Tanzania Journal of Health Research Journal / Tanzania Journal of Health Research / About the Journal (function() { function async_load(){ var s = document.createElement('script'); s.type = 'text/javascript'; s.async = true; var theUrl = 'https://www.journalquality.info/journalquality/ratings/2411-www-ajol-info-thrb'; s.src = theUrl + ( theUrl.indexOf("?") >= 0 ? "&" : "?") + 'ref=' + encodeURIComponent(window.location.href); var embedder = document.getElementById('jpps-embedder-ajol-thrb'); embedder.parentNode.insertBefore(s, embedder); } if (window.attachEvent) window.attachEvent('onload', async_load); else window.addEventListener('load', async_load, false); })();

Tanzania Journal of Health Research (TJHR) was established 1997 as Tanzania Health Research Bulletin. It is a peer-reviewed journal open to national and international community contributions. By adopting an Open Access policy, the Journal enables the unrestricted access and reuse of all peer-reviewed published research findings. The National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania publishes it four times yearly (January, April, July, and October).

TJHR publishes original articles that cover issues related to epidemiology and public health. These include, but are not limited to, social determinants of health, the structural, biomedical, environmental, behavioural, and occupational correlates of health and diseases, and the impact of health policies, practices, and interventions on the community.

It accepts articles written in English; spelling should be based on British English. Manuscripts should be prepared by the fifth edition of the “Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals” established by the Vancouver Group (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, ICMJE). For additional details not covered in the ICMJE Recommendations, TJHR refers to the American Medical Association (AMA) Manual of Style (10th edition), published by the American Medical Association and Oxford University Press.

TJHR is committed to information sharing and transparency with a mission of promoting the Essential National Health Research Initiative in Tanzania and particular demand-driven health research. The journal targets readers interested in health research issues, non-specialist scientists, policy and decision-makers, and the general public. TJHR receives articles on various areas. Among these are Global health and human rights, environmental health, public health informatics, chronic disease epidemiology, social determinants of health, dental public health, digital health, occupational health, mental health, epidemiology, maternal and child health, health policies, systems and management, biostatistics and methods, health economics and outcomes research, health behaviour, health promotion and communication.

TJHR does not limit the length of papers submitted explicitly but encourages authors to be concise to reach our audience effectively. In some cases, providing more detail in appendices may be appropriate. Formatting approaches such as subheadings, lists, tables, figures, and highlighting key concepts are highly encouraged. Summaries and single-sentence tag lines or headlines— abstracted sentences containing keywords that convey the essential messages—are also standard. The authors must sign and submit a declaration of the copyright agreement. Original scientific articles should follow the conventional structure: Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results and Discussion.

Peer-reviewers Policy

Once manuscripts have been submitted to the TJHR, they undergo internal screening by the journal editorial team. Manuscripts meeting submission criteria and standards are thereafter assigned to three peer reviewers who are given a maximum of three weeks to undertake the review and submit reviewers’ comments.

Authors are henceforth allocated a maximum of fourteen days to respond to reviewers' comments. However, Such an allocated time may be extended upon substantive request from the authors. This turnaround time can be extended upon request from reviewers/authors. The Editor-in-Chief reviews the author's responses to ensure that the author has adequately responded to all comments raised by peer reviewers. Reviewers are then informed of the status of the manuscripts they have reviewed.

Special issues

All articles submitted are peer-reviewed in line with the journal’s standard peer-review policy and are subject to all of the journal’s standard editorial and publishing policies. This includes the journal’s policy on competing interests. The Editors declare no competing interests with the submissions they have handled through the peer review.

Editorial Policies: All manuscripts submitted to the Tanzania Journal of Health Research should adhere to the TJHR format and guidelines

Appeals and complaints: Authors who wish to appeal a rejection or make a complaint should contact the Editor-In-Chief using the corresponding email address and not otherwise.

Conflict of Interest: All authors must complete the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. You do not need to submit the forms to the Journal. Instead, the corresponding author should keep the forms on file if a question arises about competing interests related to your submission. However, the online submission system will ask you to declare any competing interests for all authors based on the ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form. If there are no competing interests, please indicate, “None declared.”

Benefits of publishing with TJHR: TJHR's open access policy allows maximum visibility of articles published in the journal as they are available to a broad community.

For further information about publishing in the Tanzania Journal of Health Research, don't hesitate to contact us at [email protected] .

Current Issue: Vol. 25 No. 4 (2024): Tanzania Journal of Health Research

Published: 2024-09-27

Original Article

Needs for establishment and adoption of regional one health approach for preparedness and response to public health threats in the east african community, impact of interventions on mosquitoes resting behaviour and species composition in lugeye village in magu district, northwestern tanzania, awareness of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension among secondary school adolescents in morogoro region, tanzania, asymptomatic bacteriuria and its determinants among pregnant women in rural southwestern nigeria, a qualitative exploration of nurses’ and midwives’ experiences in designated covid-19 healthcare facilities in rural and urban tanzania, mothers’ knowledge and practices towards pneumonia to children under five years of age in makambako town-njombe, secondary school food environment and purchase choices of adolescents in mbeya city, antibacterial activity and synergism of sapium ellipticum (hochst.) pax and harungana madagascariensis (lam. ex poir) stem bark extract against methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureusarscariensis (lam. ex poir) stem bark extracts against methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus, indonesia measles immunization program monitoring: an analysis of 5 years measles surveillance data, factors related to attitude-associated stigma among caregivers of mentally ill patients in tanzania, barriers to hiv prevention among adolescents in njombe, tanzania: knowledge gaps and accessibility of sexual and reproductive health services, understanding practice and associated factors of implementers on fidelity implementation of prime vendor system: a case study of tanzania mainland, perceived covid-19 vaccine uptake and effect on delivery of health services in tanzania: a qualitative study of community and health workers.

Clinical Presentation and Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients Supplemented with Approved Herbal Preparations in Tanzania: A Cohort Study

Role of community health workers in early detection, reporting and response to infectious disease outbreaks: experience from marburg outbreak management in kagera region, northwestern tanzania, missed advanced abdominal pregnancy: a case report, determinants of hospital performance under variable ownership pattern: a two-stage analysis, oral prosthesis cleaning practice and oral health status of removable oral prosthesis wearers who attended kilimanjaro christian medical centre, moshi, tanzania, awareness and availability of micronutrients powders among mothers and caregivers of children aged 6 - 59 months in zanzibar city, magnitude of repeat use of emergency contraceptives among women of reproductive age in tanzania, prevalence and risk factors for depression among patients with spinal cord injury attended at kilimanjaro christian medical centre from august 2021 to may 2022, effectiveness of a preoperative checklist in reducing surgery cancellations in a tertiary hospital in a low-income country, review article, socio-cultural and religious factors influencing menstrual hygiene management among schoolgirls in tanzania: a literature survey, review on genetic insights into abnormal uterine bleeding and leiomyoma developmentment.

AJOL is a Non Profit Organisation that cannot function without donations. AJOL and the millions of African and international researchers who rely on our free services are deeply grateful for your contribution. AJOL is annually audited and was also independently assessed in 2019 by E&Y.

Your donation is guaranteed to directly contribute to Africans sharing their research output with a global readership.

- For annual AJOL Supporter contributions, please view our Supporters page.

Journal Identifiers

Health Topics (United Republic of Tanzania)

The United Republic of Tanzania country health profiles provide an overview of the situation and trends of priority health problems and the health systems profile, including a description of institutional frameworks, trends in the national response, key issues and challenges. They promote evidence-based health policymaking through a comprehensive and rigorous analysis of the dynamics of the health situation and health system in the country.

The way the health system is financed and organized is a key determinant of population health and well-being. Health financing has become a central issue in Tanzania as the government seeks to improve its health system, with policy debates covering the questions of how funds should be raised, how they should be pooled to spread risks, and how they should be used to provide the services and programmes needed by their populations.

The level of spending is still insufficient to ensure equitable access to basic and essential health services and interventions, so the major concern is to ensure adequate mobilization and equitable resource allocation for health.

External sources have recently provided substantial increases in resources for selected health interventions, leading to increased attention focuses on how to sustain such increased expenditure over time. Health costs have been rising rapidly and a dominant concern is to make tough priorities in health spending at the same time reduce the rate of growth of health expenditure while maintaining the quality of the health system.

The current health financing options are not effectively offering social protection. The government is concerned in ensuring that the resources available to health are used efficiently and that they are distributed equitably, yet disparities in access to services between rural and urban areas and between the sex's remains in many settings.

Health financing heavily relies on out-of-pocket payments, placing large, sometimes catastrophic, financial burdens on households who can be pushed into poverty, or further into poverty, as a result. Moreover, the need to make such payments prevents people, especially those who are poor, from obtaining necessary care.

The immunization programme in Tanzania has as its goal reduction in morbidity and mortality due to vaccine preventable diseases. The programme’s broad areas of activity are in routine immunization service delivery, disease surveillance and coordination of supplementary immunization activities.

In the recent past, Tanzania has been in a process of revitalization, with improvements in the planning process, community ownership and involvement, improving coverage, effective mobilization of funds for EPI, improvements in safety of vaccine delivery and introduction of new and under utilized vaccines. Auto Destruct syringes are now used in the programme, and the vaccine for Hepatitis B was introduced, to be delivered as a combination vaccine with DTP, in the immunization schedule since 2002.

To continue implementing its mandate IVD has assisted the EPI programme has identify strategies to undertake and fill funding gap through:

- mobilizing additional resources;

- improving the reliability of resources though ICC and Partiners; and

- improving the efficiency of the programme.

This programme supports the building up of blood transfusion services in Zanzibar, covering all components of the service, and ensuring sustainability.

The programmes for which WHO will provide support are selected every two years through consultations with the Ministry of Health. They are then incorporated into a country's biannual programme budget. WHO could provide some additional support ranging from capacity building/strengthening, to policy development in a field of health.

Activities in this area of work are being implemented within the context of the Global Primary Prevention of Substance Abuse. The main focus is on the Mental Health Policy Guidelines and support to several NGOs in the implementation of programmes on primary prevention of substance abuse.

The vision for this area of work is to support the government of Tanzania to ensure that all people have access to the essential medicines they need and can afford; that the medicines are safe, effective, and of good quality; and that the medicines are prescribed, dispensed and used rationally. It also supports the country in integrating traditional medicine into the health delivery system and for ensuring the safe practice of traditional medicine.

It aims at strengthening the pharmaceutical sector in Tanzania within the WHO`s Medicine Strategy and the Africa Region’s Intensified Essential Drugs Programme which support areas of medicine policies development, monitoring and evaluation; access; quality and safety and promotion of rational use of essential medicines. Similarly it aims at guiding the development of traditional medicine (TM) and complementary or alternative medicine in the country within the WHO Regional Traditional Medicine Strategy which has the following objectives:

- to develop a framework for integration of the positive aspects of TM into health systems and services;

- to establish mechanisms for the protection of cultural and intellectual property rights;

- to develop viable local industries to improve access to TM;

- to strengthen national capacity to mobilize stakeholders and formulate and implement relevant policies; and

- to promote the cultivation and maintenance of medicinal plants.

Health promotion is primarily a process used to address various sources of ill health especially those related to life style. In Tanzania, the focus has been in the development of the National Health Promotion Policy Guidelines and provision of technical support in health promotion, procurement and dissemination of appropriate health information, community involvement and participation, and ensuring greater involvement of other sectors in health related actions.

It also covers the promotion of policy guidelines on environmental health including promotion of the Healthy Settings Approach, food safety, chemical management and safety, occupational hygiene and safety as well as emergency preparedness and response (EPR). An achievement in this area includes having health promotion focal persons at district level in all the districts in the country to coordinate and facilitate health promotion activities at community level.

The Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in collaboration with WHO has trained first responders from different areas and has formed EPR teams in two regions prone to motor accidents.

The inclusion of Making Pregnancy Safer as part of Safe Motherhood was adopted by the 49th Session of the WHO Regional Committee for Africa.

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is estimated to be 578 per 100 000 live births with about 80% of deaths occurring during childbirth and in the immediate postpartum period. The neonatal mortality rate is 32 per 1 000 live births and the infant mortality rate is estimated at 68 per 1 000 live births (Source: Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2004 - 2005).

Tanzania has developed a National Road Map Strategic Plan to accelerate reduction of maternal and newborn deaths. The Road Map provides guidance for national efforts in addressing maternal and newborn health and recognizes the existence of other strategies and initiatives with respect to reproductive and child health care. Regular monitoring of the Road Map will ensure that it is implemented towards attainment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

In Tanzania, WHO has been working in collaboration with other partners in providing a leadership role in developing standards for care and treatment of women and girls that incorporate gender equalities and equity in health delivery, and advising on functions that health facilities should perform in order to reduce risks associated with pregnancy and child birth.

Adolescents (aged 10-24 years) have very special needs and continue to face limited access to information and quality and friendly services to enable them to reach their full potential. Adolescents are also at a higher risk of acquiring sexually transmitted diseases including HIV/AIDS.

WHO assists in Tanzania to develop strategies to address the special needs for this age group in terms of knowledge and services. WHO advocates for the involvement of adolescents and parents provision of adolescent-friendly services.

This is a strategy developed by WHO and UNICEF in 1995 with the goal of contributing to the reduction of infant and childhood morbidity and mortality due to common killers of children under five years. These include malaria, diarrhoea, pneumonia, measles, malnutrition and anaemia. These are addressed in an integrated manner.

The approach aims at improving health worker's skills to manage childhood illnesses, improving health system support as well as family and community practices. WHO is providing support to the Ministry of Health and other stakeholders to introduce and scale up the approach including monitoring and evaluation of the strategy.

The WCO has been keeping this area active despite handicaps of financing. Main activities have been the collaborative venture with Tanzania Training Center for Orthopedic Technicians (TATCOT) at KCMC Kilimanjaro under USAID support which came to an end in 2006.

Gains from this collaboration have been innovations in Wheelchair Technology, motivating organization of Spinal Injured persons for self-care and affirmative action, and facilitation of TATCOT to become a WHO Collaborating Centre.

Disease reporting in Tanzania has improved steadily and the ministry of health is now reporting weekly by its 114 districts and continues to report monthly as well. Disease surveillance, reporting and responding to outbreaks is also solid.

WHO and the Ministry of Health work in a coordinated and efficient manner. WHO has also responded to MOH requests for support during outbreaks, e.g. in supply of drugs or in outbreak investigations. Other teams work in close collaboration in sharing, data, transport, assignments such as in the training where appropriate. Management of data and its use has also been given special priority.

Malaria (MAL)

Tanzania is one of the countries at the forefront of implementing the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) partnership.

WHO assists the country directly in implementing and scaling up the malaria control interventions in the areas of case management, vector control, malaria in pregnancy, malaria epidemics, and monitoring and evaluation. WHO supports the country to prepare a strategic plan, as well as relevant guidelines for different interventions.

Other support given to specific areas include: monitoring the antimalarial drugs efficacy and guiding the country in change of treatment policy for effective case management, scaling up insecticide treated net (ITN) use through cost effective approaches such as the voucher scheme for the vulnerable groups, and intermittent presumptive treatment (IPT) in pregnant women. Support in putting in place an effective monitoring system for indoor residual spraying (IRS), which is a relatively new intervention for Tanzania.

The national response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic was guided by the Ministry of Health since the advent of the epidemic in 1983 to 2001.

The HIV prevalence previously recorded as 9.9% is currently reported at 7% (Source: HIV/AIDS- Indicator Survey 2003-2004, March 2005). The cross-cutting effects of the pandemic have produced a rapidly growing orphan population. Responses to mitigate the attendant economic and social effects are piecemeal and insufficient.

With the establishment of the Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS) which is now charged with the responsibility of guiding the national multisectoral response to the epidemic, the challenge for WHO is to assist and facilitate in the definition, elaboration and implementation of a health sector HIV/AIDS response.

WHO provides the required technical assistance for developing and implementing essential packages of effective health sector HIV/AIDS interventions for the various levels of the health service delivery. WHO is an active member of HIV/AIDS Theme Group (UN), and the broader coordination mechanism that includes donors.

Tuberculosis (TB)

WHO participates in the control of tuberculosis in the country as part of a broad partnership by providing technical support. The programme faces an increase in TB case notifications mostly due to the impact of the HIV epidemic in the country.

The Tanzania TB programme is one of the best in the world, supported by several collaborating partners and is implementing the DOTS Strategy countrywide.

Communicable diseases control and prevention (CPC)

Communicable diseases continue to be a major health problem in Tanzania with very high prevalence among all the population; for schistosomiasis and helminthiasis a great majority is in children.

WHO has therefore assisted the Ministry of Health in selecting priority diseases for control and is providing technical and adequate resources in their control. The following diseases were jointly identified as priority:

- onchocerciasis

- lymphatic filariasis

- schistosomiasis and helminthiasis, and

- human African trypanosomiasis, trachoma.

WHO supports the health reform processes in the country. This area of work includes developing human resource for health (planning, fellowships, advocacy for equity of deployment and retention), supporting health systems development, especially at district level, strengthening of managerial processes in the health sector, and building partnerships.

Promoting and strengthening evidence based-medicine and health interventions including facilitating linkage to and processing designation of WHO Collaborating Centres enables the country office to access knowledge and information for sharing. Health system: evolution, key functions, main actors, goals, and principle challenges

The principle challenges facing the health system are the HIV/AIDs catastrophe, human resources insufficiency and de-motivation and insufficient funds to meet the growing burden of disease. In Zanzibar resource constraints in health (human and financial) are significant.

The Ministries of Health and Social Welfare (Mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar) have shifted emphasis from supporting curative care inclined institutions to public and community health by promoting organizations collaborating with Local Government, extended network of Public Services, NGO’s services and more recently private service providers. The Ministries are in the process of transformation from centralized pyramidal structures to decentralized, devolved managed care systems with central functions of policy guidance, regulation, oversight and support, and supervision including monitoring and evaluation.

The national Health policy of 1990 was revised in 2002, subsequently the Mainland Health Strategic plan was developed in 2003.Goals outlined in the policy include:

- Access to quality primary health care for all

- Access to quality reproductive health service for all individuals of appropriate ages

- Reduction in infant and maternal mortality rates by three quarters from current levels

- Universal access to safe water

- Life expectancy comparable to the level attained by typical middle-income countries

- Food self-sufficiency and food security

- Gender equality and empowerment of women in all health parameters.

Districts and Health Facilities are responsible for planning and management of district health care and health services respectively.

Main actors include Central Ministry of Health, President’s Office Regional Administration and Local Government, NGOs and Faith Based Organizations, Development Partners in Health both Bilateral and Multilateral.

Featured news

Featured publications.

- Open access

- Published: 16 January 2024

Quality of health service in the local government authorities in Tanzania: a perspective of the healthcare seekers from Dodoma City and Bahi District councils

- Richard F. Msacky 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 81 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1323 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Improvement and access to quality healthcare are a global agenda. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG-3) is committed to ensuring good health and well-being of the people by 2030. However, this commitment heavily depends on joint efforts by local authorities and the immediate service providers to communities. This paper is set to inform the status of health service provision in local authorities in Tanzania using the determinants for quality health services in Dodoma City and Bahi District.

A cross-sectional research design was employed to collect data from 400 households in the Local Government Authorities. The five-service quality (SERVQUAL) dimensions of Parasuraman were adopted to gauge the quality of service in public healthcare facilities. Descriptive statistics were used to compute the frequency and mean of the demographic information and the quality of health services, respectively. A binary logistic regression model was used to establish the influence of the demographic dimensions on the quality of health services.

The findings revealed that quality health services have not been realised for healthcare seekers. Further, the area of residence, education, and occupation are significantly associated with the perceived quality of health service delivery in the Local Government Authorities.

The healthcare facilities under the LGAs offer services whose quality is below the healthcare seekers’ expectations. The study recommends that the Local Government Authorities in Tanzania strengthen the monitoring and evaluation of health service delivery in public healthcare facilities.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The need for quality service in the health sector has been the focus of global reforms and initiatives to attain Universal Health Coverage [ 1 , 2 ]. The quality of health service delivery is salient to the satisfaction of the healthcare seekers with the services, utilization of the healthcare facilities, and healthcare performance [ 3 , 4 ]. Similarly, in Local Government Authorities (LGAs), quality health service delivery creates trust and ownership by the community members of the health service in public healthcare facilities [ 5 ]. The public sector’s desire for quality service delivery emerges with the rise of people’s living standards, technology, and awareness that oblige policymakers and decision-makers to shift their focus toward quality services rather than larger quantities of low-quality services [ 6 ]. It is equally important to note that the quality of service is a matter of concern in the health sector since negligence in improving healthcare service may cause serious outcomes, including an increase in mortality rate, dissatisfaction with healthcare services, and the community members may reject to utilize the public healthcare services [ 4 , 7 ]. Thus, countries worldwide, both developing and developed countries, are striving jointly to build health systems to attain quality [ 2 ]. The attainment of global development programs, such as SDG-3, which focuses on ensuring good healthcare and well-being of the people by 2030, depends on the quality of services provided by the healthcare facilities [ 8 ] under the Local Government Authorities.

To attain quality health service delivery, countries worldwide in the 1980s embarked on reforms that decentralized the service delivery to semi-autonomous institutions such as Local Government Authorities (LGAs) [ 9 ]. Similarly, the reforms aimed to provide LGAs and community members more control so they could improve access and quality of service delivery, including healthcare. The reforms also were meant to show that service delivery is planned and provided in preference to the local needs [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Thus, the reforms resulted in devolution’s decentralization as a strategy for devolving powers, resources, and decision-making to LGAs to improve the quality and governance of services [ 13 , 14 ].

Like other countries, Tanzania started to implement extensive reform programs as remedial measures for the economic crisis of the late 1970 and 1980 s [ 13 ]. The overall objective of the reforms was to ensure quality services within the priority sectors like health and ensure that services conform to the expectations of community members in service provision. The reforms, notably the Health Sector Reforms (HSR), the Local Government Reform Programme (LGRP), the Legal Sector Reform Programme (LSRP), and the Public Financial Management Reform Programme (PFMRP), decentralized service delivery to the LGAs [ 15 ].

In Tanzania, the Health Sector Reform and the Local Government Reform Programme of the 1990s greatly concerned quality service delivery in public healthcare facilities. In the governance context, the reforms were implemented in the spirit of decentralization by devolution. The decentralization by devolution involves the transfer of responsibilities and power for services to the local people to promote quality healthcare [ 14 ]. In this context, the LGAs (the city or municipality or district, ward, village, or mtaa ) have clear and legally recognized geographical boundaries over which they exercise authority and within which they can plan and make decisions on service delivery, including health in their area of jurisdiction [ 16 ]. Thus, the LGRP and HSR have greatly informed the broad policy of Tanzania Vision 2025, the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP), popularly known as MKUKUTA of 2005, and the Tanzania National Health Policy of 2007 [ 10 , 14 , 16 ].

Thus, the LGRP (1998–2008 and 2008–2014) and HSR (1994) resulted in significant organisational, managerial, and financial changes that promoted quality health service delivery in Tanzania from the preference of the healthcare seekers. The changes affected the health services provision and planning at the village, ward, district, region, and national levels. Owing to the LGRP and HSR changes, the health system in Tanzania gave healthcare seekers a more significant say in assessing and monitoring the quality of services through healthcare boards and committees [ 16 ]. The outcome of the implementation of the LGRP and HSR was assumed to be the availability of reliable services of high-quality and affordable to the people in healthcare facilities [ 17 ]. Similarly, to speed up the LGRP and HSR vision into realisation, Tanzania in 2015 adopted the Health Sector Strategic Plan IV (HSSP-IV) 2015–2020 with a famous slogan for reaching all households with quality healthcare [ 5 ]. The HSSP-IV emphasized the availability of drugs, human resources for health, medical equipment, and infrastructure in the dispensaries, health centers, and district hospitals to attain quality service delivery [ 5 , 18 ]. Both the reforms and strategic plan in Tanzania for the health sector resulted in the empowerment of the district or city council, ward council, village or mtaa council in the governance of health service delivery [ 10 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Studies on healthcare services show that quality healthcare positively impacts satisfaction with service delivery, improved maternal healthcare services, and the utilization of primary healthcare facilities [ 19 , 20 ]. In the same vein, it is indicated that health service delivery in Dodoma Region of Tanzania is challenged with inadequate human resources, a shortage of essential drugs, and insufficient healthcare facilities for quality service delivery [ 16 , 21 , 22 ]. The challenges in health service delivery tend to influence the choice of healthcare seekers to consume health service delivery based on individual characteristics such as gender, education, marital status, and occupation [ 23 ]. A growing body of literature shows that area of residence, gender, age, marital status, and education are essential in judging how consumers perceive the quality of service provided in the facilities [ 24 , 25 ].

Quality of service can be assessed using the service quality model proposed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry. The model uses five dimensions; tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy, to explain the experience of quality of service received by the beneficiary (service seeker) in the care facilities [ 26 ]. Healthcare seekers refer to the consumer and recipients of health services in a healthcare facility. The consumer and recipient proactively engage with healthcare systems and providers under the LGAs to receive necessary care, whether preventive, diagnostic, curative, or rehabilitative. Service quality assessment from the consumers’ perspective is salient as it helps the providers understand customers’ expectations, perceptions, areas for improvement, and progress made in providing quality services [ 24 , 27 ].

Similarly, healthcare seekers’ determinants of quality are essential to enable providers to segment healthcare services based on the specific needs of each group in the community. The literature on assessing service quality from consumers’ perspectives is scant in Tanzania; most of the available literature focuses on quality drawing from the experience of health workers [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Thus, this article partly addressed the gap by explaining the influence of the socio-demographic dimensions on the perceived quality of healthcare service from the experience of the healthcare seekers in the councils of Dodoma City and Bahi District in Tanzania.

Literature review

The service quality (SERVQUAL) model was developed by Parasuraman, Valerie Zeithaml, and Len Berry to measure the quality of service between 1983 and 1988. The model uses five gaps computed from the discrepancies between expectations and perceptions from five service quality dimensions [ 3 , 26 ]. The five service quality dimensions are tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [ 32 ]. Using SERVQUAL to measure customer expectations and perceptions helps identify opportunities and improve the overall service delivery outcome in the health sector (Butt & Run, 2010). Scholars have widely used the model to make inferences on service delivery quality in the education, business, and marketing sectors [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Similarly, the model in the health sector is meant to increase the methodological rigor, noting that most studies of health service delivery in the governance context from Tanzania were qualitative [ 1 , 19 , 31 , 36 ]. Thus, SERVQUAL dimensions in Table 1 were adopted and modified to determine the quality of service in the healthcare facilities from the perspective of the healthcare seekers in the LGAs of Dodoma City and Bahi District in Tanzania.

The use of the SERVQUAL model to assess the quality of health services is significant in that health services in Tanzania were reported to face several challenges [ 21 , 29 , 30 , 35 ]. However, the researchers concluded the perception and experience of the health workers [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. The quality assessment for the World Health Organisation emphasized the need for the view of healthcare seekers when assessing the service delivery for sustainability [ 37 ]. A study on the quality from the perception of the service seekers is essential as it helps the provider to understand the customer expectations, perceptions, areas for improvement, and progress made in providing quality service [ 24 , 27 ]. In addition, as the beneficiaries of care, healthcare seekers are critical stakeholders in the health system, and their feedback is necessary to develop responsive, people-centered health delivery systems under the LGAs.

Research methods and material

Study design.

This study used a cross-sectional research design. A cross-sectional design produces a snapshot of the population under the study at a particular point in time [ 38 ]. This design suit studies like this that uses the quantitative approach in the collection and analysis of data to express a relationship in a given situation. Thus, the cross-section design was adopted because the study investigated the existing situation of health services to express the relationship between demographic aspects and the quality of health service delivery. Also, this design was useful in that it could survey 400 heads of the household in time.

Settings of the study

The study was conducted in the Dodoma City and Bahi District councils, among the LGAs in Dodoma Region, Tanzania. The two councils depict urban and rural LGAs stipulated in the constitution of the United Republic of Tanzania in Article 145, that recognizes establishing the city and district in urban and rural areas to foster service delivery. The LGAs in Dodoma Region were selected because the area is among the regions in Tanzania with critical challenges of service delivery in the healthcare facilities [ 21 , 22 , 37 ]. The challenges include a high maternal mortality rate, a shortage of human resources for health, long waiting times for treatment, and inadequacy of health facilities [ 21 , 22 , 39 ]. Also, Dodoma Region is recently experiencing rapid population growth. This growth has put more pressure on service delivery, including health services. Research shows that population growth significantly impacts service delivery, specifically in healthcare [ 40 ]. The National Census of 2022 reveals a tremendous increase in population growth in Dodoma Region at the rate of 3.9% as compared to 2.3 in 2012 [ 41 , 42 ]. The rapid increase in population growth in the region is associated with the transfer of government offices from Dar-es-Salaam Region to Dodoma Region [ 22 ]. Dodoma City and Bahi District councils have many households compared to other councils in the region [ 41 ]. Thus, Dodoma City and Bahi District Councils are purposively selected to depict the councils with many households in Dodoma Region to represent urban and rural LGAs in the country. The number of households in the two councils was significant in selecting the unity of inquiry of the study.

Dodoma City has been the capital city of Tanzania since 2016 [ 22 ]. It is administratively divided into 41 wards with 170 mitaa and 39 villages. The main economic activities of people in Dodoma City are business and farming [ 21 ]. The city owns 4 health centers and 27 dispensaries for providing healthcare services to its population. It has the region’s most significant number of households. The Bahi District is among the rural council in the Dodoma Region with the highest number of households. Bahi District Council consists of 22 wards and 59 villages. The main economic activities of the people in Bahi are farming and livestock keeping. The council in its jurisdiction owns 6 health centers and 35 dispensaries [ 21 ].

Description of study participants

The data was collected from the heads of household in Dodoma City and Bahi District Councils. At the household level, the heads of the households were purposively selected as the unit of inquiry. The selection of the heads of the households as the unit of inquiry at the household level was based on the fact that, in most families, the head of the family is in-charge of all the family matters, including seeking health services. The study considered the fact that the head of the household can be a male or female from 18 years of age. The same consideration was made in the previous studies in the context of Tanzania where a person of 18 years was considered an adult person with effective social, political, and economic responsibility of influencing service delivery [ 10 , 13 , 14 ]. Thus, this study considers every healthcare seeker to be 18 years and above as an adult capable of giving information regarding their household and perceived quality. The total population of all the households in the study areas was 92,978 and 49,287 households in Dodoma City and Bahi District, respectively [ 41 ].

The study employed a statistical formula by Yamane (1967) to compute the sample size of 400, which was later proportionated to Dodoma City and Bahi District.

Where n = Sample size, N = Population size, e = The level of precision

A multi-stage technique was used to select wards, mtaa, or village and household. In the first stage, a list of wards with health centres was obtained from each council. Then, 10 wards with health centres were purposively selected, with 4 from Dodoma City and 6 from Bahi. The second selection involved randomly selecting 2 mitaa or 2 villages from each ward with the health centres. Thus, the study, in total, selected 8 mitaa and 8 villages. The third stage involved systematic sampling for selecting 400 households using a mtaa or village register obtained from the chairperson of the mtaa or village. The head or their representative was interrogated at the household level to provide demographic information and perceived healthcare quality in their village, mtaa , wards, or district. The different elements (village, mtaa , wards, or district) were selected, given the understanding that the health service delivery in the LGAs in Tanzania is organized into three levels [ 10 ]. The lowest level is the dispensary, closely monitored by the village or mtaa council. The medium level is the health centre which serves as the referral point for the dispensary and is closely monitored by the ward development committee. The last level is the city or district hospital, at the apex of health service delivery in the LGAs. Thus, the study had to consider all the wards with healthcare facilities assuming that the respondents are likely to have accessed those facilities for healthcare services.

Data collection and entry

A household survey method in a five-Likert scale questionnaire collected quantitative data from the community members who seek healthcare services in the facilities owned by the Dodoma City and Bahi District Councils. Thus, the community members are referred as health seekers given their proximity to the available dispensaries, health centers and district hospitals. The healthcare seekers were asked about demographic information and perceived healthcare quality using expectations and perceptions of the SERVQUAL dimensions: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, empathy, and assurance. The challenges of employing expectations and perceptions to assess quality in healthcare is based on the fact that recalling is not always easy and accurate, especially for a community member who visited the healthcare facility in a fragile health situation. To mitigate the challenge of administering questionnaires to ill-community members in the healthcare facility, the study, during data collection, focused on the community members with previous experience of health service delivery under the LGAs in their households. This was decided based on the assumption that all community members were once sick or had accompanied their dear ones to seek healthcare services in the healthcare facilities in their area.

Then, for the purpose of ensuring the validity of the data collection tool especially after translation of the questionnaire into Swahili language and modification of the SERVQUAL model aspects, the tool was reviewed by experts. The experts were the academic staff in the field of public health, business studies, and public administration from the University of Dodoma and the College of Business Education in Tanzania. The experts’ observation helped improve the questionnaire to ensure that it adequately measures the construct of interest. The expert review for ensuring validity was chosen given that it has the potential to identify and correct ambiguities, errors, or biases in research instruments [ 43 ].

Thus, the questionnaire captured the respondents’ demographic information, notably their area of residence, gender, age, education, marital status, and occupation. During the actual survey, the study adopted an interviewer-administered questionnaire to generate data from the respondents. The researcher or research assistant read the questionnaire in the Swahili language to the respondents, and the responses were filled in the questionnaire. Then, the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) Version 21 software was employed during data entry and analysis of the quantitative data. The interviewer-administered questionnaire method was proper, given its immediate responses and chances to give clarifications when required. While some of the respondents were from the rural community, the process also helped to do away with the challenges of reading and writing by some respondents.

Ethics consideration and informed consent

Before the survey, the research assistant was trained in data management and ethics in research.

Debriefing meetings were held each day at the end of the field to identifify difficulties and key emphasize on ethics in research work. The study obtained an approval from Dodoma Region Committee for Medical and Health Ethics. Also, the study obtained oral consent from all the respondents. The oral consent was necessary given that some respondents could not read and write as they did not attend any formal education. Similarly, the respondents were explained that they had the right to withdraw from the study in any moment.

Data analysis

The study employed a quantitative analysis technique with descriptive and inferential statistics to assess the influence of the socio-demographic dimensions on the quality of service in the health sector. Descriptive statistics were used to compute for frequency and percentages of the healthcare seekers who are consumers and beneficiaries of healthcare services in the LGAs. Similarly, descriptive statistics were used to compute the mean difference scores (P-E) between the perception and expectation dimensions of quality of service. Then, dimension scores with a positive mean difference or zero scores were labeled as high quality of service in healthcare facilities. Likewise, the dimension scores with a negative mean score were regarded as low health service quality in healthcare facilities.

Moreover, for inferential statistics, the Binary Logistic Regression Model (BLRM) was used to predict the effects of healthcare seekers’ determinants on the quality of health services in LGAs. Before the study performed BLRM, a 5 Likert scale points data on the quality of the decentralized health services were transformed into an index scale using the mean score. Later, a dummy variable of quality of service was created using the criteria that the scores greater or equal to the mean score was treated as 0 = High quality and 1 = low quality for scores below the mean. The BLRM was represented using this formula:

Where \(\pi (x)\) is the likelihood of the quality health service in the healthcare facilities, x i ’ S are set of independent variables β i ’ S represent the coefficient of a respective independent variable. The findings from the model were presented in a regression in the form of an Unadjusted Odds Ratio (UOR) and Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR). The term UOR refers to the association of individual predictors on outcome variables without the presence of other variables. The AOR refers to the association of a particular variable, an outcome variable, with the presence of other variables (controlling all other variables). Hence, both unadjusted and adjusted regression analyses were conducted. For the adjusted analysis, it is recommended that all predictors that exhibited a p -value of less than 0.2 in the unadjusted regression should be included in the model [ 44 ].

The estimated odd ratio was determined by taking the exponent of the regression parameter estimates at a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. The OR shows the increase or decrease in the likelihood of the quality of service delivery in the health facility at a given independent variable level compared to those in the reference category. The reference category was used as a benchmark to which the other group was compared.

Analysis and findings

Reliability.

Cronbach’s alpha of the five service quality dimensions with expectation and perceptions was computed to determine the internal consistency of the tool. The Cronbach’s alpha scale range from 0 to 1, with a value score above 0.7 representing an acceptable level of internal reliability [ 38 ]. As indicated in Table 2 , Cronbach’s alpha value above 0.7 indicates a high level of internal consistency for the scale.

Demographic characteristics of respondents

The demographic information captured the area of residence, gender, education, marital status, and occupation of the respondents, as presented in Table 3 . The data was captured from 400 respondents using a closed-ended questionnaire. Data revealed that 260(65%) and 140(35%) respondents were Dodoma City and Bahi District residents, respectively. The high number of respondents from Dodoma City compared to Bahi resulted from the large numbers of households in Dodoma City that influenced the sampling proportion between the two councils. The large number of households in Dodoma City can be linked to the rapid growth of the population in most cities, which is a common phenomenon in developing countries [ 42 ].

Looking at the gender of the respondents, the findings indicate that the majority of the respondents, 151(58.1%), were males from Dodoma City, and 97(69.3%) were male from Bahi District. The males were the dominant gender in this study, given that the unit of inquiry was the heads of the households. Most African families, Tanzania inclusive, are headed by a man. A woman becomes the head in the absence of the husband in the family. Data from the Tanzania Demographic Health Survey indicates that only one in four households in Tanzania is headed by a woman [ 45 ]. Thus, given the household heads distribution based on gender in Tanzania, most families in Tanzania are headed by males.

Likewise, the findings in Table 3 show that 153(58.8%) and 57(40.7%) respondents from Dodoma City and Bahi District were aged between 20 and 35 years respectively. This age size category is an active age group expected to be surrounded by several dependants to support in healthcare, including their children who are still young and elderly parents [ 14 ]. Thus, this age group has vast experience visiting healthcare facilities under the LGAs. In the same vein, Table 3 shows that the majority of the respondents 115(44.2%) Dodoma City and 99(70.7%) Bahi District] had a primary level of education as compared to 60(23.1%) and 15(10.7) respondents from Dodoma and Bahi respectively who had college level of education. The findings correspond to the Population and Household Census Report of 2022 that indicated that 83.3% of Tanzanians had primary education compared to the 2.3% who had attained college and university education [ 42 ]. The attainment of education acquired by the respondents is expected to influence their understanding and ability to gauge the quality of health services provided in the healthcare facilities under the LGAs.

Also, the findings revealed that 203(50.7%) respondents from both Dodoma City and Bahi District were married. The results are similar to the analysis observed from the census survey report, which established that most household heads, i.e., 50.9%, in Tanzania Mainland, are in a married relationship compared to divorced 2.9% and widow 3.1% [ 45 ]. This state of marital status signifies that most respondents are health seekers with responsibilities, including healthcare for their loved ones. Moreover, the findings depict that most of the respondents, 180(45.0%), were entrepreneurs. This is evidence that most healthcare seekers in Dodoma City and Bahi have a reliable income to afford healthcare services in dispensaries, health centres, and district hospitals.

Quality of health services

The quality of health service was computed from the mean differences between service quality dimensions of perception (P) and expectation (E) (P-E) in Table 4 . Five service quality dimensions adopted from SERVQUAL were considered: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [ 26 ]. The study employed the paired t-test to assess the mean difference between the perception and expectation scores of the five service quality dimensions. Interpreting the findings in this section is done based on the set criteria; i.e., the scores dimension with a positive mean difference or zero scores indicates a high quality of health services. Similarly, the dimension score with a negative mean score depicts the low quality of health services. The mean scores for all the SERVQUAL dimensions were negative and significant (Table 4 ). This negative mean difference score implies that the expectations of healthcare seekers about the quality of healthcare services have not yet been realized. Instead, healthcare seekers experience low-quality health services in healthcare facilities. Thus, the healthcare seekers did not receive optimal care from the available health services under the LGAs.

Further analysis was carried out using binary logistic regression in Table 5 . As reported in the methodological section, the binary logistic analysis was used to assess the demographic factors associated with the perceived quality of health service delivery in the Dodoma City and Bahi District local councils. The findings show that the perceived quality of health services was significantly associated with the area of residence ( P = 0.000), education ( P = 0.008), and occupation ( P = 0.000). It was observed in Table 5 that the odds of healthcare seekers residing in Bahi had high chances of experiencing low-quality health services compared to those in Dodoma City (AOR 4.019[CI,2.099, 7.695]. Also, the healthcare seekers with secondary (AOR 1.419[CI, 0.728, 2.769] and college (AOR 3.461[CI, 1.385, 8.653] levels of education had high chances of reporting low quality of health services than those with a primary level of education. Similarly, the findings revealed that the odds of experiencing low-quality in health services were high among entrepreneurs (AOR 3.553[CI, 1.823, 6.922] and employees (AOR 1.585[CI, 0.707, 3.556] than those with farming occupations.

Discussions of the findings

This study was set to assess the influence of socio-demographic dimensions on the perceived quality of service delivery in the LGAs of Dodoma City and Bahi. The findings indicated dissatisfaction with the quality of service delivery in the LGAs. Also, the results have revealed that the area of residence, level of education, and occupations were significantly associated with the quality of health service delivery. Taking the area of residence between urban and rural, the study findings revealed that the healthcare seekers in rural councils, including Bahi District, experience more low-quality service delivery. It is noted that rural councils in Tanzania and elsewhere experience more challenges of shortage of medical equipment, drug availability, limited accessibility, shortage of staff houses, shortage of human resources for health, and lack of reliable electricity to support the provision of quality health services [ 17 , 19 , 21 , 46 ]. The highlighted challenges to attain quality call for special attention from the central government and Local Government Authorities in Tanzania to develop a strategic plan to speed up rural accessibility, electrification, and housing.

Studies show that in Tanzania, the challenges to shortage of human resources for health are noted in rural councils like Bahi and urban councils of Tanzania [ 13 , 17 , 30 , 31 , 45 ]. The shortage of human resources for health in Tanzania was 67.9% in 2007 during the launching of the Tanzania Primary Health Service Development Programme (PHSDP) [ 47 ]. The PHSDP, among other vital issues, aimed to address the crisis of human resources for health at all levels of health service delivery in the country. The shortage of human resources for health poses a significant challenge in providing quality health services, as accentuated in the Health Sector Strategic Plan IV. Healthcare seekers in rural and urban councils are also constrained by other factors such as distance to the health facilities and economic ability to afford health service delivery, especially out-of-pocket payment for health service seeking [ 48 , 49 ]. The challenges in the health sector affect the quality of health services provided.

The challenges in the health sector might be linked to the low funds allocated for improving health service quality in the LGAs. For example, in the financial year 2018/2019, the government gave 6.1% of its budget to the health sector. This budget allocation is less than the Abuja Declaration of 2001 agreement, which requires African states to allocate 15% of their national budget to the health sector [ 5 , 50 , 51 ]. Tanzania is a signatory member to this declaration, yet its budget allocation is low to achieve quality health services, as emphasized by Tanzania Health Sector Strategic Plan IV and Tanzania Development Vision 2025, as well as the international commitment, including the SDG. The Health Sector Strategic Plan IV maxim is to provide quality health services to every household in Tanzania [ 5 ].

Regarding the level of education, as reported in the findings, the healthcare seekers with secondary and college education were more likely to experience low quality in health services than those with primary education. This finding is congruent with studies conducted in Benin, Ethiopia, and Nigeria [ 52 , 53 , 54 ]. The explanation for the results might be attributed to the fact that the more a person gets educated, the more s/he becomes aware of the standards of expected quality in service delivery. It can also be linked to the fact that the more educated healthcare seekers are likely to report low quality of health service because they have been more globally exposed to the local, national, and international service delivery arena. Therefore, such exposure serves as a point of reference from which to judge the quality of services compared to the less educated healthcare seekers.

Similarly, the odds of perceived quality of health as low was higher among healthcare seekers with entrepreneurial and employment occupations than farmers. The explanation for these findings might be attributed to the income obtained from the higher-paying jobs that enable them to access advanced treatment with a shorter waiting time using health insurance. Likewise, those working in the entrepreneurial and employment sectors might have higher health literacy levels, given the nature of their work. The heightened health literacy can lead to more informed decisions and higher expectations regarding quality health services. The findings are supported by the studies conducted in Nigeria and Sweden [ 54 , 55 ].

The findings presented here should be considered alongside a few noted strengths and limitations. First, the strength of this study lies in the fact that it has the potential to assist health service providers in understanding the healthcare seekers’ expectations, perceptions, areas for improvement, and progress made in providing quality service. Likewise, the study can enable the service providers to segment and plan quality healthcare service delivery based on the significant socio-demographic factors of healthcare seekers, such as area of residence, education, and occupation. Also, this study brings to the attention of stakeholders, namely health service providers, healthcare seekers, policymakers, and government, on the quality of health service in healthcare facilities under LGAs.

Regarding the limitations, this study concentrated on the health services in the two councils of Dodoma Region, and therefore, findings may not reflect the experiences in other councils and regions in Tanzania. Again, the study did not consider the views of service providers, mainly human resources for health, who could have highlighted further issues from the providers’ point of view. Similarly, this study has employed the SERVQUAL model with five dimensions to measure the healthcare seekers’ perceived quality. Using all five dimensions might not provide the sensitivity of each dimension with the demographic characteristics. Despite the limitations, choosing two councils with rural and urban features contributed to bridging the methodological approach and empirical evidence gap.

Healthcare seekers in the study areas perceive the quality of health services offered in healthcare facilities to be below their expectations. The healthcare facilities under the LGAs offer services whose quality is below the healthcare seekers’ expectations. Further, healthcare seekers in rural councils experience more low-quality service in healthcare than their counterparts in urban councils. Based on the evidence generated in this study, the LGAs should regularly train the health service providers to equip them with more skills and competencies in segmenting health services considering the demographic dimensions. In addition, the study observed that healthcare facilities under the LGAs experience financial and human resource deficits in providing quality services; hence, the community and the government should join hands to curb the deficit. Moreover, the study recommend that future studies can assess the demographic variable with one dimension of SERVQUAL for detecting the sensitive dimension of quality healthcare. Also, the study has mainly employed quantitative analysis techniques to arrive at the conclusion. Using only one method might have overlooked the contextual information that other techniques, such as qualitative, could provide. Thus, future studies can use quantitative and qualitative approaches to understand the phenomena better.

Data Availability

The dataset is not publicly available; however, upon request the author, it will be made available. The data collection tools are also available on request.

Renggli S, Mayumana I, Charles C, Mshana C, Kessy F, Tediosi F, Aerts A. Towards improved health service quality in Tanzania: an approach to increase efficiency and effectiveness of routine supportive supervision. PLoS One. 2018;13(9).

WHO. Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018.

Google Scholar

Jonkisz A, Karniej P, Krasowska D. The servqual method as an assessment tool of the quality of medical services in selected Asian countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(13).

Lim J-S, Lim K-S, Al-Aali K, Heinrichs J, Aamir A, Qureshi M. The role of hospital service quality in developing the satisfaction of the patients and hospital performance. Manage Sci Lett. 2018;8(12):1353–62.

Article Google Scholar

URT. Health sector strategic plan IV July 2015-June 2020: reaching all household with quality health care. Dar Es Salaam: MOHSW. 2015.

Rana F, Ali A, Riaz W, Irfan A. Impact of accountability on public service delivery efficiency. J Public Value Adm Insights. 2019;2(1):7–9.

Rostami F, Jahani M, Mahmoudi G. Analysis of service quality gap between perceptions and expectations of service recipients using SERVQUAL approach in selected hospitals in Golestan Province. Iran J Health Sci. 2018;6(1):58–67.

UNECA., “Report on sustainable development goals for the Eastern Africa Subregion,“ Economic Commission for Africa, Addis Ababa. 2015.

Robinson M. Introduction: decentralising service delivery? Evidence and policy implications. Inst Dev Stud. 2007;38(1):1–6.

Kigume R, Maluka S, Kamuzora P. Decentralisation and health services in Tanzania: analysis of the decision space in planning, allocation and use of financial resources. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(2):e621–e.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Islam F, “New Public Management (NPM). A dominating paradigm in public sectors. Afr J Political Sci Int Relations. 2015;9(4):141–51.

Mills A. Decentralisation and accountability in the health sector from international perspectives: what are the choices. Public Adm Dev. 1994;14(3):281–92.

Lufunyo H. Assessment of the decentralisation effectiveness on public health service delivery in rural Tanzania: A case study of Pangani and Urambo LGAs (Doctoral thesis), Dar Es Salaam: Open University of Tanzania. 2017.

Marijani R. Community participation in the decentralised health and water services delivery in Tanzania. J Water Resour Prot. 2017;9(6):637–55.

URT. National processes, reforms and programmes implementing MKUKUTA-II, Ministry of Finance. Poverty Eradication Department, Dar Es Salaam. 2011.

Frumence G, Nyamhanga T, Mwangu M, Hurtig A. Participation in health planning in a decentralised health system from facility governing committees in the Kongwa District of Tanzania. Glob Public Health. 2014;9(10):1125–38.

Kanire G, Sarwatt A, Mfuru A. Local Government Reform Programme and health service delivery in Kasulu District, Tanzania. J Public Policy Adm Res. 2014;4(7):41–53.

Msafiri D, Katera L. Healthcare delivery environment and perfomamnce in Tanzania, Repoa. Dar-Es-Salaam. 2020.

Makuka G, Sango M, Mashambo A, Mashambo A, Msuya S, Mtweve S. Clients’ perspectives on quality of delivery services in a rural-setting in Tanzania: findings from a qualitative action-research. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6(1):60–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Agarawal V, Garnesh L. Healthcare strategies for improving service delivery at private hospitals in India. J Health Manage. 2017;19(1):159–69.

Kuwawenaruwa A, Wyss K, Wiedenmayer K. The effects of medicines availability and stock-outs on household’s utilization of healthcare services in Dodoma region, Tanzania. Health Policy Plann. 2020;35(1):323–33.

Msacky R, Kembo B, Mpuya G, Benaya R, Sikato L, Ringo L. Need assessment and available investment opportunity in the health sector: a case of Dodoma Tanzania. Bus Educ J. 2017;I(3):1–7.

Mwaseba S, Mwang’onda E, Mafuru J. Patient’s perception on factors for choice of healthcare delivery at public hospitals in Dodoma City. Cent Afr J Public Health. 2018;4(3):76–80.

Widayati M, Tamtomo D, Adriani R. Factors affecting quality of health service and patient satisfaction in community health centers in North Lampung, Sumatera. J Health Policy Manage. 2017;2(2):165–75.

Butt M, Run E. Private healthcare quality: applying a SERVQUAL model. Int J Healthc Qual Assur. 2010;23(7):658–73.

Parasuraman A, Berry L, Zeithaml V. “Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: Implication for further research.“ Journal of Marketing. 1994;58(Jan):111–124.

Tegambwage A. The relative importance of service quality dimension: an empirical study in the Tanzanian higher education industry. Int Res J Interdisciplinary Multidisciplinary. 2017;III:76–86.

Ooms G, Oirschot J, Okemo D, Reed T, Ham H. Healthcare workers’ perspectives on access to sexual and reproductive health services in the public, private and private not-for-profit sectors: insights from Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. BMC Health Services Research. 2022;22(873).

August F, Nyamhanga T, Kakoko D, Nathanaeli S, Frumence G. Perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers on accountability mechanisms for enhancing quality improvement in the delivery of maternal newborns and child health services in Mkuranga, Tanzania. Front Glob Womens Health. 2022;30(3).

Mboera L, Rumisha S, Mbata D, Mremi I, Lyimo E, Joachim C. Data utilisation and factors influencing the performance of the health management information system in Tanzania. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21(498).

Khamis K, Njau B. Health care workers’ perception about the quality of health care at the outpatient department in Mwananyamala Hospital in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2016;18(1):1–9.

Mashenene R. Effects of service quality on students’ satisfaction in Tanzania higher education. Bus Educ J. 2019;2(2):1–8.

Chacha M, Mashenene R, Dengenesa D. “Service quality and students’ satisfaction in Tanzania’s higher education: A re-examination of SERVQUAL model.“ International Review of Management and Marketing, Econjournals. 2022;12(3):18–25.

Syed A, Norita A, Avraam P. Measuring service quality and customer satisfaction of the small and medium hotel industry: lesson from United Arab Emirate. Tourism Rev. 2018;74(3):349–70.

Deshwal S. Discovering service quality in retail grocery store: a case study of Delhi. Int J Appl Res. 2016;2(1):484–6.

Amani P, Hurtig A-K, Frumence G, Kiwara A, Goicolea I, Sebastiån S. Health insurance and health system (un) responsiveness: a qualitative study with elderly in rural Tanzania. BMC Health Service Research. 2021;21(1140).

WHO., “WHO quality rights tool kit,“ WHO. Geneva. 2012.

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in education. London: Routledge; 2007.

Book Google Scholar

Mshana Z, Zilihona I, Canute H. Forgotten roles of health services provision in poor Tanzania: case of faith-based organisations’ health care facilities in Dodoma region. Sci J Public Health. 2015;3(2):210–5.

Zhao Z, Pan Y, Zhu J, Wu J, Zhu R. The impact of urbanization on the delivery of public service–related SDGs in China. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2022;80.

URT., “Basic demographic and socio-economic profile, Dodoma Region,“ National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Dar-Es-Salaam. 2016.

URT., “Population and housing census reprort 2022,“ NBS. Dodoma. 2022.

Haradhan M. Two criteria for good measurements in research: validity and reliability. Annals of Spiru Haret University. 2017;17(3):58–82.

Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley. 2002.

URT. Tanzania demographic health survey and Malaria indicators 2015/2016. Dar Es Salaam. 2016a.

Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Ekholuenetale M, Shah V, Kadio B, Udenigwe O. Urban-rural difference in satisfaction with primary healthcare services in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–9.

URT. Primary Health Services Development Programme - MMAM 2007–2017. MOHSW, Dar Es Salaam. 2007.

Nuhu S, Mbambije C, Kinamhala N. Challenges in health service delivery under public-private partnership in Tanzania: stakeholders’ views from Dar es Salaam region. BMC Health Service Research. 2020;20(765).

Kahabuka C, Moland K, Kvale G, Hinderker S. Unfulfilled expectation to service offered at primary health care facilities: experience of caretakers of under-five children in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):1–11.

URT. Financial year 2018/2019: budget volume, Dar Es Salaam. Ministry of Finance and Planning. 2019.

Tondon A, Fleisher L, Li R, Yap W. Repriotizing government spending on health: pushing an elephant up the stairs? Washington: The World Bank. 2014.

Alemu A, Walle A, Atnafu D. Quality of pediatric healthcare services and associated factors in Felege-Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, North-West Ethiopia: parental perception. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1649–58.

Israel-Aina Y, Odunvbun M, Aina-Israel O. Parental satisfaction with quality of health care of children with sickle cell Disease at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City. Journal of Community Medicine and Primary Health Care. 2017;29(2).

Saka M, Akande T, Saka A, Oloyede H. Health consumer expectations and perception of quality care services at primary health care level in Nigeria. Annals of African Medical Research. 2020;3(2).

From I, Wilde-Larsson B, Nordström G, Johansson I. Formal caregivers’ perceptions of quality of care for older people: associating factors. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(623).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper was part of my thesis for the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) award in Public Administration submitted to the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. I am grateful to all the respondents who participated in the study. I also wish to give a word of thanks to Prof. Peter Kopoka and Dr. Ajali Mustafa for supervising this work.

This research was financially supported by the College of Business Education in Tanzania as part of my PhD study program at the University of Dodoma, Tanzania.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Business Administration, College of Business Education, P.O Box 2077, Dodoma, Tanzania

Richard F. Msacky

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

R.M conceptualised the study, collected the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Richard F. Msacky .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study followed all the ethical guidelines established by the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. The permission to conduct the study was granted by Dodoma Region Committee for Medical and Health Ethics with reference number HMD/E.10/VOL.IV/857. Also, the study informed consent was obtained from every respondent during data collection. Thus, the respondents were informed of their rights to withdraw from the study whenever they wished. Similarly, the identity of the individual respondents in the presentation and discussion of the data remained undisclosed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author wishes to declare that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Msacky, R.F. Quality of health service in the local government authorities in Tanzania: a perspective of the healthcare seekers from Dodoma City and Bahi District councils. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 81 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10381-2

Download citation

Received : 10 March 2023

Accepted : 25 November 2023

Published : 16 January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-10381-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Healthcare Seekers

- Local government authorities

- Healthcare Facilities

- SERVQUAL Model

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

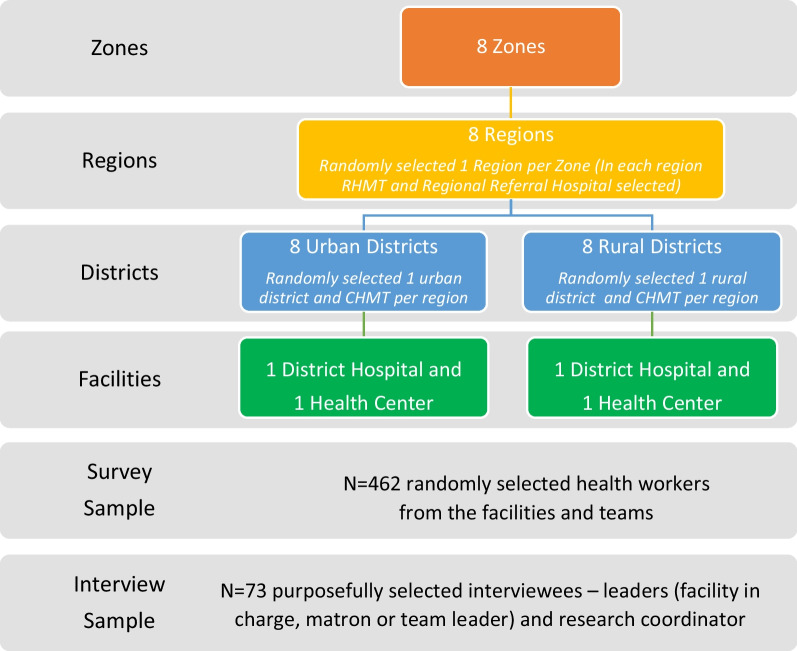

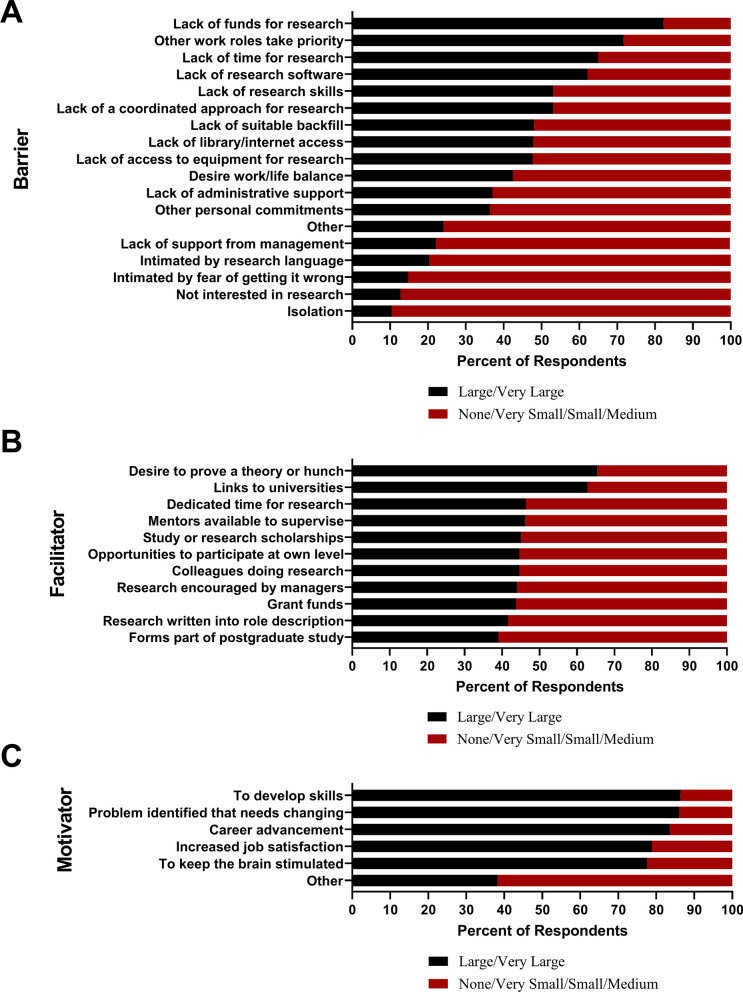

Research capacity, motivators and barriers to conducting research among healthcare providers in Tanzania’s public health system: a mixed methods study

James t kengia, albino kalolo, david barash, tuna cem hayirli, ntuli a kapologwe, ally kinyaga, john g meara, steven j staffa, noor zanial, shehnaz alidina.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2022 Nov 9; Accepted 2023 Aug 21; Collection date 2023.