without complications. The patient was transferred into the postoperative care unit with the following treatment regimen: ceftriaxone 1.0 × 2; metronidazole 500 mg/100 mL; enoxaparin 40 mg/0.4 mL; pantoprazole 40 mg × 1; diphenhydramine 10 mg/mL; captopril 25 mg; and metoclopramide 2 mL.

The patient improved significantly during the next five days in the hospital under the regular supervision of a general surgeon and an infectious disease specialist. The postoperative wound was cleaned daily with betadine solution. The patient was discharged on May 20, 2022, after proper counseling and education to prevent pressure ulcers and further torso infections.

Salmonellae belong to Gram-negative and facultatively anaerobic Enterobacteriaceae. The genus Salmonella is divided into two species: S. enterica and S. bongori [ 5 ]. S. enterica is further subdivided into six subspecies. Most clinically important salmonellae are formally classified into a single subspecies, S. enterica , subspecies enterica [ 5 ]. S. choleraesuis , S. typhi , S. typhimurium , and S. enteritidis are now identified as individual serotypes of this single subspecies [ 6 ].

Antimicrobial resistance patterns in nontyphoidal salmonellae vary significantly across the globe. Resistance to fluoroquinolones or third-generation cephalosporins is not widespread in the United States or Europe, but it warrants close monitoring. Salmonellae with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes are emerging in some areas [ 5 ].

Salmonellae can cause a variety of clinical infections, such as gastroenteritis, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, abscesses, and, rarely, phlegmon. Bacteremia and phlegmon, along with other types of extraintestinal Salmonella infection, may go unnoticed in the case of a mild primary infection [ 7 ]. Salmonella serotype, geographic location, time of year, and host factors such as relative immobility, extremes of age, and immunosuppressive conditions all influence the occurrence of bacteremia [ 7 , 8 ].

Our patient, who is a resident of a nursing home facility with poor sanitary conditions, developed S. enteritidis phlegmon on her lower back after being bedbound for one month. She had a stage 2 pressure ulcer on her back before the presentation, which could have been the source of infection. The abscess could be considered in a differential diagnosis; however, since the lesion was spreading along the tissue, this diagnosis has been ruled out. She reported no history of recent gastrointestinal infection, diabetes mellitus, or steroid administration. Although Salmonella phlegmon is relatively rare compared to other extraintestinal Salmonella infections, this case confirms how the patient’s comorbidities and poor sanitary conditions may predispose them to atypical infections. Additionally, physicians should keep a high index of suspicion for nontyphoidal Salmonella abscess/phlegmon when dealing with elderly immobile patients with infected subcutaneous masses.

Conclusions

S. enteritidis is most commonly associated with gastroenteritis. However, it is imperative to include this infection in the differential diagnosis for phlegmon in bedbound patients with a poor hygienic environment. Further spread of the infection can be effectively prevented with quick recognition, diagnosis, and treatment. We believe that educating the patients plays an equally crucial role in preventing such atypical infections in the future.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

- 1. Infection with Salmonella. [ Jul; 2022 ]; https://www.cdc.gov/training/SIC_CaseStudy/Infection_Salmonella_ptversion.pdf 2013

- 2. Isolation and molecular characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis from poultry house and clinical samples during 2010. Mezal EH, Sabol A, Khan MA, Ali N, Stefanova R, Khan AA. Food Microbiol. 2014;38:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.08.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Salmonella Typhi, Paratyphi A, Enteritidis and Typhimurium core proteomes reveal differentially expressed proteins linked to the cell surface and pathogenicity. Saleh S, Van Puyvelde S, Staes A, et al. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007416. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Epidural phlegmon and iliopsoas abscess caused by Salmonella enterica bacteremia: a case report. Mousselli M, Chiang E, Frousiakis P. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;96:107287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107287. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Hohmann EL. UpToDate. Waltham: UpToDate; [ Jul; 2022 ]. 2022. Nontyphoidal Salmonella: microbiology and epidemiology. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. MLST based serotype prediction for the accurate identification of non typhoidal Salmonella serovars. Jacob JJ, Rachel T, Shankar BA, Gunasekaran K, Iyadurai R, Anandan S, Veeraraghavan B. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:7797–7803. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05856-y. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Hohmann EL. UpToDate. Waltham: UpToDate; [ Jul; 2022 ]. 2020. Nontyphoidal Salmonella bacteremia. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (620.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Salmonella gastroenteritis is an infection that can result in serious and life-threatening complications in the pediatric population. Infants below the age of 12 months are especially at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Our case is a 4-month-old male who presents with gastroenteritis in the ED and evaluated for sepsis.

After completing this case study, the student should be able to: 1) describe the signs and symptoms, means of diagnosis, and control of salmonellosis 2) describe how Salmonella serotyping can be used in public health practice 3) given a disease, describe the desired characteristics of a surveillance system for that disease

Here we describe a Salmonella infected sternocostal joint abscess that began development 2–3 months after Salmonella gastroenteritis treated successfully with intravenous antibiotics in an otherwise healthy patient.

PDF | This case study is centered on the events of Salmonellosis outbreak in the Caribbean between the mid 1980s and late 2000s. This outbreak was... | Find, read and cite all the research...

Globally, invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS) infection is increasing and has emerged as one of the leading causes of morbidity and deaths in sub-Saharan Africa. 1 We describe a case of iNTS infection with multi-organ involvement, which is extremely rare in the developed world.

After completing this case study, the student should be able to: 1) describe the signs and symptoms, means of diagnosis, and control of salmonellosis 2) describe how Salmonella serotyping can be used in public health practice 3) given a disease, describe the desired characteristics of a surveillance system for that disease

A new computer-based case study, "Salmonella in the Caribbean," is now available from CDC. This self-instructional, interactive exercise is based on an outbreak investigation conducted in Trinidad and Tobago.

Salmonella is a causative agent of bacterial gastroenteritis. Some symptoms are fever and diarrhea, Intravenous rehydration is the primary treatment and antibiotics are only given in high risk groups.

Here we describe a Salmonella infected sternocostal joint abscess that began development 2–3 months after Salmonella gastroenteritis treated successfully with intravenous antibiotics in an otherwise healthy patient.

Salmonella enteritidis is an individual serotype of S. enterica which can cause gastroenteritis in humans. In the case of a mild primary infection, bacteremia and phlegmon, as well as other types of extraintestinal Salmonella infection, may go undiagnosed.