- Cord presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created Yuranga Weerakkody had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Joshua Yap had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Funic presentation

- Cord (funic) presentation

A cord presentation (also known as a funic presentation or obligate cord presentation ) is a variation in the fetal presentation where the umbilical cord points towards the internal cervical os or lower uterine segment.

It may be a transient phenomenon and is usually considered insignificant until ~32 weeks. It is concerning if it persists past that date, after which it is recommended that an underlying cause be sought and precautionary management implemented.

On this page:

Epidemiology, radiographic features, treatment and prognosis, differential diagnosis.

- Cases and figures

The estimated incidence is at ~4% of pregnancies.

Associations

Recognized associations include:

marginal cord insertion from the caudal end of a low-lying placenta

uterine fibroids

uterine adhesions

congenital uterine anomalies that may prevent the fetus from engaging well into the lower uterine segment

cephalopelvic disproportion

polyhydramnios

multifetal pregnancy

long umbilical cord

Color Doppler interrogation is extremely useful and shows cord between the fetal presenting part and the internal cervical os. However, unlike a vasa previa , the placental insertion is usually normal.

As the complicating umbilical cord prolapse can lead to catastrophic consequences, most advocate an elective cesarean section delivery for persistent cord presentation in the third trimester 3 .

Complications

It can result in a higher rate of umbilical cord prolapse .

For the presence of umbilical cord vessels between the fetal presenting part and the internal cervical os on ultrasound consider:

vasa previa

- 1. Ezra Y, Strasberg SR, Farine D. Does cord presentation on ultrasound predict cord prolapse? Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2003;56 (1): 6-9. doi:10.1159/000072323 - Pubmed citation

- 2. Kinugasa M, Sato T, Tamura M et-al. Antepartum detection of cord presentation by transvaginal ultrasonography for term breech presentation: potential prediction and prevention of cord prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2007;33 (5): 612-8. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00620.x - Pubmed citation

- 3. Raga F, Osborne N, Ballester MJ et-al. Color flow Doppler: a useful instrument in the diagnosis of funic presentation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88 (2): 94-6. - Free text at pubmed - Pubmed citation

- 4. Bluth EI. Ultrasound, a practical approach to clinical problems. Thieme Publishing Group. (2008) ISBN:3131168323. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Variation in fetal presentation

- Vasa praevia

- Umbilical cord prolapse

- Vasa previa

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Editorial Board

TheFetus.net

Umbilical cord prolapse.

Address correspondence to Val Catanzarite, MD, PhD, Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Mary Birch Hospital for Women at Sharp Memorial Hospital, 8010 Frost Street, Suite M, San Diego, CA 92123-2788 Ph: 619-541-6880; Fax: 619-541-6899

Synonyms: Funic presentation, cord presentation.

Definitions: Cord or funic presentation denotes the finding by sonography or clinical examination of the umbilical cord interposed between the leading part of the fetus and the internal cervical os. Umbilical cord prolapse can be used synonymously, but usually denotes egress of the cord beyond the cervix, in advance of the leading part of the fetus, usually in the presence of ruptured membranes.

Prevalence: 12-25:10,000 pregnancies 1,2 .

Etiology: Variable; see text.

Associated (and consequential) abnormalities: Funic presentation and umbilical cord prolapse are increased in frequency with malpresentation (breech and transverse), polyhydramnios, maternal pelvic deformities, uterine abnormalities such as myomata, multiple gestation, and low-lying placenta or marginal placenta previa 3 .

Differential diagnosis: Vasa previa.

Prognosis: Depends upon fetal condition at the time of diagnosis, status of the cervix, and appropriate intervention.

Recurrence risk: Low, unless there is a persistent causative factor, e.g.: maternal pelvic deformity or uterine myomata.

Management: Controversial for funic presentation with a closed cervix. Delivery, usually by cesarean section, is indicated for funic presentation diagnosed during labor or umbilical cord prolapse 4,5,6 .

MESH Umbilical Cord ICD9 7624 CDC 7624.1

Introduction

Funic presentation is a condition in which the umbilical cord is interposed between the leading part of the fetus and the internal os of the uterine cervix. Funic presentation, even during early labor, is often not clinically suspected. When the cervix is minimally dilated, the cord may not be palpable on examination, and the fetal heart rate tracing is often normal or shows mild or moderate variable decelerations, a common and usually innocuous pattern. As labor progresses, umbilical cord compression associated with contractions causes increasingly severe variable decelerations. When membranes rupture, if the cord prolapses through the cervix, it is compressed with every contraction; severe variable decelerations and/or profound fetal bradycardia may occur. Umbilical cord prolapse constitutes an obstetric emergency with potential for fetal death 4,6 .

Much more is known about umbilical cord prolapse than about funic presentation, since the former is a dramatically apparent clinical diagnosis and the latter is usually diagnosed by sonography in the asymptomatic patient. The rate of umbilical cord prolapse is much lower in the vertex presenting fetus than in the fetus with breech presentation or transverse lie; the overall risk in vertex presentation is quoted at 0.2 to 0.4%, in all breech presentations 3.5%, and in transverse lie or footling breech presentation, approximately 10%. The relative risk notwithstanding, because the fetal presentation during labor is vertex in 96-98% of patients, the total number of cases of umbilical cord prolapse is greater for vertex than non-vertex presentation 3 .

Here, we describe the sonographic diagnosis of incipient umbilical cord prolapse in a patient with vertex presentation in preterm labor.

Case report

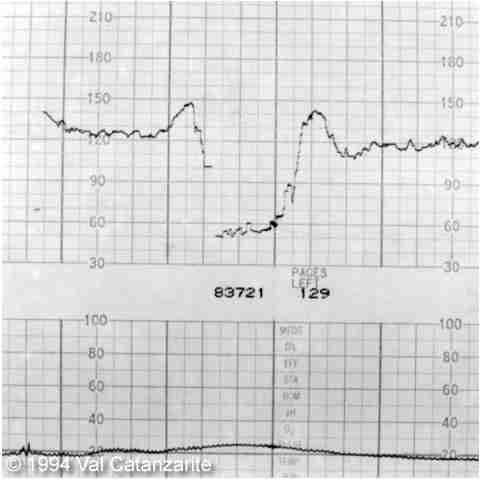

The patient is a G 2 , now P1-1-0-2 admitted at 35 weeks" gestation with idiopathic preterm labor. At the time of admission, the cervix was 2 cm dilated and 80% effaced with a ballottable vertex presenting. The fetal heart rate tracing was reactive, and no decelerations were seen. The patient was having regular, painful contractions. Tocolytic therapy with terbutaline and then intravenous magnesium sulfate was instituted. The next morning, contractions recurred, and the cervix dilated to 3 cm at 80% effacement, with a bulging bag of waters and ballottable vertex presentation. There was no suspicion of funic presentation on exam, but the fetal heart rate tracing showed several moderate variable decelerations and a severe variable deceleration (fig. 1). Sonographic evaluation was requested.

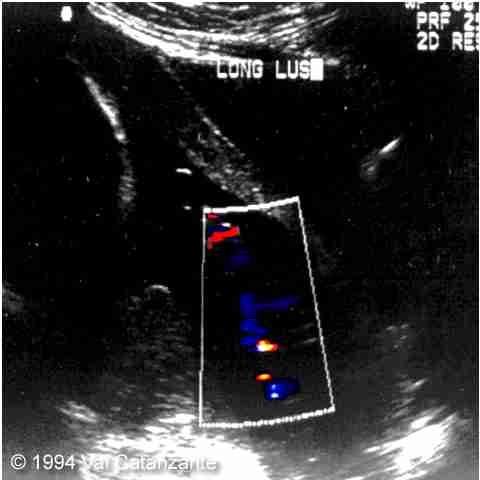

A longitudinal view of the lower uterine segment is presented as figure 2. The ultrasound scan showed loops of umbilical cord between the vertex and the dilated internal cervical os, both on real-time and color-flow studies. Careful examination of the lower uterine segment and lower placental edge with real-time and color-flow techniques showed no evidence of vasa previa. The patient was given adjunctive terbutaline subcutaneously to maintain tocolysis while preparations were made for expeditious cesarean section. This was performed under spinal anesthesia without incident. The infant was a 2885g, Apgar 4/8 female. She had mild transient tachypnea but was off of oxygen within 48 hours and home within four days.

The first reported case of prenatal diagnosis of funic presentation or occult cord prolapse was in 1979, when Christopher, Spinelli, and Collins diagnosed funic presentation in two patients in the late mid- trimester with hourglass membranes and malpresentation of the fetus7. Subsequent reports have described diagnoses of funic presentation by means of transabdominal and transperineal sonography and, more recently, with the use of Doppler studies 8-12 . Only one previously diagnosed case not associated with malpresentation has been documented. The patient reported by Hales and Weatney8 was seen at 37 weeks" gestation for abdominal pain and was found to have a fetus in vertex orientation with funic presentation. The fetal monitor tracing was not described; the patient was not in labor but was delivered by cesarean section due to concerns regarding cord prolapse.

Differential diagnosis

It is of paramount importance to differentiate funic presentation from vasa previa, and the sonographic differentiation may be quite difficult. If the umbilical cord insertion into the placenta is clearly demonstrable, and the placenta does not have a succenturiate lobe, then vasa previa is not possible. However, we have diagnosed cases of vasa previa by ultrasound in which the umbilical cord inserted into one lobe of the placenta, and large vessels connecting the larger placental mass to a smaller succenturiate lobe coursed directly over the internal cervical os WE have also seen a case in which an anterior low-lying placenta had a velamentous cord insertion into its lower margin, from which vessels crossed over the cervix, exited the membranes on the posterior wall of the uterus, and gave a sonographic appearance of multiple loops of umbilical cord filling the lower uterine segment simulating funic presentation.

The differentiation between funic presentation and vasa previa may be possible by means of filling the patient"s bladder and tilting her into Trendelenburg position; cord loops from funic presentation may move away from the cervix, whereas the vessels in vasa previa (since they run within the membranes) remain unchanged in this position. Transvaginal sonography may also be helpful in the differential diagnosis. Vasa previa is a dangerous condition, with a high likelihood of fetal death from exsanguination when the membranes rupture, and management must be carefully individualized.

Antepartum diagnosis

Pelosi 12 and Lange et al 9 have advocated screening for funic presentation as a part of antenatal testing late in pregnancy. For example, Lange et al reported that 9 of 1,471 patients at or beyond 37 weeks" gestation had funic presentation. It resolved in one case, cord prolapse and fetal death occurred in one case and the remaining patients were delivered by cesarean section for malpresentation. All were confirmed to have funic presentation at the time of delivery. However, in their series, there was no mention of whether or not the cervix was dilated at the time of evaluation. Additionally, the fetus was in a non-vertex presentation in all of their cases. The authors favored intervention (delivery) in cases of persistent cord presentation, but this is controversial; it could be argued that careful external version could correct both the cord position and fetal malpresentation, and allow vaginal delivery.

Intrapartum diagnosis

The sonographic diagnosis of funic presentation during labor when the cervix is dilated is a different matter entirely. Funic presentation per se is seldom a true emergency while the membranes are intact. However, upon rupture of the membranes, umbilical cord compression and fetal distress are the rule. Few situations will strike fear into the heart of the obstetrician/gynecologist or radiologist in the same way as diagnosis of funic presentation with cervical dilatation in an office outside the hospital setting !

In principle, it should be straightforward to diagnose funic presentation during labor, if the presenting part is high and the condition is searched for by ultra¬sound. In the patient at or near term, with non-vertex presentation, in labor, the usual plan of management is cesarean section, so that the diagnosis would not impact treatment. Given the frequency of cord prolapse, it is surprising that funic presentation or occult cord prolapse is not diagnosed more often during labor. We have made the diagnosis by ultrasound in three other cases over the past five years; two of these cases were associated with malpresentation and one with twins.

As discussed above, the management of funic presentation when the cervix is closed, prior to the onset of labor, is problematic. Hospitalization or delivery is the management plan advocated by Lange et al9. Fetal monitoring during fundal pressure to assess for cord compromise is espoused by Pelosi12, with consideration of delivery if fetal monitoring suggests umbilical cord compression. I would argue instead for consideration of external cephalic version in the non-vertex fetus with funic presentation in late pregnancy, followed by induction of labor. The cord position usually changes during version, and vaginal delivery without complications may be possible.

When funic presentation is diagnosed during labor in a nonvertex presentation, cesarean section is indicated. For patients diagnosed with a vertex fetus and funic presentation, two management options could, in theory, be considered. Barrett5 recently reported a series of patients with cord prolapse in whom funic replacement was attempted; the majority delivered vaginally. However, these patients were in advanced labor when prolapse occurred. For the patient with cervical dilatation of 80mm, or funic presentation with a second twin, it may be reasonable to try vaginal delivery in the operating room, and with a full team ready for cesarean section. Earlier in labor, the diagnosis of funic presentation affords the opportunity to perform a cesarean section under controlled conditions and avert the potentially disastrous situation of cord prolapse.

1. Barclay ML. Umbilical cord prolapse and other cord accidents, In: Sciarra JJ, ed. Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol 2. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott; chap 78 pp 1-7, 1989.

2. Moir JC. Monro Kerr"s Operative obstetrics. London: Baili/Àre, Tindall and Cox p259, 1964.

3.Dildy GA, Clark SL. Umbilical cord prolapse. Contemp Obstet Gynecol 38:23-32, 1993.

4. Koonings PP, Paul RH, Campbell K. Umbilical cord prolapse: A contemporary look. J Reprod Med 35:690, 1990.

5. Barrett JM. Funic reduction for the management of umbilical cord prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 165:654, 1991.

6. Katz Z, Shoham (Schwartz) Z, Lancet M et al,: Management of labor with umbilical cord prolapse: A 5-year study. Obstet Gynecol 72:278, 1988.

7. Christopher CR, Spinelli A, Collins ML. Ultrasonic detection of hourglass membranes with funic presentation. Obstet Gynecol 54:130, 1979.

8. Hales ED, Weatney LS. Sonography of occult cord prolapse. JCU 12:283-285, 1984.

9. Lange IR, Manning FA, Morrison I, et al,: Cord prolapse: is antenatal diagnosis possible? Am J Obstet Gynecol 151:1083-5, 1985.

10. Johnson RL, Anderson JC, Irsik RD, et al.: Duplex ultrasound diagnosis of umbilical cord prolapse. JCU 15:282-284, 1987.

11. Sakamoto H, Takagi K, Masaoka N, et al. Clinical application of the perineal scan: prepartum screening for cord presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 155:1041-3, 1986.

12. Pelosi M. Antepartum ultrasonic diagnosis of cord presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 162:599-601, 1990.

Discussion Board

- Discussions

- Create an Account

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 5

- Cord presentation in labour: imminent risk of cord prolapse

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Tiago Aguiar 1 , 2 ,

- João Cavaco Gomes 1 and

- Teresa Rodrigues 2

- 1 Gynaecology Department , Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João , Porto , Portugal

- 2 Obstetrics Department , Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João , Porto , Portugal

- Correspondence to Dr Tiago Aguiar; tiagomdiasaguiar{at}gmail.com

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-243320

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- obstetrics and gynaecology

- reproductive medicine

Description

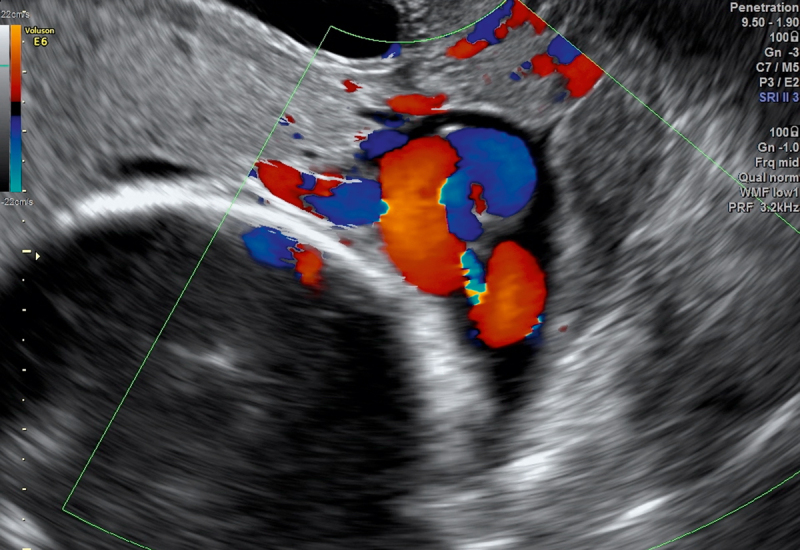

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 39 weeks of gestation, gravida 3, para 2, with a history of uncomplicated spontaneous vaginal deliveries at term, presented to the emergency department with lower abdominal cramps and watery vaginal discharge that started 2 hours before. Vaginal examination confirmed ruptured membranes, 3 cm cervical dilation, 30% effacement, and a mass of umbilical cord loops was presenting. Transvaginal ultrasound demonstrated an agglomerate of umbilical cord loops lying between the internal os and the fetal head ( figures 1 and 2 ). Due to the imminent possibility of overt cord prolapse, an emergent caesarean section was performed, with the delivery of a newborn weighing 3640 g, Apgar score 9 at 1 min and 10 at 5 min.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Transvaginal ultrasound showing the umbilical cord between the fetal head and the cervix.

Transvaginal ultrasound showing loops of cord presenting above the internal cervical os. Flow confirmed with colour Doppler.

Suspicion may arise during vaginal examination but the diagnosis may not clear. Ultrasound can confirm the diagnosis by showing the presence of umbilical cord between the fetal presenting part and the cervix.

Spontaneous resolution by time of delivery can occur when the diagnosis is established during third trimester scan. However, the combination of ruptured membranes and cord presentation during labour precedes an inevitable cord prolapse, as cervical dilation progress. Therefore, we agree with the majority of authors recommending caesarean section when funic presentation is found during labour. 4

Learning points

Cord presentation is a rare condition during labour, associated with imminent risk of cord prolapse.

Diagnosis may be suspected during vaginal examination and is confirmed by ultrasound.

Caesarean section is recommended when diagnosis is established during labour.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

- Strasberg SR ,

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)

- Matsuzaki S , et al

- Grenier S ,

Contributors All authors were responsible for the diagnosis and management of the case reported. Dr TA was responsible for writing of the report. Dr JCG and Professor TR were responsible for the corrections before submission of the document.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Persistent Funic Presentation And Sonographic Assesment Of The Risk For Umbilical Cord Prolapse

Ioakeim sapantzoglou, alexandros psarris, panagiota diamantopoulou, antonis koutras, thomas ntounis, savia pittokopitou, ioannis prokopakis, panagiotis antsaklis, marianna theodora, michail sindos, ekaterini domali, alexandros rodolakis, georgios daskalakis.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence Dr. Alexandros Psarris National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, First Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, V. Sofias 80 and Lourou Street, 11528 Athens, Greece, Phone: 6979232977, Email: [email protected]

Collection date 2023 Jan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License, which permits unrestricted reproduction and distribution, for non-commercial purposes only; and use and reproduction, but not distribution, of adapted material for non-commercial purposes only, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Funic presentation (also known as cord presentation) is a rare entity with an incidence that ranges from 0.006% to 0.16% in the third trimester scans (Ezra et al., Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003; 56 : 6–9. 2003) and is defined as the presence of the cord between the presenting part of the fetus and the internal cervical os, with or without intact membranes (“Umbilical Cord Prolapse (Green-top Guideline No. 50) | RCOG,” n.d.). It may be a transient phenomenon and is usually considered insignificant until ~32 weeks. However, its persistence beyond that gestational age raises the concern of cord prolapse during labor as cervical dilation progresses. Consequently, current bibliography recommends Caesarean delivery when funic presentation is detected during labor making antenatal ultrasound detection a valuable asset in the effort to prevent the complications that cord prolapse has been associated with (Jones et al., BJOG 2000; 107 : 1055–7 ). Cord prolapse is the most significant complication of funic presentation and as such, the antenatal detection of cord presentation cases and the determination of patients that carry an increased risk for UCP are of paramount importance.

It is a mostly unpredictable obstetric emergency, in which the umbilical cord comes through the cervical os in advance of ( overt prolapse – usually palpable or even visible within the vagina) or alongside ( occult prolapse) the fetal presenting part in the presence of ruptured membranes. The reported incidence of umbilical cord prolapse ranges from 1 to 6 per 1000 pregnancies (Faiz et al., Saudi Med J 2003; 24: 754–7).Though rare, it is associated with high perinatal mortality and morbidity as cord compression and umbilical artery vasospasm may occur preventing blood flow to and from the fetus leading to fetal asphyxia (Critchlow et al., Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 170: 613–8).

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old pregnant woman at 32+2 weeks of gestation, gravida 5, para 4, presented to the outpatient clinic of our institution during the third trimester of her pregnancy, due to painless vaginal bleeding. The antenatal course had been otherwise uncomplicated. The woman’s past medical history was uneventful.

During her pregnancy, she underwent no prenatal testing except for a first trimester scan at 9 weeks of gestation where the exact gestational age was determined.

She had previously had four uncomplicated pregnancies, having delivered vaginally the first two, while the third and the fourth pregnancies were delivered via caesarean section – the first one because of a footling breech presentation and the other one because of the previous caesarean section. The woman was hemodynamically stable, and the biophysical profile was normal.

The sonographic examination revealed a singleton pregnancy with positive cardiac function and an anterior low-lying placenta with its lower edge 24.8 mm from the internal os ( Fig. 1 ). The cord insertion was noted to be marginal towards the lower placental edge ( Fig. 1 ). Furthermore, multiple free loops of the umbilical cord were noted to be running over the internal cervical os ( Fig. 2 ). The cervix measured 24 mm in length with funneling at the time.

Transvaginal ultrasound revealed a marginal cord insertion in the placenta close to the lower placental edge.

Umbilical cord free loops were detected overlying the cervical internal os.

All fetal growth parameters, the amniotic fluid index and the Doppler assessment were within normal range for the gestational age (EFW: 2342gr (89th percentile)).

A single course of antenatal corticosteroids was given at 32+2 and 32+3 weeks of gestation, due to the fear of an impending umbilical cord prolapse.

The pregnancy was followed up with weekly ultrasound scans. The free loops remained in close proximity to the internal os, lying between the presenting part and the cervix. The pregnancy was monitored until 36+0 weeks of gestation, when the patient began complaining of regular contractions, a fact that was confirmed with the use of cardiotocography. A new ultrasound examination was performed with the umbilical cord loops still present between the fetal head and the cervix and an emergency caesarean section was performed.

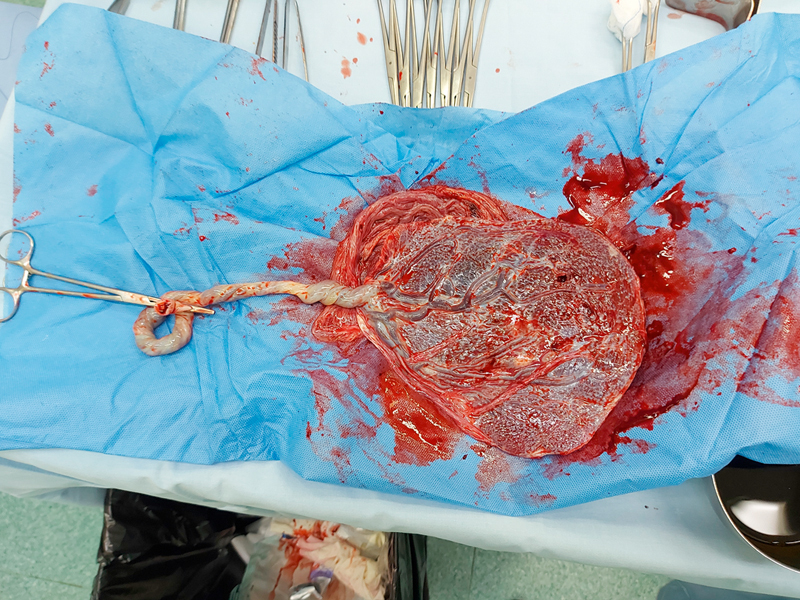

A live, female newborn was delivered, weighing 3040 g with Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The gross examination of the placenta confirmed the marginal cord insertion of the umbilical cord ( Fig. 3 ).

Τhe examination of the placenta postpartum confirmed the marginal cord insertion.

Identification and antenatal detection of umbilical cord presentation cases are of utmost importance due to their association with umbilical cord prolapse, which is linked to significant perinatal mortality and morbidity. The current paper presents a case of funic presentation at our department and the management that was carried out and also provides a summary of all of the available published evidence on the association between funic (cord) presentation and cord prolapse. The studies by Vintzileos et al.( J Clin Ultrasound. 1983 Nov-Dec; 11(9): 510–1) and Raga et al. (J Natl Med Assoc. 1996; 88(2): 94–6) describe cord presentation as the precursor to impending cord prolapse, thus highlighting the need for focused ultrasound imaging to diagnose and manage these pregnancies and then to plan the delivery of these fetuses by cesarean section.

In contrast, (Ezra et al., Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003; 56 : 6–9) demonstrated that cord prolapse was preceded by the identification of cord presentation via routine ultrasound in just 12.5% of cases. In addition, a considerable proportion of funic presentation cases diagnosed antenatally resolved spontaneously without resulting in cord prolapse (4 out of 7 turned to vertex presentation), underlining that the two conditions are not synonymous. The authors, however, stated that the sonographic finding of cord presentation carries a significant risk of cord prolapse given the fact that, in their dataset, 1 out of 13 women with cord presentation had a clinical prolapse. Contradictory to the above results, there is some case report evidence underlining the necessity of the assessment of the position of the placental cord insertion in funic presentations since it is the author’s belief that the anatomic relationship between the internal os and the marginal or velamentous cord insertions would preclude the possibility of such a resolution (Oyelese et al., Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 24(6): 692–3).

In terms of following up the pregnancies with cord presentation, there is only one cohort study with historical controls that assessed the efficacy of weekly internal ultrasound examinations in women with breech fetuses after 36 weeks of gestation (Kinugasa et al., J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007; 33(5): 612–8). There were no cases of cord prolapse when such a screening method was adopted, in a 10-year period (1995–2005), while in the historic control group there were 10 cases of cord prolapse noted along with one perinatal death in an 11-year period (1983–1994). The authors agreed with Ezra et al. that the two conditions are not synonymous and underlined the importance of serial transvaginal ultrasound assessments given the fact that there were cases in which there were no funic presentations initially, but they developed eventually.

It is well established that transvaginal ultrasound is the best available modality to diagnose a funic presentation and it is a great tool to differentiate it from vasa previa, a condition in which the fetal vessels traverse the membranes near the internal os in advance of the fetal presenting part. In funic presentation cases, the umbilical cord moves away from the cervix during ultrasound examination whereas in vasa previa the cord remains fixed in place. However, there is currently no definitive consensus regarding the optimal timing of delivery in cases of funic presentation. Some researchers advocate close monitoring in an effort to achieve vaginal delivery, while others recommend scheduled cesarean delivery prior to the onset of labor (Jones et al., BJOG 2000; 107 : 1055–7). Current evidence, based on the data provided by Ezra et al., is inclined towards a more personalized approach to the condition given the fact that funic presentation will not inevitably lead to prolapse (Jones et al., BJOG 2000; 107 : 1055–7). However, several cases of cord prolapse did not appear to have detectable cord presentations prenatally. Weekly ultrasound examination could be performed, and vaginal delivery could be considered in cases of resolution of the funic presentation.

The presence of funic presentation has been established as a documented risk factor for cord prolapse and its detection prenatally raises the risk of such an adverse event during labor. Ultrasound assessment is a well-established tool for the prenatal detection of cord presentation but the evidence regarding the proper management and the timing and mode of delivery is quite limited as it is the result of case reports and retrospective cohorts. The need for randomized controlled studies or case-control studies with a larger sample size should be emphasized in an effort to ameliorate the situation and optimize the management of the care of these pregnant women.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (420.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES