May 9, 2019

In Fraud We Trust: Top 5 Cases of Misconduct in University Research

There’s a thin line between madness and immorality. This idea of the “mad scientist” has taken on a charming, even glorified perception in popular culture. From the campy portrayal of Nikola Tesla in the first issue of Superman, to Dr. Frankenstein, to Dr. Emmet Brown of Back to the Future, there’s no question Hollywood has softened the idea of the mad scientist. So, I will not paint the scientists involved in these five cases of research fraud as such. The immoral actions of these researchers didn’t just affect their own lives, but also the lives and careers of innocent students, patients, and colleagues. Academic fraud is not only a crime, it is a threat to the intellectual integrity upon which the evolution of knowledge rests. It also compromises the integrity of the institution, as any institution will take a blow to their reputation for allowing academic misconduct to go unnoticed under its watch. Here, you will find the top five most notorious cases of fraud in university research in only the last few years

Fraud in Psychology Research

In 2011, a Dutch psychologist named Diederik Stapel committed academic fraud in a number of publications over the course of ten years, spanning three different universities: the University of Groningen, the University of Amsterdam, and Tilburg University.

Among the dozens of studies in question, most notably, he falsified data on a study which analyzed racial stereotyping and the effects of advertisements on personal identity. The journal Science published the study, which claimed that one particular race stereotyped and discriminated against another particular race in a chaotic, messy environment, versus an organized, structured one. Stapel produced another study which claimed that the average person determined employment applicants to be more competent if they had a male voice. As a result, both studies were found to be contaminated with false, manipulated data.

Psychologists discovered Stapel’s falsified work and reported that his work did not stand up to scrutiny. Moreover, they concluded that Stapel took advantage of a loose system, under which researchers were able to work in almost total secrecy and very lightly maneuver data to reach their conclusions with little fear of being contested. A host of newspapers published Stapel’s research all over the world. He even oversaw and administered over a dozen doctoral theses; all of which have been rendered invalid, thereby compromising the integrity of former students’ degrees.

“I have failed as a scientist and a researcher. I feel ashamed for it and have great regret,” lamented Stapel to the New York Times. You can read the particulars of this fraud case here .

Duke University Cancer Research Fraud

In 2010, Dr. Anil Potti left Duke University after allegations of research fraud surfaced. The fraud came in waves. First, Dr. Potti flagrantly lied about being a Rhodes Scholar to attain hundreds of thousands of dollars in grant money from the American Cancer Society. Then, Dr. Potti was caught outright falsifying data in his research, after he discovered one of his theories for personalized cancer treatment was disproven. This theory was intended to justify clinical trials for over a hundred patients. Because it was disproven, the trials could no longer take place. Dr. Potti falsified data in order to continue with these trials and attain further funding.

Over a dozen papers that he published were retracted from various medical journals, including the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Potti had been working on personalized cancer treatment he hailed as “the holy grail of cancer.” There are a lot of people whose bodies fail to respond to more traditional cancer treatments. Personalized treatments, however, offer hope because patients are exposed to treatments that are tailored to their own unique body constitution, and the type of tumors they have. Because of this, patients flocked to Duke to register for trials for these drugs. They were even told there was an 80% chance that they would find the right drug for them. The patients who partook in these trials filed a lawsuit against Duke, alleging that the institution performed ill-performed chemotherapy on participants. Patients were so excited that there was renewed hope for their cancer treatment, that they trusted Dr. Potti’s trials and drugs. Sadly, many of these cancer patients suffered from unusual side effects like blood clots and damaged joints.

Duke settled these lawsuits with the families of the patients. You can read details of the case here .

Plagiarism in Kansas

Mahesh Visvanathan and Gerald Lushington, two computer scientists from the University of Kansas, confessed to accusations of plagiarism. They copied large chunks of their research from the works of other scientists in their field. The plagiarism was so ubiquitous that even the summary statement of their presentation was lifted from another scientist’s article in a renowned journal.

Visvanathan and Lushington oversaw a program at the University of Kansas in which researchers reviewed and processed large amounts of data for DNA analysis. In this case, Visvanathan committed the plagiarism and Lushington knowingly refrained from reporting it to the university. Learn more about this case here .

Columbia University Research Misconduct

The year was 2010. Bengü Sezen was finally caught falsifying data after ten years of continuously committing fraud. Her fraudulent activity was so blatant that she even made up fake people and organizations in an effort to support her research results. Sezen was found guilty of committing over 20 acts of research misconduct, with about ten research papers recalled for redaction due to plagiarism and outright fabrication.

Sezen’s doctoral thesis was fabricated entirely in order to produce her desired results. Additionally, her misconduct greatly affected the careers of other young scientists who worked with her. These scientists dedicated a large portion of their graduate careers trying to reproduce Sezen’s desired results.

Columbia University moved to retract her Ph.D in chemistry. Sezen fled the country during her investigation. Read further details about this case here .

Penn State Fraud

In 2012, Craig Grimes ripped off the U.S. government to the tune of $3 million. He pleaded guilty to wire fraud, money laundering, and engaging in fraudulent statements to attain grant money.

Grimes bamboozled the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) into granting him $1.2 million for research on gases in blood, which helps detect disorders in infants. Sadly, it was revealed by the Attorney’s Office that Grimes never carried out this research, and instead used the majority of his granted funds for personal expenditures. In addition to that $1.2 million, Grimes also falsified information that helped him attain $1.9 million in grant money via the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Consequently, a federal judge ruled that Grimes spend 41 months in prison and pay back over $660,000 to Penn State, the NIH, and the NSF.

Check out the details about this case here .

Share this:

Latest articles, how to keep your orcid profile current .

Cory Thaxton

Toxic Labs and Research Misconduct

Digital persistent identifiers and you, featured articles.

August 15, 2024

November 21, 2023

November 16, 2023

Annual Review of Ethics Case Studies

What are research ethics cases.

For additional information, please visit Resources for Research Ethics Education

Research Ethics Cases are a tool for discussing scientific integrity. Cases are designed to confront the readers with a specific problem that does not lend itself to easy answers. By providing a focus for discussion, cases help staff involved in research to define or refine their own standards, to appreciate alternative approaches to identifying and resolving ethical problems, and to develop skills for dealing with hard problems on their own.

Research Ethics Cases for Use by the NIH Community

- Theme 24 – Using AI in Research and Ethical Conduct of Clinical Trials (2024)

- Theme 23 – Authorship, Collaborations, and Mentoring (2023)

- Theme 22 – Use of Human Biospecimens and Informed Consent (2022)

- Theme 21 – Science Under Pressure (2021)

- Theme 20 – Data, Project and Lab Management, and Communication (2020)

- Theme 19 – Civility, Harassment and Inappropriate Conduct (2019)

- Theme 18 – Implicit and Explicit Biases in the Research Setting (2018)

- Theme 17 – Socially Responsible Science (2017)

- Theme 16 – Research Reproducibility (2016)

- Theme 15 – Authorship and Collaborative Science (2015)

- Theme 14 – Differentiating Between Honest Discourse and Research Misconduct and Introduction to Enhancing Reproducibility (2014)

- Theme 13 – Data Management, Whistleblowers, and Nepotism (2013)

- Theme 12 – Mentoring (2012)

- Theme 11 – Authorship (2011)

- Theme 10 – Science and Social Responsibility, continued (2010)

- Theme 9 – Science and Social Responsibility - Dual Use Research (2009)

- Theme 8 – Borrowing - Is It Plagiarism? (2008)

- Theme 7 – Data Management and Scientific Misconduct (2007)

- Theme 6 – Ethical Ambiguities (2006)

- Theme 5 – Data Management (2005)

- Theme 4 – Collaborative Science (2004)

- Theme 3 – Mentoring (2003)

- Theme 2 – Authorship (2002)

- Theme 1 – Scientific Misconduct (2001)

For Facilitators Leading Case Discussion

For the sake of time and clarity of purpose, it is essential that one individual have responsibility for leading the group discussion. As a minimum, this responsibility should include:

- Reading the case aloud.

- Defining, and re-defining as needed, the questions to be answered.

- Encouraging discussion that is “on topic”.

- Discouraging discussion that is “off topic”.

- Keeping the pace of discussion appropriate to the time available.

- Eliciting contributions from all members of the discussion group.

- Summarizing both majority and minority opinions at the end of the discussion.

How Should Cases be Analyzed?

Many of the skills necessary to analyze case studies can become tools for responding to real world problems. Cases, like the real world, contain uncertainties and ambiguities. Readers are encouraged to identify key issues, make assumptions as needed, and articulate options for resolution. In addition to the specific questions accompanying each case, readers should consider the following questions:

- Who are the affected parties (individuals, institutions, a field, society) in this situation?

- What interest(s) (material, financial, ethical, other) does each party have in the situation? Which interests are in conflict?

- Were the actions taken by each of the affected parties acceptable (ethical, legal, moral, or common sense)? If not, are there circumstances under which those actions would have been acceptable? Who should impose what sanction(s)?

- What other courses of action are open to each of the affected parties? What is the likely outcome of each course of action?

- For each party involved, what course of action would you take, and why?

- What actions could have been taken to avoid the conflict?

Is There a Right Answer?

Acceptable solutions.

Most problems will have several acceptable solutions or answers, but it will not always be the case that a perfect solution can be found. At times, even the best solution will still have some unsatisfactory consequences.

Unacceptable Solutions

While more than one acceptable solution may be possible, not all solutions are acceptable. For example, obvious violations of specific rules and regulations or of generally accepted standards of conduct would typically be unacceptable. However, it is also plausible that blind adherence to accepted rules or standards would sometimes be an unacceptable course of action.

Ethical Decision-Making

It should be noted that ethical decision-making is a process rather than a specific correct answer. In this sense, unethical behavior is defined by a failure to engage in the process of ethical decision-making. It is always unacceptable to have made no reasonable attempt to define a consistent and defensible basis for conduct.

This page was last updated on Friday, July 26, 2024

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2021

A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases

- Anna Catharina Vieira Armond ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7121-5354 1 ,

- Bert Gordijn 2 ,

- Jonathan Lewis 2 ,

- Mohammad Hosseini 2 ,

- János Kristóf Bodnár 1 ,

- Soren Holm 3 , 4 &

- Péter Kakuk 5

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 50 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

34 Citations

29 Altmetric

Metrics details

The areas of Research Ethics (RE) and Research Integrity (RI) are rapidly evolving. Cases of research misconduct, other transgressions related to RE and RI, and forms of ethically questionable behaviors have been frequently published. The objective of this scoping review was to collect RE and RI cases, analyze their main characteristics, and discuss how these cases are represented in the scientific literature.

The search included cases involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework. A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without language or date restriction. Data relating to the articles and the cases were extracted from case descriptions.

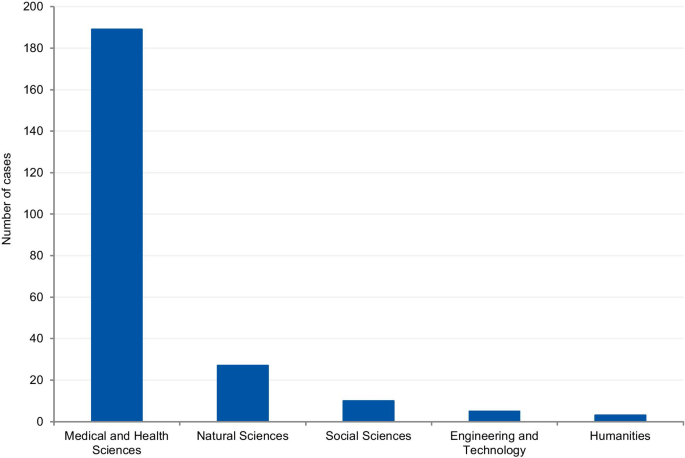

A total of 14,719 records were identified, and 388 items were included in the qualitative synthesis. The papers contained 500 case descriptions. After applying the eligibility criteria, 238 cases were included in the analysis. In the case analysis, fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%), followed by patient safety issues (11.1%) and plagiarism (6.9%). 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities. Paper retraction was the most prevalent sanction (45.4%), followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%).

Conclusions

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields compared to its proportion in scientific publications. The cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of misbehaviors. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations, and from recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Peer Review reports

There has been an increase in academic interest in research ethics (RE) and research integrity (RI) over the past decade. This is due, among other reasons, to the changing research environment with new and complex technologies, increased pressure to publish, greater competition in grant applications, increased university-industry collaborative programs, and growth in international collaborations [ 1 ]. In addition, part of the academic interest in RE and RI is due to highly publicized cases of misconduct [ 2 ].

There is a growing body of published RE and RI cases, which may contribute to public attitudes regarding both science and scientists [ 3 ]. Different approaches have been used in order to analyze RE and RI cases. Studies focusing on ORI files (Office of Research Integrity) [ 2 ], retracted papers [ 4 ], quantitative surveys [ 5 ], data audits [ 6 ], and media coverage [ 3 ] have been conducted to understand the context, causes, and consequences of these cases.

Analyses of RE and RI cases often influence policies on responsible conduct of research [ 1 ]. Moreover, details about cases facilitate a broader understanding of issues related to RE and RI and can drive interventions to address them. Currently, there are no comprehensive studies that have collected and evaluated the RE and RI cases available in the academic literature. This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE consortium to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). Two separate analyses have been conducted. The first analysis uses identified research articles to explore how the literature presents cases of RE and RI, in relation to the year of publication, country, article genre, and violation involved. The second analysis uses the cases extracted from the literature in order to characterize the cases and analyze them concerning the violations involved, sanctions, and field of science.

This scoping review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The full protocol was pre-registered and it is available at https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bde92120&appId=PPGMS .

Eligibility

Articles with non-fictional case(s) involving a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, were included. Cases unrelated to scientific activities, research institutions, academic or industrial research and publication were excluded. Articles that did not contain a substantial description of the case were also excluded.

A normative framework consists of explicit rules, formulated in laws, regulations, codes, and guidelines, as well as implicit rules, which structure local research practices and influence the application of explicitly formulated rules. Therefore, if a case involves a violation of, or misbehavior, poor judgment, or detrimental research practice in relation to a normative framework, then it does so on the basis of explicit and/or implicit rules governing RE and RI practice.

Search strategy

A search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, JSTOR, Ovid, and Science Direct in March 2018, without any language or date restrictions. Two parallel searches were performed with two sets of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms, one for RE and another for RI. The parallel searches generated two sets of data thereby enabling us to analyze and further investigate the overlaps in, differences in, and evolution of, the representation of RE and RI cases in the academic literature. The terms used in the first search were: (("research ethics") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The terms used in the parallel search were: (("research integrity") AND (violation OR unethical OR misconduct)). The search strategy’s validity was tested in a pilot search, in which different keyword combinations and search strings were used, and the abstracts of the first hundred hits in each database were read (Additional file 1 ).

After searching the databases with these two search strings, the titles and abstracts of extracted items were read by three contributors independently (ACVA, PK, and KB). Articles that could potentially meet the inclusion criteria were identified. After independent reading, the three contributors compared their results to determine which studies were to be included in the next stage. In case of a disagreement, items were reassessed in order to reach a consensus. Subsequently, qualified items were read in full.

Data extraction

Data extraction processes were divided by three assessors (ACVA, PK and KB). Each list of extracted data generated by one assessor was cross-checked by the other two. In case of any inconsistencies, the case was reassessed to reach a consensus. The following categories were employed to analyze the data of each extracted item (where available): (I) author(s); (II) title; (III) year of publication; (IV) country (according to the first author's affiliation); (V) article genre; (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification)[ 7 ]; (X) types of violation (see below); (XI) case description; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case.

Two sets of data were created after the data extraction process. One set was used for the analysis of articles and their representation in the literature, and the other set was created for the analysis of cases. In the set for the analysis of articles, all eligible items, including duplicate cases (cases found in more than one paper, e.g. Hwang case, Baltimore case) were included. The aim was to understand the historical aspects of violations reported in the literature as well as the paper genre in which cases are described and discussed. For this set, the variables of the year of publication (III); country (IV); article genre (V); and types of violation (X) were analyzed.

For the analysis of cases, all duplicated cases and cases that did not contain enough information about particularities to differentiate them from others (e.g. names of the people or institutions involved, country, date) were excluded. In this set, prominent cases (i.e. those found in more than one paper) were listed only once, generating a set containing solely unique cases. These additional exclusion criteria were applied to avoid multiple representations of cases. For the analysis of cases, the variables: (VI) year of the case; (VII) country in which the case took place; (VIII) institution(s) and person(s) involved; (IX) field of science (FOS-OECD classification); (X) types of violation; (XI) case details; and (XII) consequences for persons or institutions involved in the case were considered.

Article genre classification

We used ten categories to capture the differences in genre. We included a case description in a “news” genre if a case was published in the news section of a scientific journal or newspaper. Although we have not developed a search strategy for newspaper articles, some of them (e.g. New York Times) are indexed in scientific databases such as Pubmed. The same method was used to allocate case descriptions to “editorial”, “commentary”, “misconduct notice”, “retraction notice”, “review”, “letter” or “book review”. We applied the “case analysis” genre if a case description included a normative analysis of the case. The “educational” genre was used when a case description was incorporated to illustrate RE and RI guidelines or institutional policies.

Categorization of violations

For the extraction process, we used the articles’ own terminology when describing violations/ethical issues involved in the event (e.g. plagiarism, falsification, ghost authorship, conflict of interest, etc.) to tag each article. In case the terminology was incompatible with the case description, other categories were added to the original terminology for the same case. Subsequently, the resulting list of terms was standardized using the list of major and minor misbehaviors developed by Bouter and colleagues [ 8 ]. This list consists of 60 items classified into four categories: Study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. (Additional file 2 ).

Systematic search

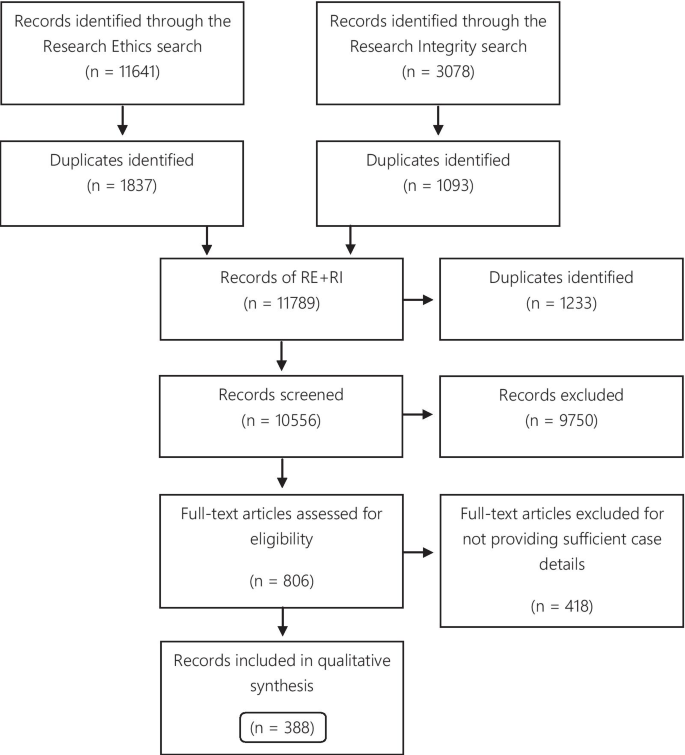

A total of 11,641 records were identified through the RE search and 3078 in the RI search. The results of the parallel searches were combined and the duplicates removed. The remaining 10,556 records were screened, and at this stage, 9750 items were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. 806 items were selected for full-text reading. Subsequently, 388 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram

Of the 388 articles, 157 were only identified via the RE search, 87 exclusively via the RI search, and 144 were identified via both search strategies. The eligible articles contained 500 case descriptions, which were used for the analysis of the publications articles analysis. 256 case descriptions discussed the same 50 cases. The Hwang case was the most frequently described case, discussed in 27 articles. Furthermore, the top 10 most described cases were found in 132 articles (Table 1 ).

For the analysis of cases, 206 (41.2% of the case descriptions) duplicates were excluded, and 56 (11.2%) cases were excluded for not providing enough information to distinguish them from other cases, resulting in 238 eligible cases.

Analysis of the articles

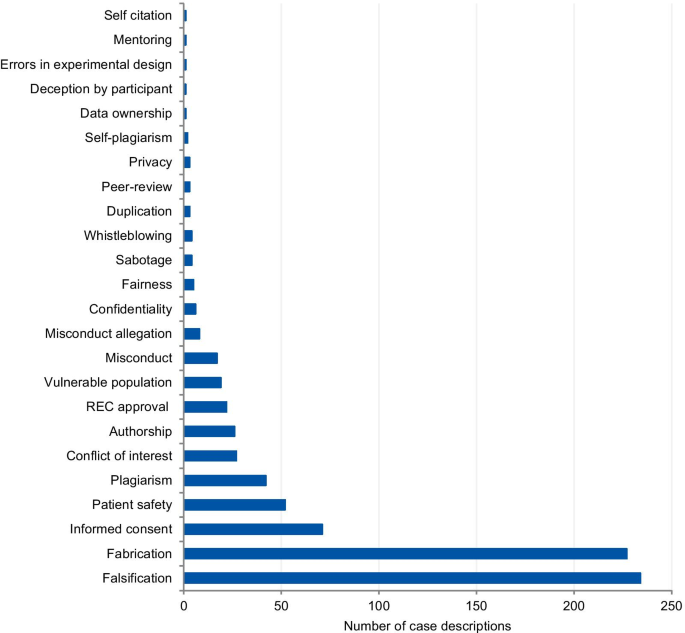

The categories used to classify the violations include those that pertain to the different kinds of scientific misconduct (falsification, fabrication, plagiarism), detrimental research practices (authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, and mentoring), and “other misconduct” (according to the definitions from the National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, [ 1 ]). Each case could involve more than one type of violation. The majority of cases presented more than one violation or ethical issue, with a mean of 1.56 violations per case. Figure 2 presents the frequency of each violation tagged to the articles. Falsification and fabrication were the most frequently tagged violations. The violations accounted respectively for 29.1% and 30.0% of the number of taggings (n = 780), and they were involved in 46.8% and 45.4% of the articles (n = 500 case descriptions). Problems with informed consent represented 9.1% of the number of taggings and 14% of the articles, followed by patient safety (6.7% and 10.4%) and plagiarism (5.4% and 8.4%). Detrimental research practices, such as authorship issues, duplication, peer-review, errors in experimental design, mentoring, and self-citation were mentioned cumulatively in 7.0% of the articles.

Tagged violations from the article analysis

Analysis of the cases

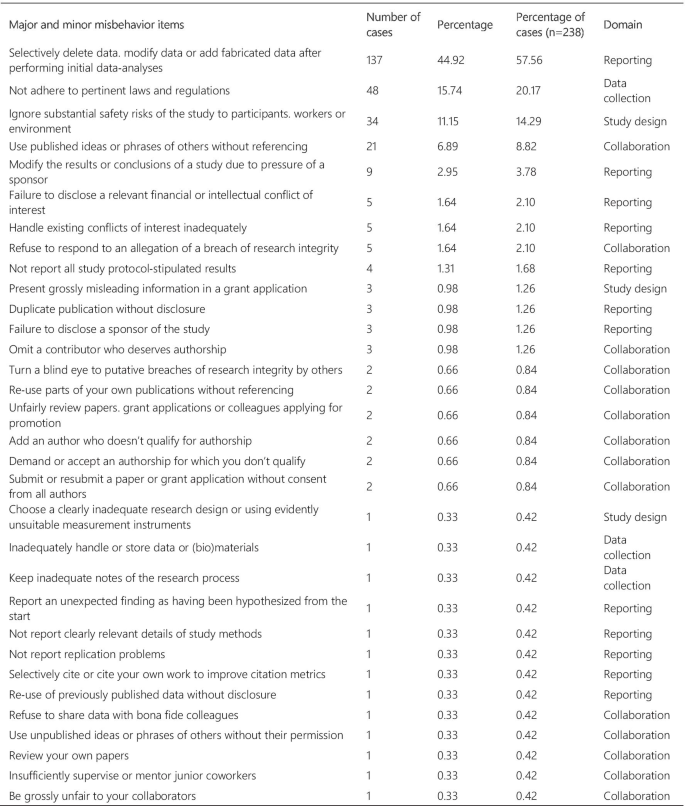

Figure 3 presents the frequency and percentage of each violation found in the cases. Each case could include more than one item from the list. The 238 cases were tagged 305 times, with a mean of 1.28 items per case. Fabrication and falsification were the most frequently tagged violations (44.9%), involved in 57.7% of the cases (n = 238). The non-adherence to pertinent laws and regulations, such as lack of informed consent and REC approval, was the second most frequently tagged violation (15.7%) and involved in 20.2% of the cases. Patient safety issues were the third most frequently tagged violations (11.1%), involved in 14.3% of the cases, followed by plagiarism (6.9% and 8.8%). The list of major and minor misbehaviors [ 8 ] classifies the items into study design, data collection, reporting, and collaboration issues. Our results show that 56.0% of the tagged violations involved issues in reporting, 16.4% in data collection, 15.1% involved collaboration issues, and 12.5% in the study design. The items in the original list that were not listed in the results were not involved in any case collected.

Major and minor misbehavior items from the analysis of cases

Article genre

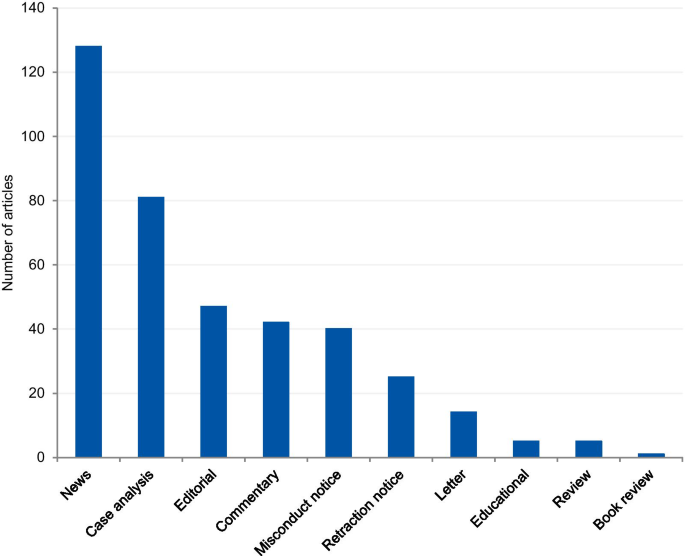

The articles were mostly classified into “news” (33.0%), followed by “case analysis” (20.9%), “editorial” (12.1%), “commentary” (10.8%), “misconduct notice” (10.3%), “retraction notice” (6.4%), “letter” (3.6%), “educational paper” (1.3%), “review” (1%), and “book review” (0.3%) (Fig. 4 ). The articles classified into “news” and “case analysis” included predominantly prominent cases. Items classified into “news” often explored all the investigation findings step by step for the associated cases as the case progressed through investigations, and this might explain its high prevalence. The case analyses included mainly normative assessments of prominent cases. The misconduct and retraction notices included the largest number of unique cases, although a relatively large portion of the retraction and misconduct records could not be included because of insufficient case details. The articles classified into “editorial”, “commentary” and “letter” also included unique cases.

Article genre of included articles

Article analysis

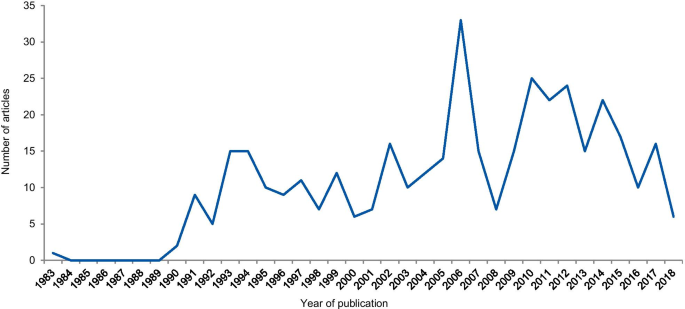

The dates of the eligible articles range from 1983 to 2018 with notable peaks between 1990 and 1996, most probably associated with the Gallo [ 9 ] and Imanishi-Kari cases [ 10 ], and around 2005 with the Hwang [ 11 ], Wakefield [ 12 ], and CNEP trial cases [ 13 ] (Fig. 5 ). The trend line shows an increase in the number of articles over the years.

Frequency of articles according to the year of publication

Case analysis

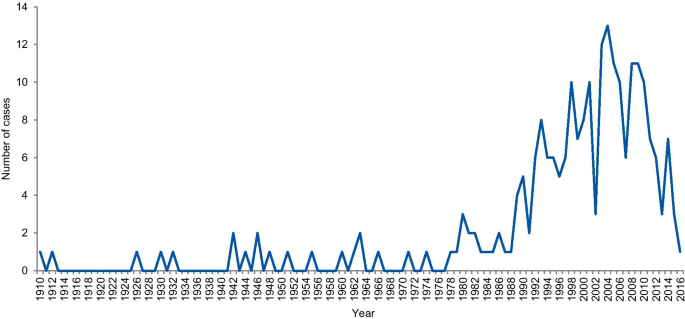

The dates of included cases range from 1798 to 2016. Two cases occurred before 1910, one in 1798 and the other in 1845. Figure 6 shows the number of cases per year from 1910. An increase in the curve started in the early 1980s, reaching the highest frequency in 2004 with 13 cases.

Frequency of cases per year

Geographical distribution

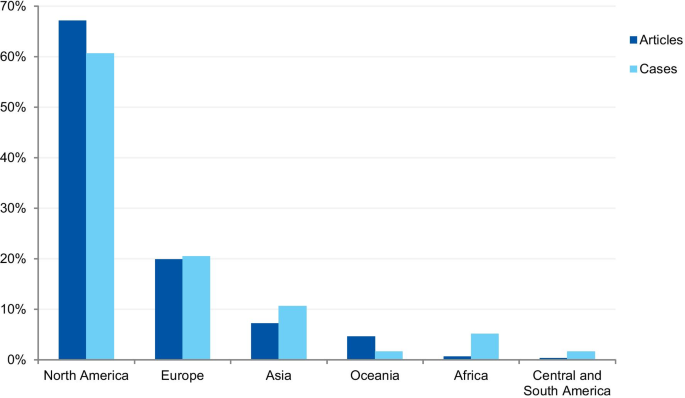

The first analysis concerned the authors’ affiliation and the corresponding author’s address. Where the article contained more than one country in the affiliation list, only the first author’s location was considered. Eighty-one articles were excluded because the authors’ affiliations were not available, and 307 articles were included in the analysis. The articles originated from 26 different countries (Additional file 3 ). Most of the articles emanated from the USA and the UK (61.9% and 14.3% of articles, respectively), followed by Canada (4.9%), Australia (3.3%), China (1.6%), Japan (1.6%), Korea (1.3%), and New Zealand (1.3%). Some of the most discussed cases occurred in the USA; the Imanishi-Kari, Gallo, and Schön cases [ 9 , 10 ]. Intensely discussed cases are also associated with Canada (Fisher/Poisson and Olivieri cases), the UK (Wakefield and CNEP trial cases), South Korea (Hwang case), and Japan (RIKEN case) [ 12 , 14 ]. In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of articles (Fig. 7 ).

Percentage of articles and cases by continent

The case analysis involved the location where the case took place, taking into account the institutions involved in the case. For cases involving more than one country, all the countries were considered. Three cases were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient information. In the case analysis, 40 countries were involved in 235 different cases (Additional file 4 ). Our findings show that most of the reported cases occurred in the USA and the United Kingdom (59.6% and 9.8% of cases, respectively). In addition, a number of cases occurred in Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), China (2.1%), and Germany (2.1%). In terms of percentages, North America and Europe stand out in the number of cases (Fig. 7 ). To enable comparison, we have additionally collected the number of published documents according to country distribution, available on SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ]. The numbers correspond to the documents published from 1996 to 2019. The USA occupies the first place in the number of documents, with 21.9%, followed by China (11.1%), UK (6.3%), Germany (5.5%), and Japan (4.9%).

Field of science

The cases were classified according to the field of science. Four cases (1.7%) could not be classified due to insufficient information. Where information was available, 80.8% of cases were from the Medical and Health Sciences, 11.5% from the Natural Sciences, 4.3% from Social Sciences, 2.1% from Engineering and Technology, and 1.3% from Humanities (Fig. 8 ). Additionally, we have retrieved the number of published documents according to scientific field distribution, available on SCImago [ 16 ]. Of the total number of scientific publications, 41.5% are related to natural sciences, 22% to engineering, 25.1% to health and medical sciences, 7.8% to social sciences, 1.9% to agricultural sciences, and 1.7% to the humanities.

Field of science from the analysis of cases

This variable aimed to collect information on possible consequences and sanctions imposed by funding agencies, scientific journals and/or institutions. 97 cases could not be classified due to insufficient information. 141 cases were included. Each case could potentially include more than one outcome. Most of cases (45.4%) involved paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications (35.5%). (Table 2 ).

RE and RI cases have been increasingly discussed publicly, affecting public attitudes towards scientists and raising awareness about ethical issues, violations, and their wider consequences [ 5 ]. Different approaches have been applied in order to quantify and address research misbehaviors [ 5 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. However, most cases are investigated confidentially and the findings remain undisclosed even after the investigation [ 19 , 20 ]. Therefore, the study aimed to collect the RE and RI cases available in the scientific literature, understand how the cases are discussed, and identify the potential of case descriptions to raise awareness on RE and RI.

We collected and analyzed 500 detailed case descriptions from 388 articles and our results show that they mostly relate to extensively discussed and notorious cases. Approximately half of all included cases was mentioned in at least two different articles, and the top ten most commonly mentioned cases were discussed in 132 articles.

The prominence of certain cases in the literature, based on the number of duplicated cases we found (e.g. Hwang case), can be explained by the type of article in which cases are discussed and the type of violation involved in the case. In the article genre analysis, 33% of the cases were described in the news section of scientific publications. Our findings show that almost all article genres discuss those cases that are new and in vogue. Once the case appears in the public domain, it is intensely discussed in the media and by scientists, and some prominent cases have been discussed for more than 20 years (Table 1 ). Misconduct and retraction notices were exceptions in the article genre analysis, as they presented mostly unique cases. The misconduct notices were mainly found on the NIH repository, which is indexed in the searched databases. Some federal funding agencies like NIH usually publicize investigation findings associated with the research they fund. The results derived from the NIH repository also explains the large proportion of articles from the US (61.9%). However, in some cases, only a few details are provided about the case. For cases that have not received federal funding and have not been reported to federal authorities, the investigation is conducted by local institutions. In such instances, the reporting of findings depends on each institution’s policy and willingness to disclose information [ 21 ]. The other exception involves retraction notices. Despite the existence of ethical guidelines [ 22 ], there is no uniform and a common approach to how a journal should report a retraction. The Retraction Watch website suggests two lists of information that should be included in a retraction notice to satisfy the minimum and optimum requirements [ 22 , 23 ]. As well as disclosing the reason for the retraction and information regarding the retraction process, optimal notices should include: (I) the date when the journal was first alerted to potential problems; (II) details regarding institutional investigations and associated outcomes; (III) the effects on other papers published by the same authors; (IV) statements about more recent replications only if and when these have been validated by a third party; (V) details regarding the journal’s sanctions; and (VI) details regarding any lawsuits that have been filed regarding the case. The lack of transparency and information in retraction notices was also noted in studies that collected and evaluated retractions [ 24 ]. According to Resnik and Dinse [ 25 ], retractions notices related to cases of misconduct tend to avoid naming the specific violation involved in the case. This study found that only 32.8% of the notices identify the actual problem, such as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, and 58.8% reported the case as replication failure, loss of data, or error. Potential explanations for euphemisms and vague claims in retraction notices authored by editors could pertain to the possibility of legal actions from the authors, honest or self-reported errors, and lack of resources to conduct thorough investigations. In addition, the lack of transparency can also be explained by the conflicts of interests of the article’s author(s), since the notices are often written by the authors of the retracted article.

The analysis of violations/ethical issues shows the dominance of fabrication and falsification cases and explains the high prevalence of prominent cases. Non-adherence to laws and regulations (REC approval, informed consent, and data protection) was the second most prevalent issue, followed by patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. The prevalence of the five most tagged violations in the case analysis was higher than the prevalence found in the analysis of articles that involved the same violations. The only exceptions are fabrication and falsification cases, which represented 45% of the tagged violations in the analysis of cases, and 59.1% in the article analysis. This disproportion shows a predilection for the publication of discussions related to fabrication and falsification when compared to other serious violations. Complex cases involving these types of violations make good headlines and this follows a custom pattern of writing about cases that catch the public and media’s attention [ 26 ]. The way cases of RE and RI violations are explored in the literature gives a sense that only a few scientists are “the bad apples” and they are usually discovered, investigated, and sanctioned accordingly. This implies that the integrity of science, in general, remains relatively untouched by these violations. However, studies on misconduct determinants show that scientific misconduct is a systemic problem, which involves not only individual factors, but structural and institutional factors as well, and that a combined effort is necessary to change this scenario [ 27 , 28 ].

Analysis of cases

A notable increase in RE and RI cases occurred in the 1990s, with a gradual increase until approximately 2006. This result is in agreement with studies that evaluated paper retractions [ 24 , 29 ]. Although our study did not focus only on retractions, the trend is similar. This increase in cases should not be attributed only to the increase in the number of publications, since studies that evaluated retractions show that the percentage of retraction due to fraud has increased almost ten times since 1975, compared to the total number of articles. Our results also show a gradual reduction in the number of cases from 2011 and a greater drop in 2015. However, this reduction should be considered cautiously because many investigations take years to complete and have their findings disclosed. ORI has shown that from 2001 to 2010 the investigation of their cases took an average of 20.48 months with a maximum investigation time of more than 9 years [ 24 ].

The countries from which most cases were reported were the USA (59.6%), the UK (9.8%), Canada (6.0%), Japan (5.5%), and China (2.1%). When analyzed by continent, the highest percentage of cases took place in North America, followed by Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa. The predominance of cases from the USA is predictable, since the country publishes more scientific articles than any other country, with 21.8% of the total documents, according to SCImago [ 16 ]. However, the same interpretation does not apply to China, which occupies the second position in the ranking, with 11.2%. These differences in the geographical distribution were also found in a study that collected published research on research integrity [ 30 ]. The results found by Aubert Bonn and Pinxten (2019) show that studies in the United States accounted for more than half of the sample collected, and although China is one of the leaders in scientific publications, it represented only 0.7% of the sample. Our findings can also be explained by the search strategy that included only keywords in English. Since the majority of RE and RI cases are investigated and have their findings locally disclosed, the employment of English keywords and terms in the search strategy is a limitation. Moreover, our findings do not allow us to draw inferences regarding the incidence or prevalence of misconduct around the world. Instead, it shows where there is a culture of publicly disclosing information and openly discussing RE and RI cases in English documents.

Scientific field analysis

The results show that 80.8% of reported cases occurred in the medical and health sciences whilst only 1.3% occurred in the humanities. This disciplinary difference has also been observed in studies on research integrity climates. A study conducted by Haven and colleagues, [ 28 ] associated seven subscales of research climate with the disciplinary field. The subscales included: (1) Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) resources, (2) regulatory quality, (3) integrity norms, (4) integrity socialization, (5) supervisor/supervisee relations, (6) (lack of) integrity inhibitors, and (7) expectations. The results, based on the seven subscale scores, show that researchers from the humanities and social sciences have the lowest perception of the RI climate. By contrast, the natural sciences expressed the highest perception of the RI climate, followed by the biomedical sciences. There are also significant differences in the depth and extent of the regulatory environments of different disciplines (e.g. the existence of laws, codes of conduct, policies, relevant ethics committees, or authorities). These findings corroborate our results, as those areas of science most familiar with RI tend to explore the subject further, and, consequently, are more likely to publish case details. Although the volume of published research in each research area also influences the number of cases, the predominance of medical and health sciences cases is not aligned with the trends regarding the volume of published research. According to SCImago Journal & Country Rank [ 16 ], natural sciences occupy the first place in the number of publications (41,5%), followed by the medical and health sciences (25,1%), engineering (22%), social sciences (7,8%), and the humanities (1,7%). Moreover, biomedical journals are overrepresented in the top scientific journals by IF ranking, and these journals usually have clear policies for research misconduct. High-impact journals are more likely to have higher visibility and scrutiny, and consequently, more likely to have been the subject of misconduct investigations. Additionally, the most well-known general medical journals, including NEJM, The Lancet, and the BMJ, employ journalists to write their news sections. Since these journals have the resources to produce extensive news sections, it is, therefore, more likely that medical cases will be discussed.

Violations analysis

In the analysis of violations, the cases were categorized into major and minor misbehaviors. Most cases involved data fabrication and falsification, followed by cases involving non-adherence to laws and regulations, patient safety, plagiarism, and conflicts of interest. When classified by categories, 12.5% of the tagged violations involved issues in the study design, 16.4% in data collection, 56.0% in reporting, and 15.1% involved collaboration issues. Approximately 80% of the tagged violations involved serious research misbehaviors, based on the ranking of research misbehaviors proposed by Bouter and colleagues. However, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Fanelli (2009), most self-declared cases involve questionable research practices. In the meta-analysis, 33.7% of scientists admitted questionable research practices, and 72% admitted when asked about the behavior of colleagues. This finding contrasts with an admission rate of 1.97% and 14.12% for cases involving fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism. However, Fanelli’s meta-analysis does not include data about research misbehaviors in its wider sense but focuses on behaviors that bias research results (i.e. fabrication and falsification, intentional non-publication of results, biased methodology, misleading reporting). In our study, the majority of cases involved FFP (66.4%). Overrepresentation of some types of violations, and underrepresentation of others, might lead to misguided efforts, as cases that receive intense publicity eventually influence policies relating to scientific misconduct and RI [ 20 ].

Sanctions analysis

The five most prevalent outcomes were paper retraction, followed by exclusion from funding applications, exclusion from service or position, dismissal and suspension, and paper correction. This result is similar to that found by Redman and Merz [ 31 ], who collected data from misconduct cases provided by the ORI. Moreover, their results show that fabrication and falsification cases are 8.8 times more likely than others to receive funding exclusions. Such cases also received, on average, 0.6 more sanctions per case. Punishments for misconduct remain under discussion, ranging from the criminalization of more serious forms of misconduct [ 32 ] to social punishments, such as those recently introduced by China [ 33 ]. The most common sanction identified by our analysis—paper retraction—is consistent with the most prevalent types of violation, that is, falsification and fabrication.

Publicizing scientific misconduct

The lack of publicly available summaries of misconduct investigations makes it difficult to share experiences and evaluate the effectiveness of policies and training programs. Publicizing scientific misconduct can have serious consequences and creates a stigma around those involved in the case. For instance, publicized allegations can damage the reputation of the accused even when they are later exonerated [ 21 ]. Thus, for published cases, it is the responsibility of the authors and editors to determine whether the name(s) of those involved should be disclosed. On the one hand, it is envisaged that disclosing the name(s) of those involved will encourage others in the community to foster good standards. On the other hand, it is suggested that someone who has made a mistake should have the right to a chance to defend his/her reputation. Regardless of whether a person's name is left out or disclosed, case reports have an important educational function and can help guide RE- and RI-related policies [ 34 ]. A recent paper published by Gunsalus [ 35 ] proposes a three-part approach to strengthen transparency in misconduct investigations. The first part consists of a checklist [ 36 ]. The second suggests that an external peer reviewer should be involved in investigative reporting. The third part calls for the publication of the peer reviewer’s findings.

Limitations

One of the possible limitations of our study may be our search strategy. Although we have conducted pilot searches and sensitivity tests to reach the most feasible and precise search strategy, we cannot exclude the possibility of having missed important cases. Furthermore, the use of English keywords was another limitation of our search. Since most investigations are performed locally and published in local repositories, our search only allowed us to access cases from English-speaking countries or discussed in academic publications written in English. Additionally, it is important to note that the published cases are not representative of all instances of misconduct, since most of them are never discovered, and when discovered, not all are fully investigated or have their findings published. It is also important to note that the lack of information from the extracted case descriptions is a limitation that affects the interpretation of our results. In our review, only 25 retraction notices contained sufficient information that allowed us to include them in our analysis in conformance with the inclusion criteria. Although our search strategy was not focused specifically on retraction and misconduct notices, we believe that if sufficiently detailed information was available in such notices, the search strategy would have identified them.

Case descriptions found in academic journals are dominated by discussions regarding prominent cases and are mainly published in the news section of journals. Our results show that there is an overrepresentation of biomedical research cases over other scientific fields when compared with the volume of publications produced by each field. Moreover, published cases mostly involve fabrication, falsification, and patient safety issues. This finding could have a significant impact on the academic representation of ethical issues for RE and RI. The predominance of fabrication and falsification cases might diverge the attention of the academic community from relevant but less visible violations and ethical issues, and recently emerging forms of misbehaviors.

Availability of data and materials

This review has been developed by members of the EnTIRE project in order to generate information on the cases that will be made available on the Embassy of Good Science platform ( www.embassy.science ). The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository in https://osf.io/3xatj/?view_only=313a0477ab554b7489ee52d3046398b9 .

National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Fostering integrity in research. National Academies Press; 2017.

Davis MS, Riske-Morris M, Diaz SR. Causal factors implicated in research misconduct: evidence from ORI case files. Sci Eng Ethics. 2007;13(4):395–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-007-9045-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Ampollini I, Bucchi M. When public discourse mirrors academic debate: research integrity in the media. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020;26(1):451–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00103-5 .

Hesselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M. The visibility of scientific misconduct: a review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Curr Sociol La Sociologie contemporaine. 2017;65(6):814–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116663807 .

Martinson BC, Anderson MS, de Vries R. Scientists behaving badly. Nature. 2005;435(7043):737–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/435737a .

Loikith L, Bauchwitz R. The essential need for research misconduct allegation audits. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(4):1027–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9798-6 .

OECD. Revised field of science and technology (FoS) classification in the Frascati manual. Working Party of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators 2007. p. 1–12.

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integrity Peer Rev. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 .

Greenberg DS. Resounding echoes of Gallo case. Lancet. 1995;345(8950):639.

Dresser R. Giving scientists their due. The Imanishi-Kari decision. Hastings Center Rep. 1997;27(3):26–8.

Hong ST. We should not forget lessons learned from the Woo Suk Hwang’s case of research misconduct and bioethics law violation. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(11):1671–2. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.11.1671 .

Opel DJ, Diekema DS, Marcuse EK. Assuring research integrity in the wake of Wakefield. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342(7790):179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2 .

Wells F. The Stoke CNEP Saga: did it need to take so long? J R Soc Med. 2010;103(9):352–6. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k010 .

Normile D. RIKEN panel finds misconduct in controversial paper. Science. 2014;344(6179):23. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.344.6179.23 .

Wager E. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE): Objectives and achievements 1997–2012. La Presse Médicale. 2012;41(9):861–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lpm.2012.02.049 .

SCImago nd. SJR — SCImago Journal & Country Rank [Portal]. http://www.scimagojr.com . Accessed 03 Feb 2021.

Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738 .

Steneck NH. Fostering integrity in research: definitions, current knowledge, and future directions. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12(1):53–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00022268 .

DuBois JM, Anderson EE, Chibnall J, Carroll K, Gibb T, Ogbuka C, et al. Understanding research misconduct: a comparative analysis of 120 cases of professional wrongdoing. Account Res. 2013;20(5–6):320–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822248 .

National Academy of Sciences NAoE, Institute of Medicine Panel on Scientific R, the Conduct of R. Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process: Volume I. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright (c) 1992 by the National Academy of Sciences; 1992.

Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Flanagin A, Thornton J. Scientific misconduct and medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1985–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14350 .

COPE Council. COPE Guidelines: Retraction Guidelines. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24318/cope.2019.1.4 .

Retraction Watch. What should an ideal retraction notice look like? 2015, May 21. https://retractionwatch.com/2015/05/21/what-should-an-ideal-retraction-notice-look-like/ .

Fang FC, Steen RG, Casadevall A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(42):17028–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109 .

Resnik DB, Dinse GE. Scientific retractions and corrections related to misconduct findings. J Med Ethics. 2013;39(1):46–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2012-100766 .

de Vries R, Anderson MS, Martinson BC. Normal misbehavior: scientists talk about the ethics of research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics JERHRE. 2006;1(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43 .

Sovacool BK. Exploring scientific misconduct: isolated individuals, impure institutions, or an inevitable idiom of modern science? J Bioethical Inquiry. 2008;5(4):271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9113-6 .

Haven TL, Tijdink JK, Martinson BC, Bouter LM. Perceptions of research integrity climate differ between academic ranks and disciplinary fields: results from a survey among academic researchers in Amsterdam. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210599 .

Trikalinos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Falsified papers in high-impact journals were slow to retract and indistinguishable from nonfraudulent papers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(5):464–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.019 .

Aubert Bonn N, Pinxten W. A decade of empirical research on research integrity: What have we (not) looked at? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(4):338–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619858534 .

Redman BK, Merz JF. Scientific misconduct: do the punishments fit the crime? Science. 2008;321(5890):775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158052 .

Bülow W, Helgesson G. Criminalization of scientific misconduct. Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22(2):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-018-9865-7 .

Cyranoski D. China introduces “social” punishments for scientific misconduct. Nature. 2018;564(7736):312. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07740-z .

Bird SJ. Publicizing scientific misconduct and its consequences. Sci Eng Ethics. 2004;10(3):435–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-004-0001-0 .

Gunsalus CK. Make reports of research misconduct public. Nature. 2019;570(7759):7. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01728-z .

Gunsalus CK, Marcus AR, Oransky I. Institutional research misconduct reports need more credibility. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1315–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0358 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the EnTIRE research group. The EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) aims to create an online platform that makes RE+RI information easily accessible to the research community. The EnTIRE Consortium is composed by VU Medical Center, Amsterdam, gesinn. It Gmbh & Co Kg, KU Leuven, University of Split School of Medicine, Dublin City University, Central European University, University of Oslo, University of Manchester, European Network of Research Ethics Committees.

EnTIRE project (Mapping Normative Frameworks for Ethics and Integrity of Research) has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement N 741782. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Móricz Zsigmond krt. 22. III. Apartman Diákszálló, Debrecen, 4032, Hungary

Anna Catharina Vieira Armond & János Kristóf Bodnár

Institute of Ethics, School of Theology, Philosophy and Music, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

Bert Gordijn, Jonathan Lewis & Mohammad Hosseini

Centre for Social Ethics and Policy, School of Law, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Center for Medical Ethics, HELSAM, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary

Péter Kakuk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors (ACVA, BG, JL, MH, JKB, SH and PK) developed the idea for the article. ACVA, PK, JKB performed the literature search and data analysis, ACVA and PK produced the draft, and all authors critically revised it. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna Catharina Vieira Armond .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Pilot search and search strategy.

Additional file 2

. List of Major and minor misbehavior items (Developed by Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Research integrity and peer review. 2016;1(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0024-5 ).

Additional file 3

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of articles.

Additional file 4

. Table containing the number and percentage of countries included in the analysis of the cases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Armond, A.C.V., Gordijn, B., Lewis, J. et al. A scoping review of the literature featuring research ethics and research integrity cases. BMC Med Ethics 22 , 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2020

Accepted : 21 April 2021

Published : 30 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00620-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Research ethics

- Research integrity

- Scientific misconduct

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A review of the current concerns about misconduct in medical sciences publications and the consequences

Taraneh mousavi, mohammad abdollahi.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Dec 17; Accepted 2020 Jan 31; Collection date 2020 Jun.

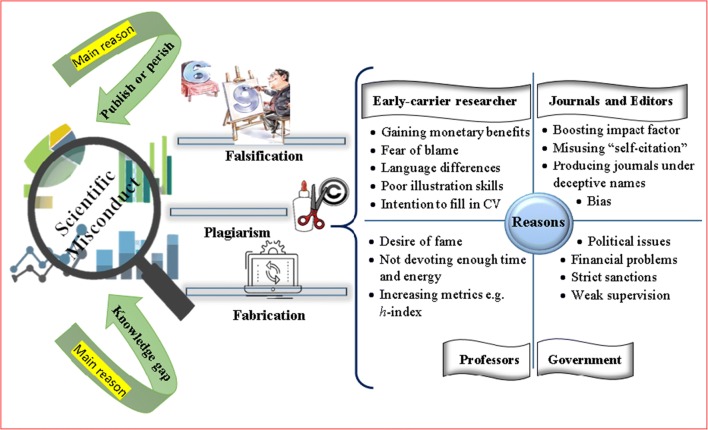

In the new era of publication, scientific misconduct has become a focus of concern including extreme variability of plagiarism, falsification, fabrication, authorship issues, peer review manipulation, etc. Along with, overarching theme of “retraction” and “predatory journals” have emphasized the importance of studying related infrastructures.

Information used in this review was provided through accessing various databases as Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Nature Index, Publication Ethics and Retraction Watch. Original researches, expert opinions, comments, letters, editorials, books mostly published between 2010 and 2020 were gathered and categorized into three sections of “Common types of misconduct”,” Reasons behind scientific misconduct” and “Consequences”. Within each part, remarkable examples from the past 10 years cited in Retraction Watch are indicated. At last, possible solution on combating misconduct are suggested.

The number of publications are on the dramatic rise fostering a competition under which scholars are pushed to publish more. Consequently, due to several reasons including poor linguistic and illustration skills, not adequate evaluation, limited experience, etc. researchers might tend toward misbehavior endangering the health facts and ultimately, eroding country, journal/publisher, and perpetrator’s creditability. The reported incident seems to be enhanced by the emergence of predatory with publishing about 8 times more papers in 2014 than which is in 2010. So that today, 65.3% of paper retraction is solely attributing to misconduct, with plagiarism at the forefront. As well, authorship issues and peer-review manipulation are found to have significant contribution besides further types of misconduct in this duration.

Given the expansion of the academic competitive environment and with the increase in research misconduct, the role of any regulatory sector, including universities, journals/publishers, government, etc. in preventing this phenomenon must be fully focused and fundamental alternation should be implemented in this regard.

Keywords: Misconduct, Medical sciences, Publications, Consequences

Introduction

Over the past decade, the total documentation of solely 233 top global countries contained in Scopus database has increased from 2,771,765 in 2010 to approximately 4 million in 2018 according to SCImago Institutions Rankings (SIR) [ 1 ] . Along with, a trend of “hyper authorship” or “mass authorship”, writing articles with more than 1000 co-authors, have increased about 2-fold over five past years [ 2 ]. These increments, more than other factors, is attributable to the significant rise in the number of universities, researchers and accordingly fostering a hypercompetitive environment in which publishing more articles or having higher metrics are told to be the only way of being successful. While it can be said that such atmosphere is beneficial for science growth, one must always keep in mind what are the detrimental consequences if there is improper academic evaluation; for instance easier entrance exam, inadequate supervision on professors performance, and paying more attention to personal desires including gaining scholarships, grants, carrier promotion, fame, and monetary benefits [ 3 , 4 ]. Going one step further, the undue attention to bibliometric used globally fosters this atmosphere within exerting unintended effects from negligible academic bullying (insulting, mistreating, embracing, humiliating) to more notably holding a place in employing or promoting professors because of higher metrics indices or pushing students to publish more articles deprived of practical application [ 5 , 6 ]. Indeed, today’s development of such questionable criteria may be rooted from lower academic levels where the precedence over average/scores for decision making or rewarding, teach students to cheat or make teachers to not anymore focus on the final goal of improving students’ knowledge [ 7 ]. So, it is not surprising then that lack of researcher’s knowledge from early stages, coupled with high academic pressure and innate desire to be outrank ultimately become a bullet firing research integrity and resultantly exerting detrimental effects of unethical principles so called “scientific misconduct” or “research fraudulence”. Existence of scientific misconduct in the field of medical sciences has shown to inflict very severe blows to the individual and public health; highlighting the immediate need of solution finding.

Thus, to help out meeting this challenge, this article begins with giving the definition and more recent types of research misconduct at the current, followed by providing a complete explanation on both reasons and consequences through remarkable examples and lastly offering possible solutions by addressing globally accepted guidelines. As far as we know, there is no similar study in the past decade with categorizing the contributory factors and outcomes in a detailed way. This is the first study in its kind focusing on the most recent top cases of misconduct, all can be served as a lesson for current researchers and be valuable to secure the future of research integrity.

Information used in this review was provided through accessing various databases as Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Nature Index, Publication Ethics and Retraction Watch. Searched terms mostly include “Scientific Misconduct”, “Misconduct in Research”, “Types of Misconduct in Research”, “Consequences of Scientific Misconduct”, “Global Burden of Publications and Misconduct” and many others. Original researches, expert opinions, comments, letters, editorials, books mostly published between 2010 and 2020 were also gathered and addressed.

Misconduct and common types

Scientific misconduct is a growing phenomenon defined as “fabrication, falsification or plagiarism in proposing, performing or reviewing research or in reporting research” according to the US Office of Research Integrity. By the other terms, the types of misconduct are, but not limited to, “FFP” standing for fabrication (reporting non-observed results), falsification (manipulating data or material) and plagiarism (the act of utilizing someone else’s statement, idea, methods or results without permission) [ 8 , 9 ] including salami-slicing, picture manipulation, self-plagiarism and text recycling; all defined in Table 1 . As an example, in 2019, plagiarism detection company disclosed that of about 4 million Russian-language studies, 70,000 were republished from 2 to 17 times, mostly owing to self-plagiarism [ 10 ].

Most common types of research misconduct

More broadly, other types of misconduct i.e. authorship issues mainly “Guest Authorship”,“Gift Authorship” and “Ghost Authorship” and peer review manipulation have undergone a substantial expansion in developing and sanctioned countries possibly due the to restriction in publication [ 8 ]. In 2015, Springer Nature retracted 58 papers all containing authorship issues and peer review manipulation and 70% of which were due to plagiarism. The same experiment by BioMed Central revealed that peer-review manipulation accounted for 57%, plagiarism for 93% and authorship manipulation was a reason for all of retractions [ 11 ]. In the respect of authorship issues, ghost authorship is indicated in two different ways; first, senior researchers list those who had little or no cooperation with main author, like cases reported from the South Korea who write the name of the school-aged children as co-authors to increase the chance of university admissions [ 3 , 12 , 13 ]. Second, removing one’s name from the list of authors despite being contributed [ 14 ]. Guest authorship is also about fraudsters who abuse the name of famous researcher as co-author or corresponding author with the aim of increasing the chance of publication while the researcher has had no contribution [ 15 ]. As a report, a group of researchers did fake submission through using the prominent Dutch economist to ease acceptance. Interestingly, after questioning the editors, his name was removed in manuscript revision, saying he no longer wants to be among the author, however this attempt failed and the article was retracted due to the issue of guest authorship [ 16 ].

Compromising of peer-review integrity is of another type that has been coming to the fore in recent years. In 2012, a group of researchers used fake Elsevier Editorial System (EES) account, created a positive report from a fictional well-known referee hence mislead the editor [ 17 ]. Similar to this, a researcher lost 24 of his paper solely due to using fake email address and doing his own peer-review [ 18 ]. In 2015, BioMed Central (BMC) also removed 43 papers for fake reviews, mostly conducted by third party agencies providing fabricated details of potential peer-reviewers [ 19 ].

Unfortunately, greed for fame causes some peer reviewer to reject manuscript, steal and republish them under their own name. For instance, a submitted manuscript to Multimedia Tools and Applications (MTAP) that was under review for about 13 months with final rejection, was thoroughly plagiarized and republished days after by reviewer of the rejected manuscript, which is about peer review manipulation [ 20 ].

Bias, gender discrimination in particular, is another today’s issue on peer review process affecting submissions by female as corresponding author/first author to be more rejected even without providing peer review; which is revealed by the institute of physic (IOP) and the journal eLife , although it is hard to believe. One more analysis in 2018 by Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) also demonstrated that 25.6% and 34.2% of all rejected papers without peer review are one’s submitted by women as corresponding author or first author in respect [ 21 ]. Of note, in the current era with political issues, regional bias exists as well which makes some peer reviewers to not handle manuscript from sanctioned countries. This concern will be more discussed in the following section.

Reasons behind scientific misconduct

Main reasons: “publish or perish” and “a gap in knowledge”.

Today we face with the avalanche of admissions to university, growing number of researchers and resultantly the added pressure on academic environment, all strongly emphasize the contribution of the traditional culture of “publish or perish” in misconduct. Publish or Perish means there is a high pressure on scholars desiring for success to publish more articles in a very short duration otherwise there is no place for them in the academic competitive environment. One influential factor in this extent is the importance of articles quantity and metrics rather than quality in nowadays research which has made publishing compulsory. For instance, sometimes we see somebody publishes several articles just in a month or students aiming to secure their position/improve their CVs, rather than paying attention to effective learning, waste more time writing worthlessness articles [ 5 ]. Then, what could be the reason and outcomes of these except that one has violated authorship issues or will employ misconduct? [ 23 , 24 ]

Besides the culture of Publish or Perish, there is another reason behind scientific misconduct with the rapid advent which is the issue of “A Gap in Knowledge” appearing either in the shape of lacking linguistic, illustration or scientific skills.

On the other terms, some researchers, mostly undergraduates, often insist on authoring more papers so as to add a line to their CVs and obtain scholarships. However, in some cases, they may generally lack enough scientific and lingual information which could be later problematic and cause misinterpretation [ 8 ]. The recent incident occurs more in developing countries including China, Malaysia, Mexico, Taiwan, and Pakistan according to reports [ 8 , 25 ]. As a main reason, non-native-English-speaking authors are contributing who might misunderstand the subject, thus either declare mistaken perception or copy the statements without having permission or including references. Moreover, the challenge of “linguistic interference” and/or “poor illustration skills” that are rooted from not passing the relevant courses, place major restriction on authors asked to write review articles or editorials by way of expressing the similar idea in different words [ 26 ]. By the same token, the abuse of the language differences, may end in additional fraudulence where a researcher translate non-English texts (for example especially Chinese) into English and republish under his/her own names [ 4 ].

Other reasons

Senior researchers.

The reasons behind scientific misconduct are not limited to reported factors as it can attribute to masters whom themselves carry out unreliable studies and/or persuade others into it.

In this respect, the matter of “bias” causes some supervisors to compare their student’s results with prior successful ones and lay the blame if they are not encouraging enough. Thus the intention to publish more along with fear of blame, make academics start data alternation and selectively report the supporting outcomes which is referred to as “cooking” or “suppression” [ 9 ]. Here, authorship issues, guest authorship in particular, may also be raised when supervisors don’t devote adequate energy and time to the work under their direction and set early researchers to do it alone [ 23 ]. Aside from, high pressure in academic environment may lead masters to get more exhausted, frustrated and greedy for carrier promotion and research grants accompanied by higher metrics (i.e. number of articles, citations, etc.). The lack of proper monitoring or available working reports, then, let masters easily employ academic bullying like insulting, mistreating, embracing and humiliating, altogether result in a sense of fear particularly among undergraduates and push them toward unethical principles to gain satisfactory outcomes [ 6 ]. Quite the reverse, there are supervisors who find punishing and exposing offenses contrary to ethical values and always offer fraudsters forgiveness. This exemplary behavior, rooting from the cultural belief, not allows the wrongdoer to learn from his/her mistake, hence one may continue doing unethical principles [ 23 ].

Digital publishing is of another aspect of provoking misconduct where profitable individuals take every opportunities and start predatory printing to set researchers (esp. undergraduates) up [ 4 ]. These fraudsters, at the expense of the authors (called article processing charges, or APCs) print articles in fake journals without necessary proper checking the quality and not providing edition services [ 4 , 27 – 30 ]. A study in 2017 suggested that some journals are willing to include the names of researchers seeking for a carrier promotion in manuscript revisions for a fee and by paying more, researchers can even be introduced as a journal editor [ 31 , 32 ]. Nevertheless, a very recent research on 250 predatory journals implied that although the amount of papers published in predatory journals have increased about 8 times within 2010 to 2014, they seem to barely question the accuracy of research. Forasmuch as 59.6% of papers published in such journals have no citation and just around 2.8% cited more than 11 times limited to 32 citation at most [ 33 ].

Along with fake publication, fraudsters sometimes start naming their journals under the deceptive titles like “international” or “world” [ 4 ] or manipulating journal impact factor (IF) through exploiting excessive “self-citation” or planned citations from sister journals [ 9 , 34 ]. As well, some invalid journals only publish articles containing positive outcomes [ 27 ] or that are in the title of “novel” so that researchers are forced to report negative data and employ suppression. Taking collectively, after a short while, obscure journals will reach to an upper position, even around 18 ranks [ 9 ], and get a lot of attention despite including nonscientific content.

Political issues and sanctions