Library Services

UCL LIBRARY SERVICES

- Guides and databases

- Library skills

- Systematic reviews

Formulating a research question

- What are systematic reviews?

- Types of systematic reviews

- Identifying studies

- Searching databases

- Describing and appraising studies

- Synthesis and systematic maps

- Software for systematic reviews

- Online training and support

- Live and face to face training

- Individual support

- Further help

Clarifying the review question leads to specifying what type of studies can best address that question and setting out criteria for including such studies in the review. This is often called inclusion criteria or eligibility criteria. The criteria could relate to the review topic, the research methods of the studies, specific populations, settings, date limits, geographical areas, types of interventions, or something else.

Systematic reviews address clear and answerable research questions, rather than a general topic or problem of interest. They also have clear criteria about the studies that are being used to address the research questions. This is often called inclusion criteria or eligibility criteria.

Six examples of types of question are listed below, and the examples show different questions that a review might address based on the topic of influenza vaccination. Structuring questions in this way aids thinking about the different types of research that could address each type of question. Mneumonics can help in thinking about criteria that research must fulfil to address the question. The criteria could relate to the context, research methods of the studies, specific populations, settings, date limits, geographical areas, types of interventions, or something else.

Examples of review questions

- Needs - What do people want? Example: What are the information needs of healthcare workers regarding vaccination for seasonal influenza?

- Impact or effectiveness - What is the balance of benefit and harm of a given intervention? Example: What is the effectiveness of strategies to increase vaccination coverage among healthcare workers. What is the cost effectiveness of interventions that increase immunisation coverage?

- Process or explanation - Why does it work (or not work)? How does it work (or not work)? Example: What factors are associated with uptake of vaccinations by healthcare workers? What factors are associated with inequities in vaccination among healthcare workers?

- Correlation - What relationships are seen between phenomena? Example: How does influenza vaccination of healthcare workers vary with morbidity and mortality among patients? (Note: correlation does not in itself indicate causation).

- Views / perspectives - What are people's experiences? Example: What are the views and experiences of healthcare workers regarding vaccination for seasonal influenza?

- Service implementation - What is happening? Example: What is known about the implementation and context of interventions to promote vaccination for seasonal influenza among healthcare workers?

Examples in practice : Seasonal influenza vaccination of health care workers: evidence synthesis / Loreno et al. 2017

Example of eligibility criteria

Research question: What are the views and experiences of UK healthcare workers regarding vaccination for seasonal influenza?

- Population: healthcare workers, any type, including those without direct contact with patients.

- Context: seasonal influenza vaccination for healthcare workers.

- Study design: qualitative data including interviews, focus groups, ethnographic data.

- Date of publication: all.

- Country: all UK regions.

- Studies focused on influenza vaccination for general population and pandemic influenza vaccination.

- Studies using survey data with only closed questions, studies that only report quantitative data.

Consider the research boundaries

It is important to consider the reasons that the research question is being asked. Any research question has ideological and theoretical assumptions around the meanings and processes it is focused on. A systematic review should either specify definitions and boundaries around these elements at the outset, or be clear about which elements are undefined.

For example if we are interested in the topic of homework, there are likely to be pre-conceived ideas about what is meant by 'homework'. If we want to know the impact of homework on educational attainment, we need to set boundaries on the age range of children, or how educational attainment is measured. There may also be a particular setting or contexts: type of school, country, gender, the timeframe of the literature, or the study designs of the research.

Research question: What is the impact of homework on children's educational attainment?

- Scope : Homework - Tasks set by school teachers for students to complete out of school time, in any format or setting.

- Population: children aged 5-11 years.

- Outcomes: measures of literacy or numeracy from tests administered by researchers, school or other authorities.

- Study design: Studies with a comparison control group.

- Context: OECD countries, all settings within mainstream education.

- Date Limit: 2007 onwards.

- Any context not in mainstream primary schools.

- Non-English language studies.

Mnemonics for structuring questions

Some mnemonics that sometimes help to formulate research questions, set the boundaries of question and inform a search strategy.

Intervention effects

PICO Population – Intervention– Outcome– Comparison

Variations: add T on for time, or ‘C’ for context, or S’ for study type,

Policy and management issues

ECLIPSE : Expectation – Client group – Location – Impact ‐ Professionals involved – Service

Expectation encourages reflection on what the information is needed for i.e. improvement, innovation or information. Impact looks at what you would like to achieve e.g. improve team communication .

- How CLIP became ECLIPSE: a mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information / Wildridge & Bell, 2002

Analysis tool for management and organisational strategy

PESTLE: Political – Economic – Social – Technological – Environmental ‐ Legal

An analysis tool that can be used by organizations for identifying external factors which may influence their strategic development, marketing strategies, new technologies or organisational change.

- PESTLE analysis / CIPD, 2010

Service evaluations with qualitative study designs

SPICE: Setting (context) – Perspective– Intervention – Comparison – Evaluation

Perspective relates to users or potential users. Evaluation is how you plan to measure the success of the intervention.

- Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice / Booth, 2006

Read more about some of the frameworks for constructing review questions:

- Formulating the Evidence Based Practice Question: A Review of the Frameworks / Davis, 2011

- << Previous: Stages in a systematic review

- Next: Identifying studies >>

- Last Updated: Dec 5, 2024 1:39 PM

- URL: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/systematic-reviews

University of Tasmania, Australia

Systematic reviews for health: 1. formulate the research question.

- Handbooks / Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Standards for Reporting

- Registering a Protocol

- Tools for Systematic Review

- Online Tutorials & Courses

- Books and Articles about Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal

- Library Help

- Bibliographic Databases

- Grey Literature

- Handsearching

- Citation Searching

- 1. Formulate the Research Question

- 2. Identify the Key Concepts

- 3. Develop Search Terms - Free-Text

- 4. Develop Search Terms - Controlled Vocabulary

- 5. Search Fields

- 6. Phrase Searching, Wildcards and Proximity Operators

- 7. Boolean Operators

- 8. Search Limits

- 9. Pilot Search Strategy & Monitor Its Development

- 10. Final Search Strategy

- 11. Adapt Search Syntax

- Documenting Search Strategies

- Handling Results & Storing Papers

Step 1. Formulate the Research Question

A systematic review is based on a pre-defined specific research question ( Cochrane Handbook, 1.1 ). The first step in a systematic review is to determine its focus - you should clearly frame the question(s) the review seeks to answer ( Cochrane Handbook, 2.1 ). It may take you a while to develop a good review question - it is an important step in your review. Well-formulated questions will guide many aspects of the review process, including determining eligibility criteria, searching for studies, collecting data from included studies, and presenting findings ( Cochrane Handbook, 2.1 ).

The research question should be clear and focused - not too vague, too specific or too broad.

You may like to consider some of the techniques mentioned below to help you with this process. They can be useful but are not necessary for a good search strategy.

PICO - to search for quantitative review questions

Richardson, WS, Wilson, MC, Nishikawa, J & Hayward, RS 1995, 'The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions', ACP Journal Club , vol. 123, no. 3, pp. A12-A12 .

We do not have access to this article at UTAS.

A variant of PICO is PICOS . S stands for Study designs . It establishes which study designs are appropriate for answering the question, e.g. randomised controlled trial (RCT). There is also PICO C (C for context) and PICO T (T for timeframe).

You may find this document on PICO / PIO / PEO useful:

- Framing a PICO / PIO / PEO question Developed by Teesside University

SPIDER - to search for qualitative and mixed methods research studies

Cooke, A, Smith, D & Booth, A 2012, 'Beyond pico the spider tool for qualitative evidence synthesis', Qualitative Health Research , vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1435-1443.

This article is only accessible for UTAS staff and students.

SPICE - to search for qualitative evidence

Cleyle, S & Booth, A 2006, 'Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice', Library hi tech , vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 355-368.

ECLIPSE - to search for health policy/management information

Wildridge, V & Bell, L 2002, 'How clip became eclipse: A mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information', Health Information & Libraries Journal , vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 113-115.

There are many more techniques available. See the below two guides from other universities for an extensive list:

- Models and frameworks from Scoping reviews guide, developed by James Cook University Library

- Framing a research question from Systematic review guide, developed by University of Maryland Libraries

This is the specific research question used in the example:

"Is animal-assisted therapy more effective than music therapy in managing aggressive behaviour in elderly people with dementia?"

Within this question are the four PICO concepts :

S - Study design

This is a therapy question. The best study design to answer a therapy question is a randomised controlled trial (RCT). You may decide to only include studies in the systematic review that were using a RCT, see Step 8 .

See source of example

Need More Help? Book a consultation with a Learning and Research Librarian or contact [email protected] .

- << Previous: Building Search Strategies

- Next: 2. Identify the Key Concepts >>

- Last Updated: Dec 9, 2024 1:54 PM

- URL: https://utas.libguides.com/SystematicReviews

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten Steps to Conduct a Systematic Review

Ernesto calderon martinez, jose r flores valdés, jaqueline l castillo, jennifer v castillo, ronald m blanco montecino, julio e morin jimenez, david arriaga escamilla, edna diarte.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Ernesto Calderon Martinez [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2023 Dec 31; Collection date 2023 Dec.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article introduces a concise 10-step guide tailored for researchers engaged in systematic reviews within the field of medicine and health, aligning with the imperative for evidence-based healthcare. The guide underscores the importance of integrating research evidence, clinical proficiency, and patient preferences. It emphasizes the need for precision in formulating research questions, utilizing tools such as PICO(S)(Population Intervention Comparator Outcome), PEO (Population Exposure Outcome), SPICE (setting, perspective, intervention/exposure/interest, comparison, and evaluation), and SPIDER (expectation, client group, location, impact, professionals, service and evaluation), and advocates for the validation of research ideas through preliminary investigations. The guide prioritizes transparency by recommending the documentation and registration of protocols on various platforms. It highlights the significance of a well-organized literature search, encouraging the involvement of experts to ensure a high-quality search strategy. The critical stages of screening titles and abstracts are navigated using different tools, each characterized by its specific advantages. This diverse approach aims to enhance the effectiveness of the systematic review process. In conclusion, this 10-step guide provides a practical framework for the rigorous conduct of systematic reviews in the domain of medicine and health. It addresses the unique challenges inherent in this field, emphasizing the values of transparency, precision, and ongoing efforts to improve primary research practices. The guide aims to contribute to the establishment of a robust evidence base, facilitating informed decision-making in healthcare.

Keywords: systematic review, guide, methodology, platforms, tools

Introduction

The necessity of evidence-based healthcare, which prioritizes the integration of top-tier research evidence, clinical proficiency, and patient preferences, is increasingly recognized [ 1 , 2 ]. Due to the extensive amount and varied approaches of primary research, secondary research, particularly systematic reviews, is required to consolidate and interpret this information with minimal bias [ 3 , 4 ]. Systematic reviews, structured to reduce bias in the selection, examination, and consolidation of pertinent research studies, are highly regarded in the research evidence hierarchy. The aim is to enable objective, repeatable, and transparent healthcare decisions by reducing systematic errors.

To guarantee the quality and openness of systematic reviews, protocols are formulated, registered, and published prior to the commencement of the review process. Platforms such as PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) aid in the registration of systematic review protocols, thereby enhancing transparency in the review process [ 5 ]. High-standard reviews comply with stringent peer review norms, ensuring that methodologies are revealed beforehand, thus reducing post hoc alterations for objective, repeatable, and transparent outcomes [ 6 ].

Nonetheless, the practical execution of systematic reviews, particularly in the field of medicine and health, poses difficulties for researchers. To address this, a succinct 10-step guide is offered to both seasoned and novice researchers, with the goal of improving the rigor and transparency of systematic reviews.

Technical report

Step 1: structure of your topic

When developing a research question for a systematic review or meta-analysis (SR/MA), it is essential to precisely outline the objectives of the study, taking into account potential effect modifiers. The research question should concentrate on and concisely explain the scientific elements and encapsulate the aim of the project.

Instruments such as PICO(S)(Population Intervention Comparator Outcome), PEO (Population Exposure Outcome), SPICE (setting, perspective, intervention/exposure/interest, comparison, and evaluation), and SPIDER (expectation, client group, location, impact, professionals, service and evaluation) assist in structuring research questions for evidence-based clinical practice, qualitative research, and mixed-methods research [ 7 - 9 ]. A joint strategy of employing SPIDER and PICO is suggested for exhaustive searches, subject to time and resource constraints. PICO and SPIDER are the frequently utilized tools. The selection between them is contingent on the research’s nature. The ability to frame and address research questions is crucial in evidence-based medicine. The "PICO format" extends to the "PICOTS" (Population Intervention Comparator Outcome Time Setting) (Table 1 ) design. Explicit delineation of these components is critical for systematic reviews, ensuring a balanced and pertinent research question with broad applicability.

Table 1. PICOTS format.

This table gives a breakdown of the mnemonic for the elements required to formulate an adequate research question. Utilizing this mnemonic leads to a proper and non-biased search. Examples extracted from “The use and efficacy of oral phenylephrine versus placebo on adults treating nasal congestion over the years in a systematic review” [ 10 ].

RCT, randomized control trial; PICOTS, Population Intervention Comparator Outcome Time Setting

While there are various formats like SPICE and ECLIPSE, PICO continues to be favored due to its adaptability across research designs. The research question should be stated in the introduction of a systematic review, laying the groundwork for impartial interpretations. The PICOTS template is applicable to systematic reviews that tackle a variety of research questions.

Validation of the Idea

To bolster the solidity of our research, we advocate for the execution of preliminary investigations and the validation of ideas. An initial exploration, especially in esteemed databases like PubMed, is vital. This process serves several functions, including the discovery of pertinent articles, the verification of the suggested concept, the prevention of revisiting previously explored queries, and the assurance of a sufficient collection of articles for review.

Moreover, it is crucial to concentrate on topics that tackle significant healthcare challenges, align with worldwide necessities and principles, mirror the present scientific comprehension, and comply with established review methodologies. Gaining a profound comprehension of the research field through pertinent videos and discussions is crucial for enhancing result retrieval. Overlooking this step could lead to the unfortunate unearthing of a similar study published earlier, potentially leading to the termination of our research, a scenario where precious time would be squandered on an issue already thoroughly investigated.

For example, during our initial exploration using the terms “Silymarin AND Liver Enzyme Levels” on PubMed, we discovered a systematic review and meta-analysis discussing the impact of Silymarin on liver enzyme levels in humans [ 11 ]. This discovery acts as a safety net because we will not pursue this identical idea/approach and face rejection; instead, we can rephrase a more sophisticated research question or objective, shifting the focus on evaluating different aspects of the same idea by just altering a part of the PICOTS structure. We can evaluate a different population, a different comparator, and a different outcome and arrive at a completely novel idea. This strategic method guarantees the relevance and uniqueness of our research within the scientific community.

Step 2: databases

This procedure is consistently executed concurrently. A well-orchestrated and orderly team is essential for primary tasks such as literature review, screening, and risk of bias evaluation by independent reviewers. During the study inclusion phase, if disagreements arise, the involvement of a third independent reviewer often becomes vital for resolution. The team’s composition should strive to include individuals with a variety of skills.

The intricacy of the research question and the expected number of references dictate the team’s size. The final team structure is decided after the definitive search, with the participation of independent reviewers dependent on the number of hits obtained. It is crucial to maintain a balance of expertise among team members to avoid undue influence from a specific group of experts. Importantly, a team requires a competent leader who may not necessarily be the most senior member or a professor. The leader plays a central role in coordinating the project, ensuring compliance with the study protocol, keeping all team members updated, and promoting their active involvement.

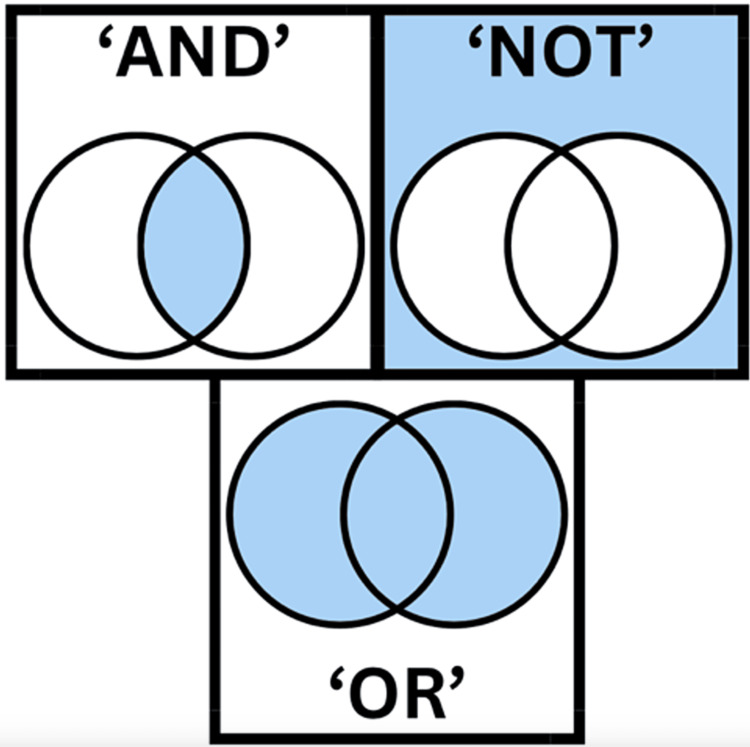

Establishing solid selection criteria is the foundational step in a systematic review. These criteria act as the guiding principles during the screening process, ensuring a focused approach that conserves time, reduces errors, and maintains transparency and reproducibility, being a primary component of all systematic review protocols. Carefully designed to align with the research question, as in Table 1 , the selection criteria cover a range of study characteristics, including design, publication date, and geographical location. Importantly, they incorporate details related to the study population, exposure and outcome measures, and methodological approaches. Concurrently, researchers must develop a comprehensive search strategy to retrieve eligible studies. A well-organized strategy using various terms and Boolean operators is typically required (Figure 1 ). It involves crafting specific search queries for different online databases, such as Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. In these searches, we can include singulars and plurals of the terms, misspellings of the terms, and related terms, among others. However, it is crucial to strike a balance, avoiding overly extensive searches that yield unnecessary results and insufficient searches that may miss relevant evidence. In this process, collaborating with a librarian or search specialist improves the quality and reproducibility of the search. For this, it is important to understand the basic characteristics of the main databases (Table 2 ). It is important for the team to include in their methodology how they will collect the data and the tools they will use for their entire protocol so that there is a consensus about this among all of them.

Table 2. Databases' main characteristics.

Principal databases where the main articles of the whole body of the research can be gathered. This is an example of specialities and it can be used for the researchers to have a variety of databases to work.

NLM, National Library of Medicine; ICTRP, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; LILACS, Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde

Figure 1. Boolean operators.

Boolean operators help break down and narrow down the search. "AND" will narrow your search so you get fewer results. It tells the database that your search results must include every one of your search terms. "OR" means MORE results. OR tells the database that you want results that mention one or both of your search terms. "NOT" means you are telling the database that you wish to have information related to the first term but not the second.

Image credits to authors of the articles (Created on www.canva.com )

Documenting and registering the protocol early in the research process is crucial for transparency and avoiding duplication. The protocol serves as recorded guidance, encompassing elements like the research question, eligibility criteria, intervention details, quality assessment, and the analysis plan. Before uploading to registry sites, such as PROSPERO, it is advisable to have the protocol reviewed by the principal investigator. The comprehensive study protocol outlines research objectives, design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, electronic search strategy, and analysis plan, providing a framework for reviewers during the screening process. These are steps previously established in our process. Registration can be done on platforms like PROSPERO 5 for health and social care reviews or Cochrane 3 for interventions.

Step 3: search

In the process of conducting a systematic review, a well-organized literature search is a pivotal step. It is suggested to incorporate at least two to four online databases, such as Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Cochrane. As mentioned earlier, formulating search strategies for each database is crucial due to their distinct requirements. In line with AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews) guidelines, a minimum of two databases should be explored in systematic reviews/meta-analyses (SR/MA), but increasing this number improves the accuracy of the results [ 22 ]. We advise including databases from China as most studies exclude databases from this demographic [ 9 ]. The choice of databases, like Cochrane or ICTRP, is dependent on the review questions, especially in the case of clinical trials. These databases cater to various health-related aspects, and researchers should select based on the research subject. Additionally, it is important to consider unique search methods for each database, as some may not support the use of Boolean operators or quotations. Detailed search strategies for each database, including customization based on specific attributes, are provided for guidance. In general, systematic reviews involve searching through multiple databases and exploring additional sources, such as reference lists, clinical trial registries, and databases of non-indexed journals, to ensure a comprehensive review of both published and, in some instances, unpublished literature.

It is important to note that the extraction of information will also vary among databases. However, our goal is to obtain a RIS, BibText, CSV, bib, or txt file to import into any of the tools we will use in subsequent steps.

Step 4: tools

It is necessary to upload all our reference files into a predetermined tool like Rayyan, Covidence, EPPI, CADIMA, and DistillerSR for the collection and management of records (Table 3 ). The subsequent step entails the elimination of duplicates using a particular method. Duplicates are recognized if they have the same title and author published in the same year or if they have the same title and author published in the same journal. Tools such as Rayyan or Covidence assist in automatically identifying duplicates. The eradication of duplicate records is vital for lessening the workload during the screening of titles and abstracts.

Table 3. Tools for title, abstract, and full-text screening.

The tools described above use artificial intelligence to help create keywords according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined previously by the researcher. This tool will help to reduce the amount of time to rule in or out efficiently.

Step 5: title and abstract screening

The process of a systematic review encompasses several steps, which include screening titles and abstracts and applying selection criteria. During the phase of title and abstract screening, a minimum of two reviewers independently evaluate the pertinence of each reference. Tools like Rayyan, Covidence, and DistillerSR are suggested for this phase due to their effectiveness. The decisions to further assess retrieved articles are made based on the selection criteria. It is recommended to involve at least three reviewers to minimize the likelihood of errors and resolve disagreements.

In the following stages of the systematic review process, the focus is on acquiring full-text articles. Numerous search engines provide links for free access to full-text articles, and in situations where this is not feasible, alternative routes such as ResearchGate are pursued for direct requests from authors. Additionally, a manual search is carried out to decrease bias, using methods like searching references from included studies, reaching out to authors and experts, and exploring related articles in PubMed and Google Scholar. This manual search is vital for identifying reports that might have been initially overlooked. The approach involves independent reviewing by assigning specific methods to each team member, with the results gathered for comparison, discussion, and minimizing bias.

Step 6: full-text screening

The second phase in the screening process is full-text screening. This involves a thorough examination of the study reports that were selected after the title and abstract screening stage. To prevent bias, it is essential that three individuals participate in the full-text screening. Two individuals will scrutinize the entire text to ensure that the initial research question is being addressed and that none of the previously determined exclusion criteria are present in the articles. They have the option to "include" or "exclude" an article. If an article is "excluded," the reviewer must provide a justification for its exclusion. The third reviewer is responsible for resolving any disagreements, which could arise if one reviewer "excludes" an article that another reviewer "includes." The articles that are "included" will be used in the systematic review.

The process of seeking additional references following the full-text screening in a systematic review involves identifying other potentially relevant studies that were not found in the initial literature search. This can be achieved by reviewing the reference lists of the studies that were included after the full-text screening. This step is crucial as it can help uncover additional studies that are relevant to your research question but might have been overlooked in the initial database search due to variations in keywords, indexing terms, or other factors [ 15 ].

A PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) chart, also referred to as a PRISMA flow diagram, is a visual tool that illustrates the steps involved in an SR/MA. These steps encompass the identification, screening, evaluation of eligibility, and inclusion of studies.

The PRISMA diagram provides a detailed overview of the information flow during the various stages of an SR/MA. It displays the count of records that were identified, included, and excluded, along with the reasons for any exclusions.

The typical stages represented on a PRISMA chart are as follows: 1) identification: this is where records are discovered through database searches. 2) screening: this stage involves going through the records after removing any duplicates. 3) eligibility: at this stage, full-text articles are evaluated for their suitability. 4) included: this refers to the studies that are incorporated into the qualitative and quantitative synthesis. The PRISMA chart serves as a valuable tool for researchers and readers alike, aiding in understanding the process of study selection in the review and the reasons for the exclusion of certain studies. It is usually the initial figure presented in the results section of your systematic review [ 4 ].

Step 7: data extraction

As the systematic review advances, the subsequent crucial steps involve data extraction from the studies included. This process involves a structured data extraction from the full texts included, guided by a pilot-tested Excel sheet, which aids two independent reviewers in meticulously extracting detailed information from each article [ 28 ]. This thorough process offers an initial comprehension of the common characteristics within the evidence body and sets the foundation for the following analytical and interpretive synthesis. The participation of two to three independent reviewers ensures a holistic approach, including the extraction of both adjusted and non-adjusted data to account for potential confounding factors in future analyses. Moreover, numerical data extracted, such as dichotomous or continuous data in intervention reviews or information on true and false results in diagnostic test reviews, undergoes a thorough process. The extracted data might be suitable for pooled analysis, depending on sufficiency and compatibility. Difficulties in harmonizing data formats might occur, and systematic review authors might resort to communication with study authors to resolve these issues and enhance the robustness of the synthesis. This multi-dimensional data extraction process ensures a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the included studies, paving the way for the subsequent analysis and synthesis phases.

Step 8: risk of bias assessment

To conduct a risk of bias in medical research, it is crucial to adhere to a specific sequence: choose tools that are specifically designed for systematic reviews. These tools should have proven acceptable validity and reliability, specifically address items related to methodological quality (internal validity), and ideally be based on empirical evidence of bias [ 29 ]. These tools should be chosen once the full text is obtained. For easy organization, it can be helpful to compile a list of the retrieved articles and view the type of study because it is necessary to understand how to select and organize each one. The most common tools to evaluate the risk of bias can be found in Table 4 .

Table 4. Tools to assess risk of bias.

The table summarizes some of the different tools to appraise the different types of studies and their main characteristics.

ROB, risk of bias; RRB, risk of reporting bias; AMSTAR; A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations; ROBINS, risk of bias in non-randomized studies; RCT, randomized controlled trials

After choosing the suitable tool for the type of study, you should know that a good risk of bias should be transparent and easily replicable. This necessitates the review protocol to include clear definitions of the biases that will be evaluated [ 30 ].

The subsequent step in determining the risk of bias is to understand the different categories of risk of bias. This will explicitly assess the risk of selection, performance, attrition, detection, and selective outcome reporting biases. It allows for separate risk of bias ratings by the outcome to account for the outcome-specific variations in detection bias and specific outcome reporting bias.

Keep in mind that assessing the risk of bias based on study design and conduct rather than reporting is very important. Poorly reported studies may be judged as unclear risk of bias. Avoid presenting the risk of bias assessment as a composite score. Finally, classifying the risk of bias as "low," "medium," or "high" is a more practical way to proceed. Methods for determining an overall categorization for the study limitations should be established a priori and documented clearly.

As a concluding statement or as a way to summarize the risk of bias, the assessment is to evaluate the internal validity of the studies included in the systematic review. This process helps to ensure that the conclusions drawn from the review are based on high-quality, reliable evidence.

Step 9: synthesis

This step can be broken down to simplify the concept of conducting a descriptive synthesis of a systematic review. 1) inclusion of studies: the final count of primary studies included in the review is established based on the screening process. 2) flowchart: the systematic review process flow is summarized in a flowchart. This includes the number of references discovered, the number of abstracts and full texts screened, and the final count of primary studies included. 3) study description: the characteristics of the included studies are detailed in a table in the main body of the manuscript. This includes the populations studied, types of exposures, intervention details, and outcomes. 4) results: if a meta-analysis is not possible, the results of the included studies are described. This includes the direction and magnitude of the effect, consistency of the effect across studies, and the strength of evidence for the effect. 5) reporting bias check: reporting bias is a systematic error that can influence the results of a systematic review. It happens when the nature and direction of the results affect the dissemination of research findings. Checking for this bias is an important part of the review process. 6) result verification: the results of the included studies should be verified for accuracy and consistency [ 36 , 37 ]. The descriptive synthesis primarily relies on words and text to summarize and explain the findings, necessitating careful planning and meticulous execution.

Step 10: manuscript

When working on a systematic review and meta-analysis for submission, it is essential to keep the bibliographic database search current if more than six to 12 months have passed since the initial search to capture newly published articles. Guidelines like PRISMA and MOOSE provide flowcharts that visually depict the reporting process for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, promoting transparency, reproducibility, and comparability across studies [ 4 , 38 ]. The submission process requires a comprehensive PRISMA or MOOSE report with these flowcharts. Moreover, consulting with subject matter experts can improve the manuscript, and their contributions should be recognized in the final publication. A last review of the results' interpretation is suggested to further enhance the quality of the publication.

The composition process is organized into four main scientific sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion, typically ending with a concluding section. After the manuscript, characteristics table, and PRISMA flow diagram are finalized, the team should forward the work to the principal investigator (PI) for comprehensive review and feedback. Finally, choosing an appropriate journal for the manuscript is vital, taking into account factors like impact factor and relevance to the discipline. Adherence to the author guidelines of journals is crucial before submitting the manuscript for publication.

The report emphasizes the increasing recognition of evidence-based healthcare, underscoring the integration of research evidence. The acknowledgment of the necessity for systematic reviews to consolidate and interpret extensive primary research aligns with the current emphasis on minimizing bias in evidence synthesis. The report highlights the role of systematic reviews in reducing systematic errors and enabling objective and transparent healthcare decisions. The detailed 10-step guide for conducting systematic reviews provides valuable insights for both experienced and novice researchers. The report emphasizes the importance of formulating precise research questions and suggests the use of tools for structuring questions in evidence-based clinical practice.

The validation of ideas through preliminary investigations is underscored, demonstrating a thorough approach to prevent redundancy in research efforts. The report provides a practical example of how an initial exploration of PubMed helped identify an existing systematic review, highlighting the importance of avoiding duplication. The systematic and well-coordinated team approach in the establishment of selection criteria, development of search strategies, and an organized methodology is evident. The detailed discussion on each step, such as data extraction, risk of bias assessment, and the importance of a descriptive synthesis, reflects a commitment to methodological rigor.

Conclusions

The systematic review process is a rigorous and methodical approach to synthesizing and evaluating existing research on a specific topic. The 10 steps we followed, from defining the research question to interpreting the results, ensured a comprehensive and unbiased review of the available literature. This process allowed us to identify key findings, recognize gaps in the current knowledge, and suggest areas for future research. Our work contributes to the evidence base in our field and can guide clinical decision-making and policy development. However, it is important to remember that systematic reviews are dependent on the quality of the original studies. Therefore, continual efforts to improve the design, reporting, and transparency of primary research are crucial.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Ernesto Calderon Martinez, Jennifer V. Castillo, Julio E. Morin Jimenez, Jaqueline L. Castillo, Edna Diarte

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Ernesto Calderon Martinez, Ronald M. Blanco Montecino , Jose R. Flores Valdés, David Arriaga Escamilla, Edna Diarte

Drafting of the manuscript: Ernesto Calderon Martinez, Julio E. Morin Jimenez, Ronald M. Blanco Montecino , Jaqueline L. Castillo, David Arriaga Escamilla

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ernesto Calderon Martinez, Jennifer V. Castillo, Jose R. Flores Valdés, Edna Diarte

Supervision: Ernesto Calderon Martinez

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

- 1. Sampieri-Cabrera R, Calderon-Martinez E. Mexico: Zenodo; 2022. Correlatos biopsicosociales en la educación médica del siglo XXI: de la teoría a la práctica. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Tenny S, Varacallo M. United States: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Evidence based medicine. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. About the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [ Dec; 2023 ]; https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/about-cdsr 8:2023. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. BMJ. 2021;372:0. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. PROSPERO. [ Dec; 2023 ]; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ 8:2023. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Training. Vol. 13. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions; p. 2023. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Bettany-Saltikov J. United Kingdom: Open University Press; 2016. How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. The use and efficacy of oral phenylephrine versus placebo treating nasal congestion over the years on adults: a systematic review. Livier Castillo J, Flores Valdés JR, Maney Orellana M, et al. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.49074. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Impact of silymarin supplements on liver enzyme levels: a systematic review. Calderon Martinez E, Herrera D, Mogan S, et al. Cureus. 2023;15:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.47608. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. Freedman SB, Adler M, Seshadri R, Powell EC. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1698–1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055119. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. MEDLINE, PubMed, and PMC (PubMed Central): How Are They Different? [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/difference.html https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/difference.html

- 14. Embase: The Medical Research Database for High-Quality, Comprehensive Evidence. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.elsevier.com/products/embase https://www.elsevier.com/products/embase

- 15. Examining Reference Lists to Find Relevant Studies for Systematic Reviews. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.cochrane.org/MR000026/METHOD_examining-reference-lists-to-find-relevant-studies-for-systematic-reviews https://www.cochrane.org/MR000026/METHOD_examining-reference-lists-to-find-relevant-studies-for-systematic-reviews

- 16. Google Scholar: Wikipedia. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Scholar https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Scholar

- 17. Web of Science: Management Library. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://johnson.library.cornell.edu/database/web-of-science/ https://johnson.library.cornell.edu/database/web-of-science/

- 18. ScienceDirect: Elsevier’s Premier Platform of Peer-Reviewed Scholarly Literature. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.elsevier.com/products/sciencedirect https://www.elsevier.com/products/sciencedirect

- 19. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform

- 20. Home: ClinicalTrials.gov. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

- 21. Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature - Wikipedia. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_American_and_Caribbean_Health_Sciences_Literature https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_American_and_Caribbean_Health_Sciences_Literature

- 22. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. BMJ. 2017;358:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Covidence: The World's #1 Systematic Review Tool. Published online. [ Dec; 2023 ]. http://2023 http://2023

- 24. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. About EPPI-Reviewer. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/About/AboutEPPIReviewer/tabid/2967/Default.aspx https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/About/AboutEPPIReviewer/tabid/2967/Default.aspx

- 26. CADIMA. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.cadima.info/ https://www.cadima.info/

- 27. Citing DistillerSR in Publications and Presentations: DistillerSR. [ Dec; 2023 ]. 2021. https://www.distillersr.com/resources/blog/citing-distillersr-in-publications-and-presentations https://www.distillersr.com/resources/blog/citing-distillersr-in-publications-and-presentations

- 28. Free Online Spreadsheet Software: Excel: Microsoft 365. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel

- 29. NA NA. Assessing the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. [ Dec; 2023 ]. 2017. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/methods . https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/methods [ PubMed ]

- 30. Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. United States: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health care interventions. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. BMJ. 2019;366:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Tools for assessing risk of reporting biases in studies and syntheses of studies: a systematic review. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Higgins JP. BMJ Open. 2018;8:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019703. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. What Is GRADE? | BMJ Best Practice. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/ https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/

- 34. Newcastle-Ottawa scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. Lo CKL, Mertz D, Loeb M. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. BMJ. 2016;355:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. Thomas J, Harden A. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. How to … synthesise qualitative data. Johnston J, Barrett A, Stenfors T. Clin Teach. 2020;17:378–381. doi: 10.1111/tct.13169. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. What you need to know about the PRISMA reporting guidelines - Covidence. [ Dec; 2023 ]. https://www.covidence.org/blog/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-prisma-reporting-guidelines/ https://www.covidence.org/blog/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-prisma-reporting-guidelines/

- View on publisher site

- PDF (285.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Developing a Research Question

_______________________________________________________________________

Watch the 4 min. video on how to frame a research question with PICO.

___ ______ ______________________________________________________________

Frameworks for research questions

Further reading:

Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 14 (1), 579.

- << Previous: Steps of a Systematic Review

- Next: Developing a Search Strategy >>

- Last Updated: Oct 9, 2024 4:00 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Non-Medical Databases

- Study Resources

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Population Health

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Give to the Library

- What is a Systematic Review?

- Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

A well-developed and answerable question is the foundation for any systematic review. This process involves:

- Systematic review questions typically follow a PICO-format (patient or population, intervention, comparison, and outcome)

- Using the PICO framework can help team members clarify and refine the scope of their question. For example, if the population is breast cancer patients, is it all breast cancer patients or just a segment of them?

- When formulating your research question, you should also consider how it could be answered. If it is not possible to answer your question (the research would be unethical, for example), you'll need to reconsider what you're asking

- Typically, systematic review protocols include a list of studies that will be included in the review. These studies, known as exemplars, guide the search development but also serve as proof of concept that your question is answerable. If you are unable to find studies to include, you may need to reconsider your question

Other Question Frameworks

PICO is a helpful framework for clinical research questions, but may not be the best for other types of research questions. Did you know there are at least 25 other question frameworks besides variations of PICO? Frameworks like PEO, SPIDER, SPICE, and ECLIPS can help you formulate a focused research question. The table and example below were created by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Libraries .

The PEO question framework is useful for qualitative research topics. PEO questions identify three concepts: population, exposure, and outcome. Research question : What are the daily living experiences of mothers with postnatal depression?

The SPIDER question framework is useful for qualitative or mixed methods research topics focused on "samples" rather than populations. SPIDER questions identify five concepts: sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type.

Research question : What are the experiences of young parents in attendance at antenatal education classes?

The SPICE question framework is useful for qualitative research topics evaluating the outcomes of a service, project, or intervention. SPICE questions identify five concepts: setting, perspective, intervention/exposure/interest, comparison, and evaluation.

Research question : For teenagers in South Carolina, what is the effect of provision of Quit Kits to support smoking cessation on number of successful attempts to give up smoking compared to no support ("cold turkey")?

The ECLIPSE framework is useful for qualitative research topics investigating the outcomes of a policy or service. ECLIPSE questions identify six concepts: expectation, client group, location, impact, professionals, and service.

Research question: How can I increase access to wireless internet for hospital patients?

- << Previous: 1. Assemble Your Team

- Next: 3. Write and Register a Protocol >>

- Last Updated: Dec 13, 2024 10:51 AM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

Teaching and Research guides

Systematic reviews.

- Introduction

- Starting the review

Develop your research question

Types of questions, pico framework, spice, spider and eclipse.

- Plan your search

- Sources to search

- Search example

- Screen and analyse

- Further help

A systematic review is an in-depth attempt to answer a specific, focused question in a methodical way.

Start with a clearly defined, researchable question , that should accurately and succinctly sum up the review's line of inquiry.

A well formulated review question will help determine your inclusion and exclusion criteria, the creation of your search strategy, the collection of data and the presentation of your findings.

It is important to ensure the question:

- relates to what you really need to know about your topic

- is answerable, specific and focused

- should strike a suitable balance between being too broad or too narrow in scope

- has been formulated with care so as to avoid missing relevant studies or collecting a potentially biased result set

Is the research question justified?

- Are healthcare providers, consumers, researchers, and policy makers requiring this evidence for their healthcare decisions?

- Is there a gap in the current literature? The question should be worthy of an answer.

- Has a similar review been done before?

Question types

To help in focusing the question and determining the most appropriate type of evidence consider the type of question. Is there is a study design (eg. Randomized Controlled Trials, Meta-Analysis) that would provide the best answer.

Is your research question to focus on:

- Diagnosis : How to select and interpret diagnostic tests

- Intervention/Therapy : How to select treatments to offer patients that do more good than harm and that are worth the efforts and costs of using them

- Prediction/Prognosis : How to estimate the patient’s likely clinical course over time and anticipate likely complications of disease

- Exploration/Etiology : How to identify causes for disease, including genetics

If appropriate, use a framework to help in the development of your research question. A framework will assist in identifying the important concepts in your question.

A good question will combine several concepts. Identifying the relevant concepts is crucial to successful development and execution of your systematic search. Your research question should provide you with a checklist for the main concepts to be included in your search strategy.

Using a framework to aid in the development of a research question can be useful. The more you understand your question the more likely you are to obtain relevant results for your review. There are a number of different frameworks available.

A technique often used in research for formulating a clinical research question is the PICO model. PICO is explored in more detail in this guide. Slightly different versions of this concept are used to search for quantitative and qualitative reviews.

For quantitative reviews-

PICO = Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

For qualitative reviews-

- Booth, A. (2006). Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library hi tech, 24(3), 355-368.

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435-1443.

- Wildridge, V., & Bell, L. (2002). How CLIP became ECLIPSE: A mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 19(2), 113-115.

- << Previous: Starting the review

- Next: Protocol >>

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2024 12:59 PM

- URL: https://rmit.libguides.com/systematicreviews

Systematic Reviews for Non-Health Sciences

- Getting started

- Types of reviews

- 0. Planning the systematic review

- 1. Formulating the research question

Formulating a research question

Purpose of a framework, selecting a framework.

- 2. Developing the protocol

- 3. Searching, screening, and selection of articles

- 4. Critical appraisal

- 5. Writing and publishing

- Guidelines & standards

- Software and tools

- Software tutorials

- Resources by discipline

- Duke Med Center Library: Systematic reviews This link opens in a new window

- Overwhelmed? General literature review guidance This link opens in a new window

Email a Librarian

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Formulating a question.

Formulating a strong research question for a systematic review can be a lengthy process. While you may have an idea about the topic you want to explore, your specific research question is what will drive your review and requires some consideration.

You will want to conduct preliminary or exploratory searches of the literature as you refine your question. In these searches you will want to:

- Determine if a systematic review has already been conducted on your topic and if so, how yours might be different, or how you might shift or narrow your anticipated focus

- Scope the literature to determine if there is enough literature on your topic to conduct a systematic review

- Identify key concepts and terminology

- Identify seminal or landmark studies

- Identify key studies that you can test your research strategy against (more on that later)

- Begin to identify databases that might be useful to your search question

Systematic review vs. other reviews

Systematic reviews required a narrow and specific research question. The goal of a systematic review is to provide an evidence synthesis of ALL research performed on one particular topic. So, your research question should be clearly answerable from the data you gather from the studies included in your review.

Ask yourself if your question even warrants a systematic review (has it been answered before?). If your question is more broad in scope or you aren't sure if it's been answered, you might look into performing a systematic map or scoping review instead.

Learn more about systematic reviews versus scoping reviews:

- CEE. (2022). Section 2:Identifying the need for evidence, determining the evidence synthesis type, and establishing a Review Team. Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. https://environmentalevidence.org/information-for-authors/2-need-for-evidence-synthesis-type-and-review-team-2/

- DistillerSR. (2022). The difference between systematic reviews and scoping reviews. DistillerSR. https://www.distillersr.com/resources/systematic-literature-reviews/the-difference-between-systematic-reviews-and-scoping-reviews

- Nalen, CZ. (2022). What is a scoping review? AJE. https://www.aje.com/arc/what-is-a-scoping-review/

- Frame your entire research process

- Determine the scope of your review

- Provide a focus for your searches

- Help you identify key concepts

- Guide the selection of your papers

There are different frameworks you can use to help structure a question.

- PICO / PECO

- What if my topic doesn't fit a framework?

The PICO or PECO framework is typically used in clinical and health sciences-related research, but it can also be adapted for other quantitative research.

P — Patient / Problem / Population

I / E — Intervention / Indicator / phenomenon of Interest / Exposure / Event

C — Comparison / Context / Control

O — Outcome

Example topic : Health impact of hazardous waste exposure

Fazzo, L., Minichilli, F., Santoro, M., Ceccarini, A., Della Seta, M., Bianchi, F., Comba, P., & Martuzzi, M. (2017). Hazardous waste and health impact: A systematic review of the scientific literature. Environmental Health , 16 (1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0311-8

The SPICE framework is useful for both qualitative and mixed-method research. It is often used in the social sciences.

S — Setting (where?)

P — Perspective (for whom?)

I — Intervention / Exposure (what?)

C — Comparison (compared with what?)

E — Evaluation (with what result?)

Learn more : Booth, A. (2006). Clear and present questions: Formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech , 24 (3), 355-368. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692127

The SPIDER framework is useful for both qualitative and mixed-method research. It is most often used in health sciences research.

S — Sample

PI — Phenomenon of Interest

D — Design

E — Evaluation

R — Study Type

Learn more : Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22 (10), 1435-1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

The CIMO framework is used to understand complex social and organizational phenomena, most useful for management and business research.

C — Context (the social and organizational setting of the phenomenon)

I — Intervention (the actions taken to address/influence the phenomenon)

M — Mechanisms (the underlying processes or mechanisms that drive change within the phenomenon)

O — Outcomes (the resulting changes that occur due to intervention/mechanisms)

Learn more : Denyer, D., Tranfield, D., & van Aken, J. E. (2008). Developing design propositions through research synthesis. Organization Studies, 29 (3), 393-413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607088020

Click here for an exhaustive list of research question frameworks from the University of Maryland Libraries.

You might find that your topic does not always fall into one of the models listed on this page. You can always modify a model to make it work for your topic, and either remove or incorporate additional elements. Be sure to document in your review the established framework that yours is based off and how it has been modified.

- << Previous: 0. Planning the systematic review

- Next: 2. Developing the protocol >>

- Last Updated: Dec 11, 2024 9:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/systematicreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Systematic Reviews

- Introduction to Systematic Reviews

- Systematic review

- Systematic literature review

- Scoping review

- Rapid evidence assessment / review

- Evidence and gap mapping exercise

- Meta-analysis

- Systematic searching for Faculty of Health students

- Systematic Reviews in Science and Engineering

- Timescales and processes

- Question frameworks (e.g PICO)

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Using grey literature

- Search Strategy This link opens in a new window

- Subject heading searching (e.g MeSH)

- Database video & help guides This link opens in a new window

- Documenting your search and results

- Data management

- How the library can help

- Systematic reviews A to Z

Using a framework to structure your research question

Your systematic review or systematic literature review will be defined by your research question. A well formulated question will help:

- Frame your entire research process

- Determine the scope of your review

- Provide a focus for your searches

- Help you identify key concepts

- Guide the selection of your papers

There are different models you can use to structure help structure a question, which will help with searching.

Selecting a framework

- What if my topic doesn't fit a framework?

A model commonly used for clinical and healthcare related questions, often, although not exclusively, used for searching for quantitively designed studies.

Example question: Does handwashing reduce hospital acquired infections in elderly people?

Richardson, W.S., Wilson, M.C, Nishikawa, J. and Hayward, R.S.A. (1995) 'The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions.' ACP Journal Club , 123(3) pp. A12

PEO is useful for qualitative research questions.

Example question: How does substance dependence addiction play a role in homelessness?

Moola S, Munn Z, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Lisy K, Tufanaru C, Qureshi R, Mattis P & Mu P. (2015) 'Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute's approach'. International Journal of Evidence - Based Healthcare, 13(3), pp. 163-9. Available at: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000064.

PCC is useful for both qualitative and quantitative (mixed methods) topics, and is commonly used in scoping reviews.

Example question: “What patient-led models of care are used to manage chronic disease in high income countries?"

Chronic disease

Patient-led care models

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

A model useful for qualitative and mixed method type research questions.

Example question: What are young parents’ experiences of attending antenatal education? (Cooke et al., 2012)

Cooke, A., Smith, D. and Booth, A. (2012) 'Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis.' Qualitative Health Research , 22(10) pp. 1435-1443

A model useful for qualitative and mixed method type research questions.

Example question: How effective is mindfulness used as a cognitive therapy in a counseling service in improving the attitudes of patients diagnosed with cancer?

Example question taken from: Tate, KJ., Newbury-Birch, D., and McGeechan, GJ. (2018) ‘A systematic review of qualitative evidence of cancer patients’ attitudes to mindfulness.’ European Journal of Cancer Care , 27(2) pp. 1 – 10.

A model useful for qualitative and mixed method type research questions, especially for question examining particular services or professions.

Example question: Cross service communication in supporting adults with learning difficulties

You might find that your topic does not always fall into one of the models listed on this page. You can always modify a model to make it work for your topic, and either remove or incorporate additional elements.

The important thing is to ensure that you have a high quality question that can be separated into its component parts.

- << Previous: Timescales and processes

- Next: Inclusion and exclusion criteria >>

- Last Updated: Dec 4, 2024 2:56 PM

- URL: https://plymouth.libguides.com/systematicreviews

- McGill Library

Systematic Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and Other Knowledge Syntheses

- Identifying the research question

- Types of knowledge syntheses

- Process of conducting a knowledge synthesis

Constructing a good research question

Inclusion/exclusion criteria, has your review already been done, where to find other reviews or syntheses, references on question formulation frameworks.

- Developing the protocol

- Database-specific operators and fields

- Search filters and tools

- Exporting and documenting search results

- Deduplicating

- Grey literature and other supplementary search methods

- Documenting the search methods

- Updating the database searches

- Resources for screening, appraisal, and synthesis

- Writing the review

- Additional training resources

Formulating a well-constructed research question is essential for a successful review. You should have a draft research question before you choose the type of knowledge synthesis that you will conduct, as the type of answers you are looking for will help guide your choice of knowledge synthesis.

Examples of systematic review and scoping review questions

- Process of formulating a question

Developing a good research question is not a straightforward process and requires engaging with the literature as you refine and rework your idea.

Some questions that might be useful to ask yourself as you are drafting your question:

- Does the question fit into the PICO question format?

- What age group?

- What type or types of conditions?

- What intervention? How else might it be described?

- What outcomes? How else might they be described?

- What is the relationship between the different elements of your question?

- Do you have several questions lumped into one? If so, should you split them into more than one review? Alternatively, do you have many questions that could be lumped into one review?

A good knowledge synthesis question will have the following qualities:

- Be focused on a specific question with a meaningful answer

- Retrieve a number of results that is manageable for the research team (is the number of results on your topic feasible for you to finish the review? Your initial literature searches should give you an idea, and a librarian can help you with understanding the size of your question).

Considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria

It is important to think about which studies will be included in your review when you are writing your research question. The Cochrane Handbook chapter (linked below) offers guidance on this aspect.

McKenzie, J. E., Brennan, S. E., Ryan, R. E., Thomson, H. J., Johnston, R. V, & Thomas, J. (2021). Chapter 3: Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. Retrieved from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-03

Once you have a reasonably well defined research question, it is important to make sure your project has not already been recently and successfully undertaken. This means it is important to find out if there are other knowledge syntheses that have been published or that are in the process of being published on your topic.

If you are submitting your review or study for funding, for example, you may want to make a good case that your review or study is needed and not duplicating work that has already been successfully and recently completed—or that is in the process of being completed. It is also important to note that what is considered “recent” will depend on your discipline and the topic.

In the context of conducting a review, even if you do find one on your topic, it may be sufficiently out of date or you may find other defendable reasons to undertake a new or updated one. In addition, looking at other knowledge syntheses published around your topic may help you refocus your question or redirect your research toward other gaps in the literature.

- PROSPERO Search PROSPERO is an international, searchable database that allows free registration of systematic reviews, rapid reviews, and umbrella reviews with a health-related outcome in health & social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice, and international development. Note: PROSPERO does not accept scoping review protocols.

- Open Science Framework (OSF) At present, OSF does not allow for Boolean searching on their site. However, you can search via https://share.osf.io/, an aggregator, that allows you to search for major keywords using Boolean and truncation. Add "review*" to your search to narrow results down to scoping, systematic, umbrella or other types of reviews. Be sure to click on the drop-down menu for "Source" and select OSF and OSF Registries (search separately as you can't combine them). This will search for ongoing and/or registered reviews in OSF.

The Cochrane Library (including systematic reviews of interventions, diagnostic studies, prognostic studies, and more) is an excellent place to start, even if Cochrane reviews are also indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed.

By default, the Cochrane Library will display “ Cochrane Reviews ” (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, aka CDSR). You can ignore the results which show up in the Trials tab when looking for systematic reviews: They are records of controlled trials.

The example shows the number of Cochrane Reviews with hiv AND circumcision in the title, abstract, or keywords.

- Google Scholar

Subject-specific databases you can search to find existing or in-process reviews